This blog started as a brief history of Innerpeffray Castle, however I came across a more intriguing story relating to the possibility that Mary Queen of Scots may have visited Innerpeffray at a particularly key time within her turbulent reign, 460 years ago this month. I thought I would explore this and try to chase the evidence and understand why she may have done so, if indeed she did visit. If you wish to trace her journey, I have provided references.

Innerpeffray Castle history background

Innerpeffray Castle was developed by James Drummond, 1st Lord Maderty in 1610, probably in place of an earlier castle previously owned by the Inchaffray Abbey. The now ruinous Castle, lying south of the Library standing on the bank of the River Earn, is a typical early 17th century tower house, on the corner of a former Roman marching camp. The design is typical of the period in Scotland with a grander, less-defensive outlook, surrounded by extensive outer courtyards and gardens.

Today the castle stands to its full height but with no roof and some collapsed walls. Getting too close or even entering the ruin would be risky.

Key references to Innerpeffray Castle history:

- canmore.org.uk/site/26040/innerpeffray-castle

- stravaiging.com/history/castle/innerpeffray-castle/

- wikipedia.org/wiki/Innerpeffray

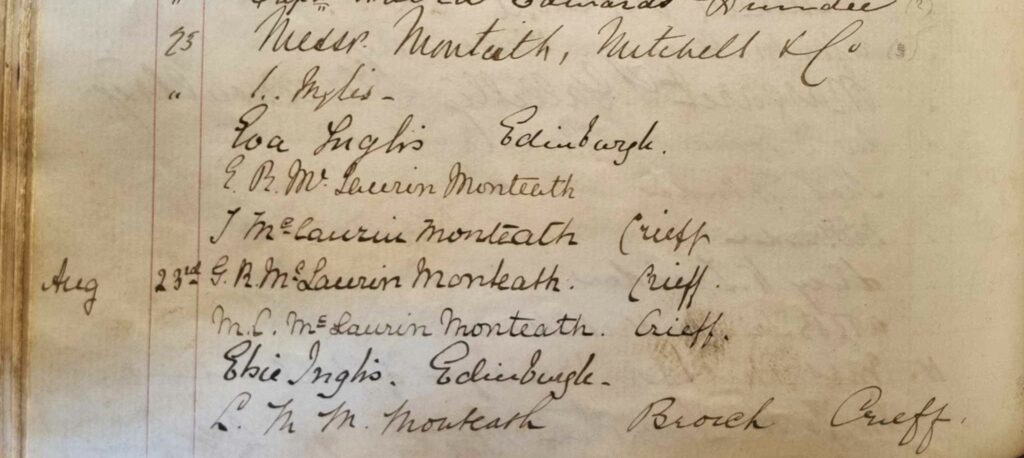

Evidence Mary may have visited the area

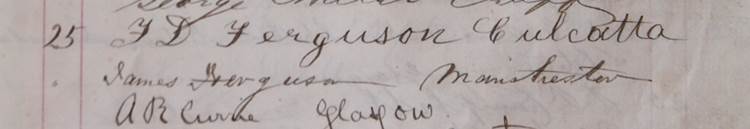

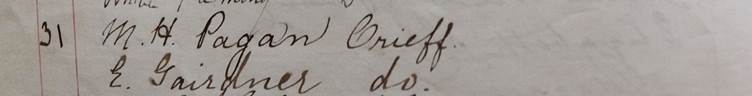

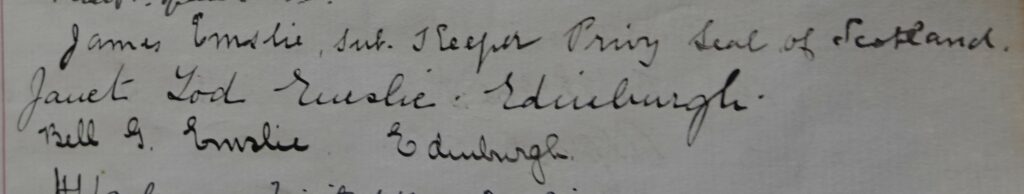

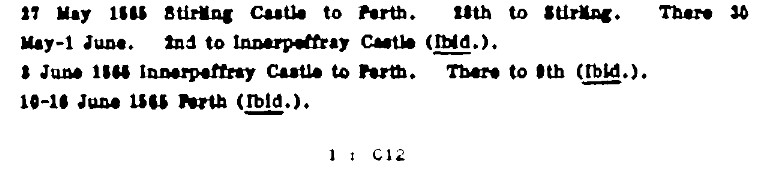

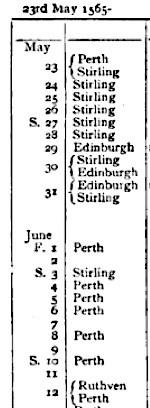

EM Furgol (1988) described Mary’s journeys across Scotland 1542-8 and 1561-8, and in 1565 he records that she stayed the night at Innerpeffray Castle on the 2nd June 1565.Furgol states that the host for the night was James Drummond of Innerpeffray, though a ‘?’ sits next to the name suggesting some uncertainty. The visit followed Mary visiting Holyrood House, Stirling Castle, Perth, then back to Stirling prior to the Innerpeffray Castle visit on the 2nd June. This suggests she reached Innerpeffray from the west, and may have crossed the River Earn at the ford below the Library. She then left Innerpeffray to return to Perth on the 3rd June, before returning to Holyrood, via Huntingtower and Dunkeld.

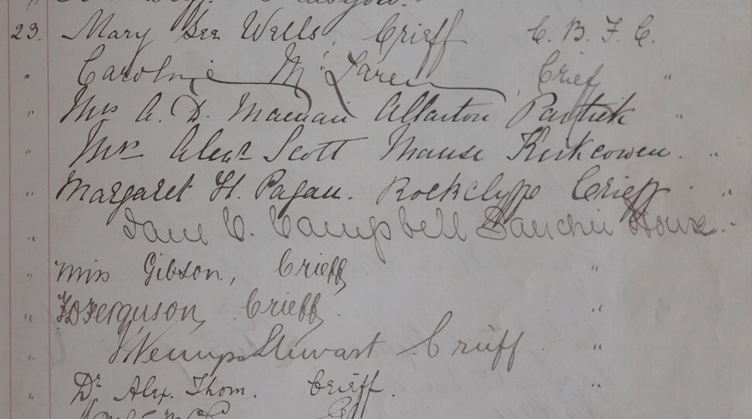

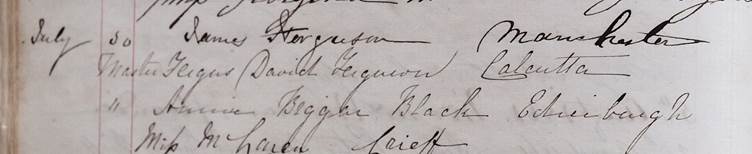

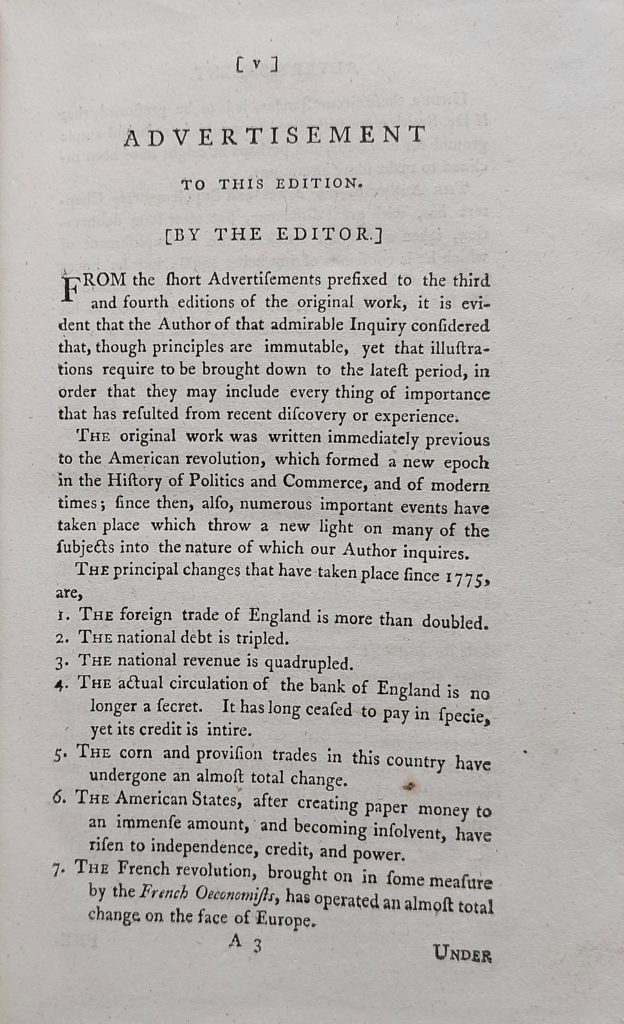

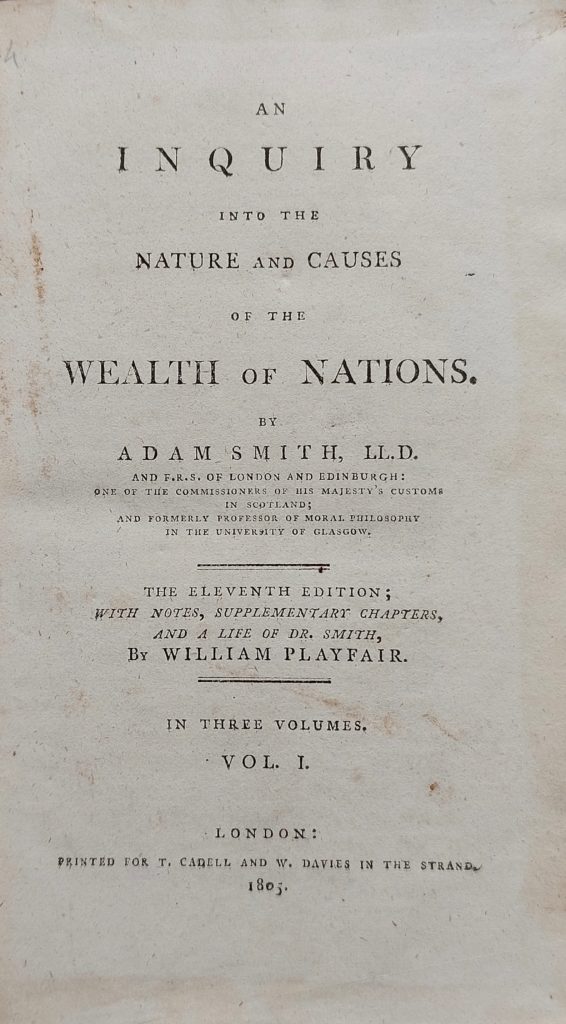

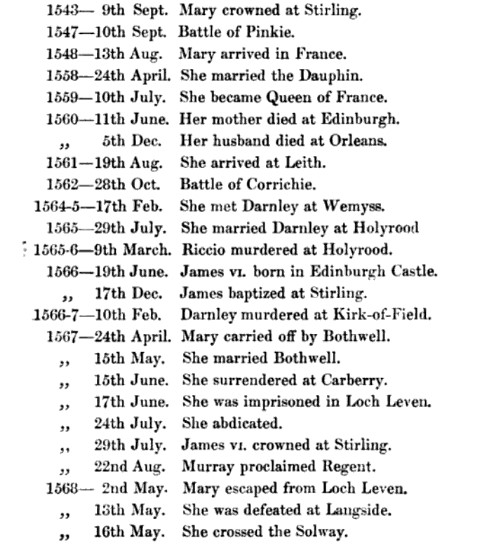

DH Fleming (1898) in ‘Mary Queen of Scots – From her birth to her flight into England’ [1] includes the following itinerary:

There is no mention of Innerpeffray though the date of the 2nd June is blank. This might be because Innerpeffray was not deemed important, compared with the other places listed. The evidence for the itinerary is the Register of Privy Seal list of letters signed by the Privy Council, however Fleming states that any reliance on their accuracy cannot be assumed as the ‘royal clerks were not always immaculate in their dates’. If Mary did visit Innerpeffray on the 2nd, Fleming suggests she came from Perth and left for Stirling, the opposite direction to that stated by Fugol.

The Marie Stuart Society website lists Mary’s progress through her kingdom and lists the following:

| Date: | From 11th May 1565 to 4th July 1565. |

| Places Visited: | Edinburgh, Stirling, Innerpeffray Abbey, Perth, Ruthven Castle, Dunkeld, Perth, Callendar House, Edinburgh. |

One wonders what ‘Innerpeffray Abbey’ is. Should Castle have been stated, rather than Abbey?

An alternative explanation is it refers to the Innerpeffray Chapel next to the library. Innerpeffray Chapel, built by the Drummonds as a private chapel in 1502, had become a collegiate community by 1542, with non-monastic clergy living on site. However, by 1565 was it a place of residence where a Queen would stay the night? It might be unlikely as the earlier castle was just down the road.

Maybe the record should have referred to Inchaffray Abbey. In medieval times, the abbey was an important religious house, however by 1561, its fortunes had declined. With the Reformation under way, Inchaffray had been turned into a secular lordship for a member of the Drummond family in 1556 and on 2 August 1565, James Drummond was given the ‘abbacy for life, i.e. possession of ‘the monastery, with its rights, fruits, tithes, lands, etc’ . James VI visited in 1601, suggesting the building, which no longer stands, could still receive significant visitors. Therefore, it could be construed that the Marie Stuart Society record points to Inchaffray Abbey, rather than Innerpeffray Abbey.

The 1565 historical context

In considering why Mary may have visited Innerpeffray, the historical context is relevant. A ‘Life and Deathline’ provided by the National Museums of Scotland sets out key activities in Mary’s life :

The visit to Innerpeffray falls between meeting Darnley in February 1565 and then marrying him in July 1565. Henry, Lord Darnley was a Catholic and was descended from both James II of Scotland and Henry VII of England.

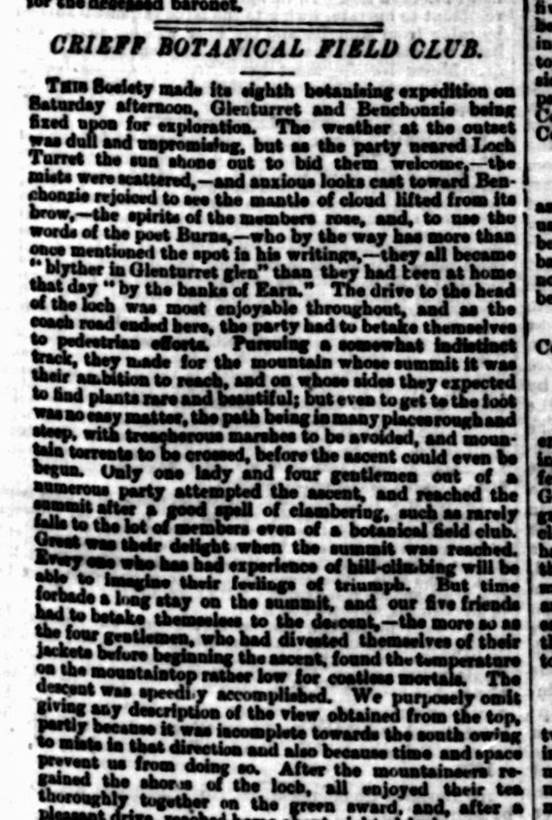

When Mary met him for the first time she thought him ‘the lustiest and best proportioned lang (tall) man she had seen’. Mary subsequently married him at Holyrood and proclaimed him King of Scots without the consent of Parliament. Opposition to Mary’s marriage arose very quickly. Her half-brother, the Protestant Earl of Moray, feared that Mary’s marriage to a Catholic threatened the Reformation, so he led an attempt to overthrow both Mary and her King Consort. The episode was more of an armed chase than an outright rebellion. The 1898 book by DH Fleming sets out the politics at the time, the part played by Queen Elizabeth of England and her agents and Mary’s decision to make Darnley her husband.

Mary’s travels around Scotland

Mary was a very busy lady during her time as Queen of Scotland, and travelled extensively through her realm. She traversed the country in order to appear at state occasions, hold judicial courts, hunt, rest from the formal atmosphere of Holyrood house, attend social events, and seek a husband. However, transportation in Scotland in the mid-16th century was underdeveloped and the absence of roads prevented coach use. Mary had to be a reasonable horsewoman to make her many cross-country journeys.

In 1565, after falling in love with and becoming engaged to Darnley, Mary undertook several journeys through the period February-July to gather support for the marriage. Such visits generally influenced her hosts in a favourable manner, as she was known to be charming. It was quite likely that Darnley was with Mary on these journeys, with the intriguing possibility that he was with her at Innerpeffray.

Why she may have visited Innerpeffray

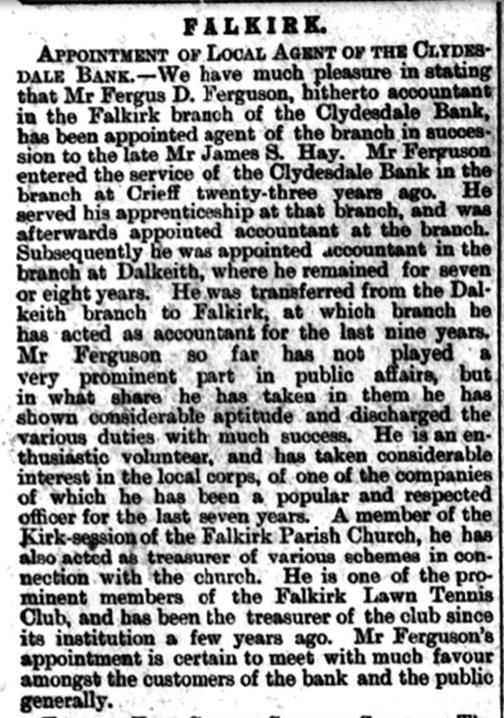

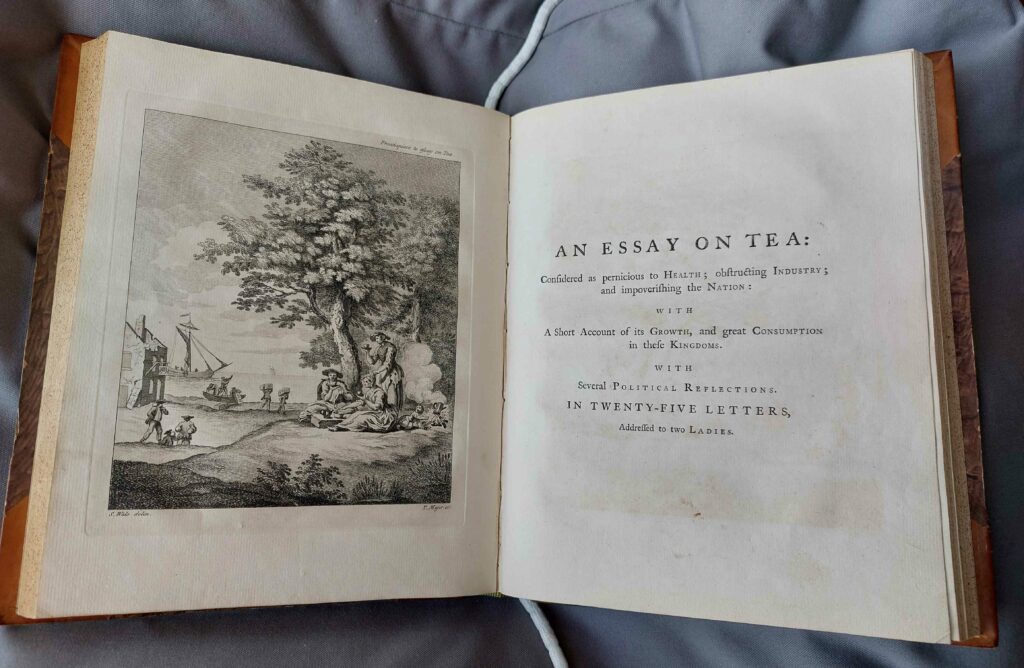

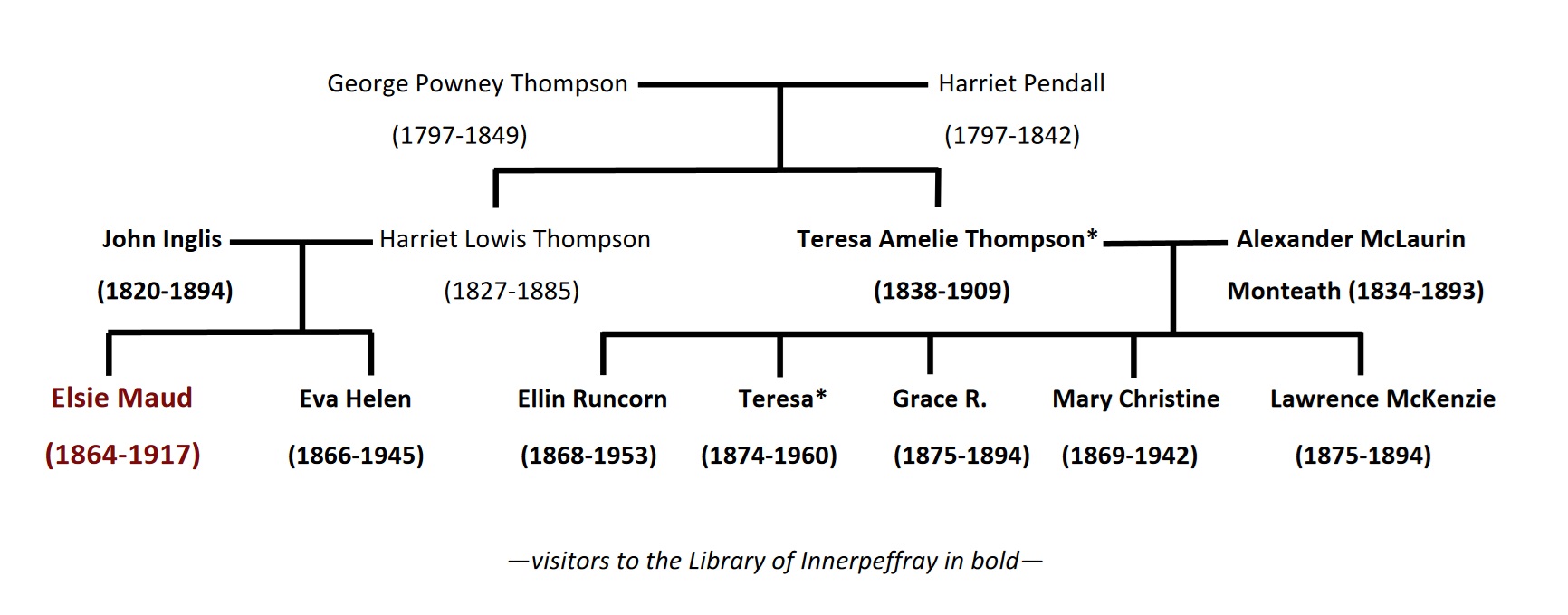

Mary travelled across Perthshire numerous times between February and July 1565 to gather support, and the support of the Drummonds and their adherents would have been key. David Drummond, 2nd Lord Drummond was a supporter of Mary Queen of Scots, known to be a Queens Man. It is noteworthy that his kinsman, John Drummond of Innerpeffray, acted as his tutor during his minority.

In the troubled years of Mary’s reign, Drummond declared for the Queen, and was an attached member of her party. His name, however, does not occur prominently in the events of the time and four years after Mary’s abdication, he died, in 1571. Whilst not a prominent adherent, it seems possible that Mary stopped overnight at Innerpeffray on the 2nd June 1565 on her way to Perth to seek Drummond’s continued support. The possibility is that Mary and Darnley met Lord Drummond and key members of his family and clan on the 2nd June to confirm their continued backing. If she had then it would be highly likely she, Darnley and her retinue would have passed the Innerpeffray Library site, up the Roman cutting below the Library and most probably entered the Drummond family chapel.

Notes and references

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Drummond-27

https://archive.org/details/cu31924092516248/page/46/mode/2up

‘The World of MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS – Progress No 6’ Marie Stuart Society website

https://www.historicenvironment.scot/visit-a-place/places/innerpeffray-chapel/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inchaffray_Abbey

Charters of Inchaffray Abbey, 1190 – 1609, National Library of Scotland https://deriv.nls.uk/dcn23/1275/3081/127530813.23.pdf

https://www.nms.ac.uk/discover-catalogue/life-and-deathline-of-mary-queen-of-scots

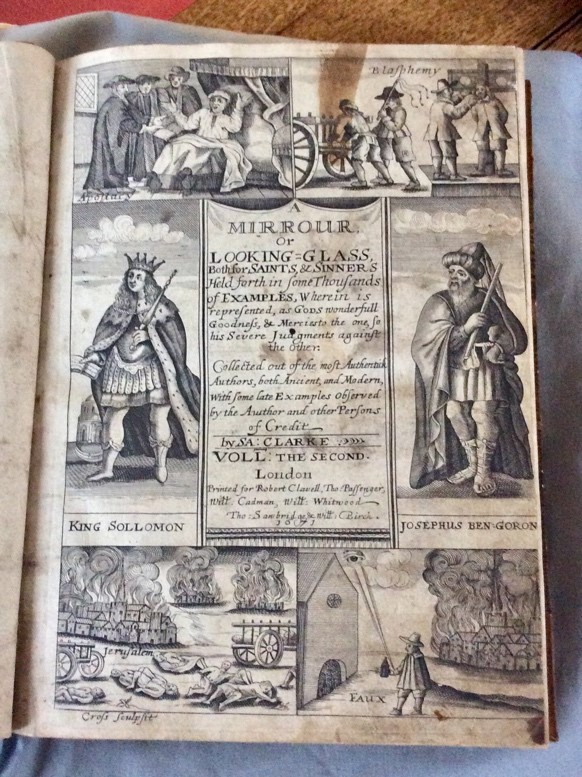

‘Mary Queen of Scots – From her birth to her flight into England’, DH Fleming 1898 (Hodder & Stoughton)

EM Furgol ‘The Scottish itinerary of Mary Queen of Scots, 1542-8 and 1561-8’, Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland Vol. 117 (1988) 1561

DG