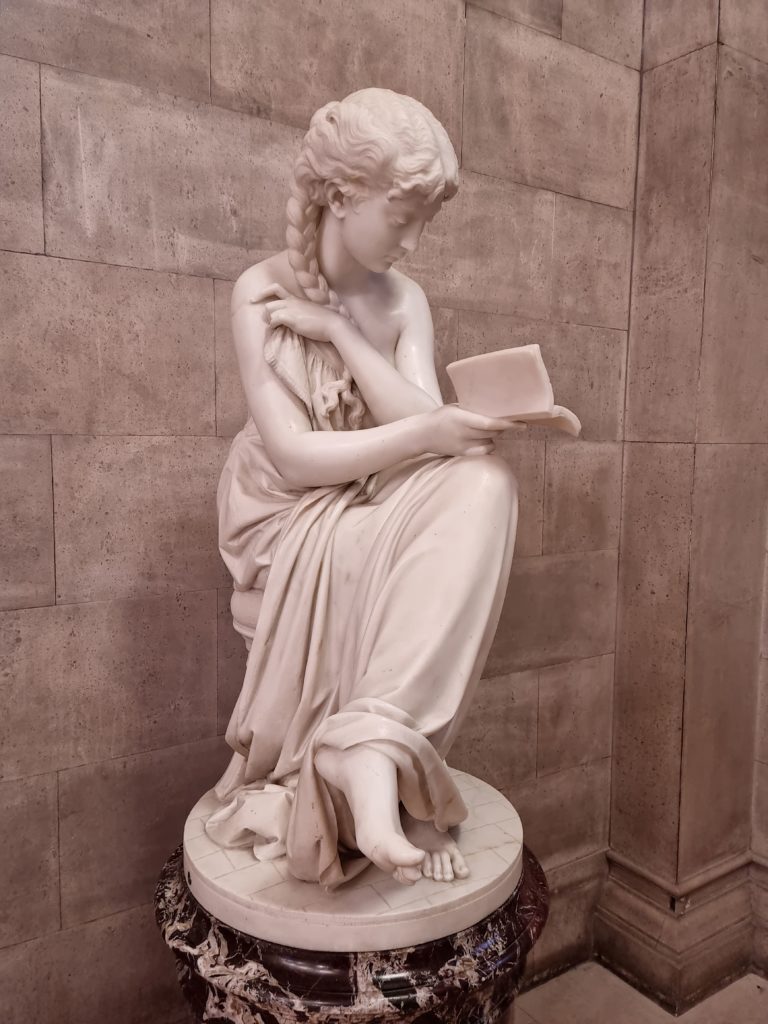

Throughout history and literature, women have been associated with the use of mirrors, both for personal reasons such as vanity and for activities that have led them into trouble e.g. witchcraft and fortune telling. Today, our homes and lifestyles are seldom without mirrors in one form or another. We use them without thinking about their history or use in past societies and we, perhaps surprisingly, still share with our children fairy tales and animated films that promote the idea of nasty queens using mirrors for their own evil purposes.

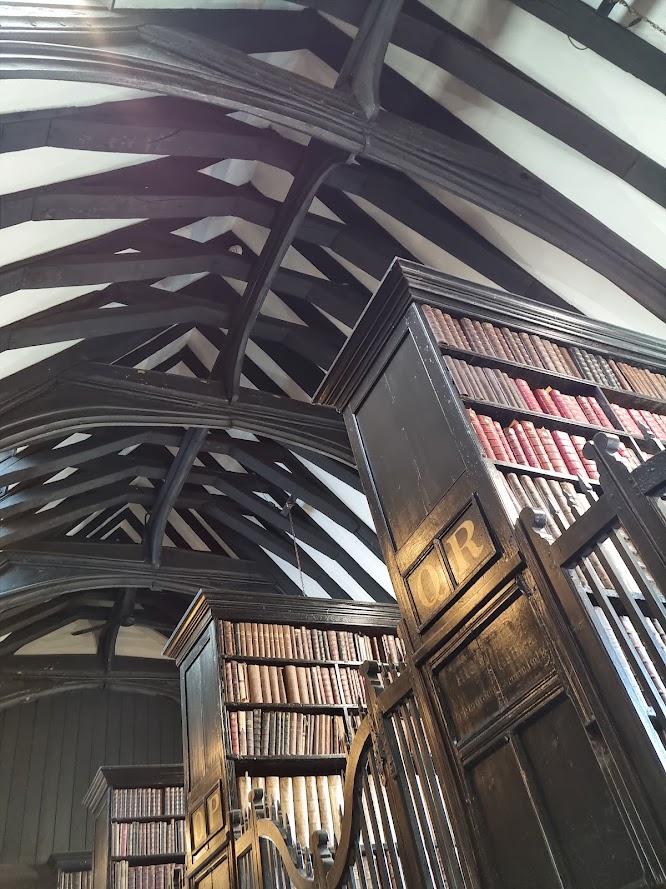

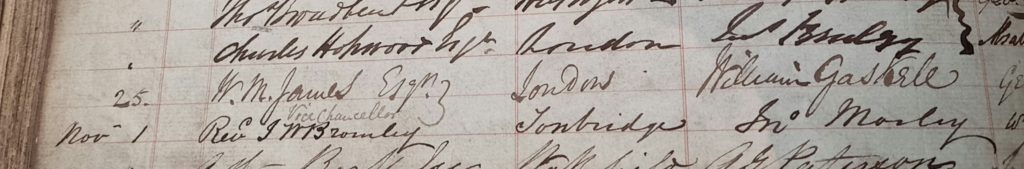

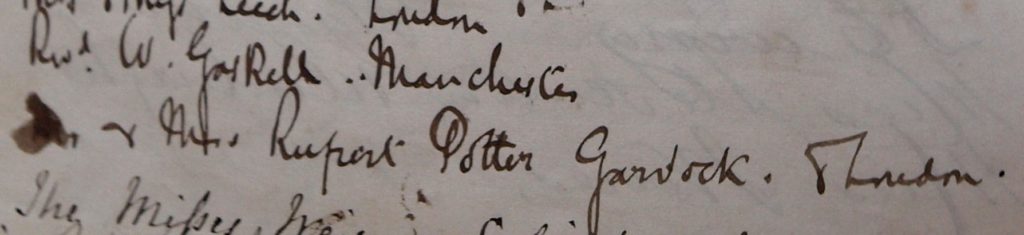

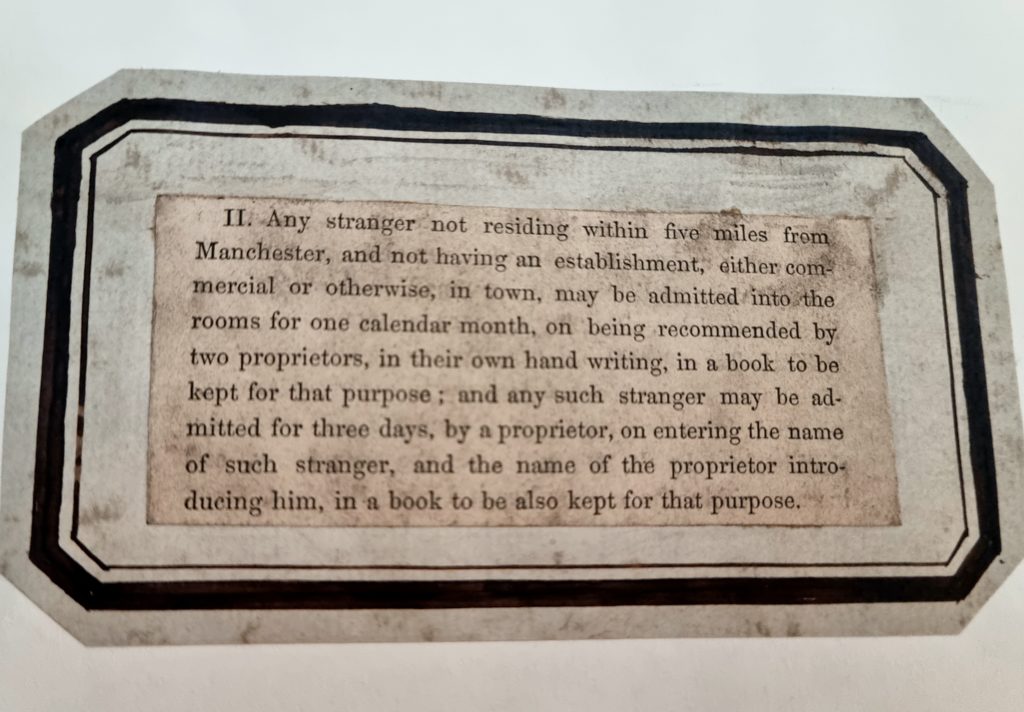

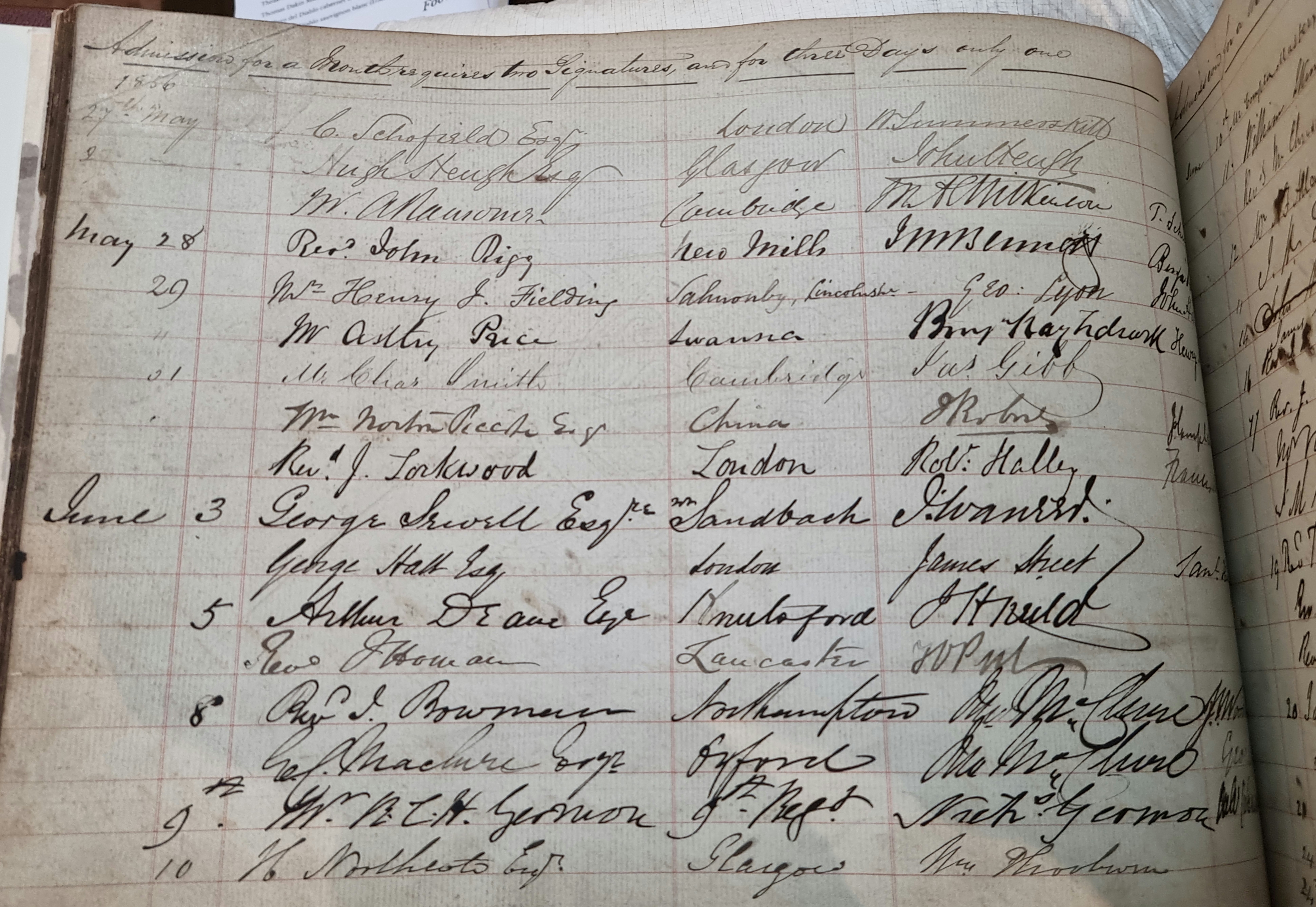

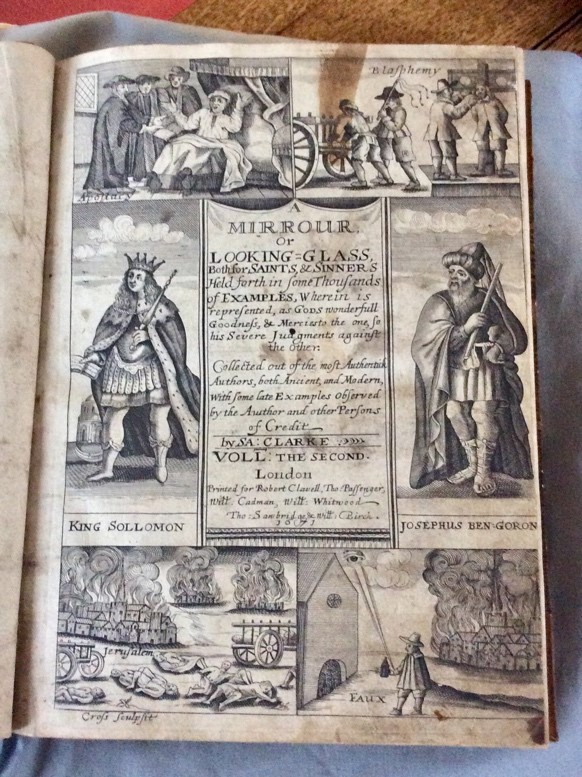

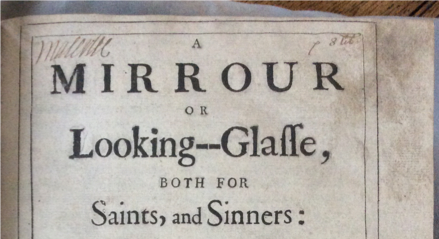

As we approach International Women’s Day with its global objectives of promoting change for women and celebrating their achievements, we thought it would be interesting to share information about a book that came to be in the library as part of our Founder’s original collection. Our edition of ‘A Mirrour, or Looking-Glasse both for Saints & Sinners,’ was published in 1671 and written by Samuel Clarke, a significant puritan pastor of the era.1 At the time of publication Clarke had been ejected from the church for his non-conformity to the requirements on religion of the Restoration monarch, Charles II. Nevertheless, he had continued to write and his 1671 text examined an enormous list of unrelated subjects, including ‘examples of women, good and bad.’ A feature of the book is that there is no rhyme or reason to the chronology or geography of the subjects covered.

In the seventeenth century these types of book, now known as looking glass histories, became popular reading and Clarke’s book has, indeed, been discussed by academics as a good example of the genre.2 In England, where Clarke’s book was published, the developing and important science of optics became associated with literature that used old and philosophical metaphors of mirrors. Between 1640 and 1660 about 185 titles containing the words mirror or looking glass were published; so it was not a flash-in-the-pan phenomenon.

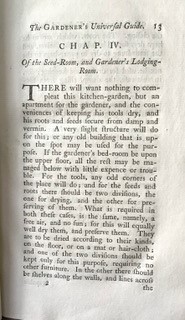

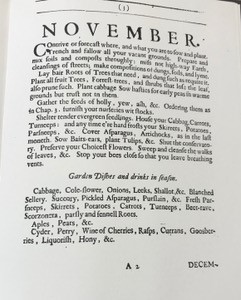

The aim of these books was not just to educate the reader in a bewilderingly large variety of topics but also to invite them to examine their own lives, as if through a mirror, in the context of examples from history and other cultures. In that way the conditions of their daily life could, in theory, be better understood; people could become agents for change in society and perhaps the future could be determined. This latter aspect might seem strange considering the religious nature of the times; but given that generally held and popular beliefs about reflective surfaces were then quite different, perhaps we should not be surprised. Although the science of optics was developing steadily, people still held onto notions that they might not see just their own reflection when they looked in a mirror. The illustrations included in the books were of a religious nature, countering superstition and reminding the reader of God’s role in daily life. Text included with these illustrations, as seen above in the picture of Clarke’s frontispiece, also reminded the reader of God’s goodness and mercy.

Clark wrote an ‘Epistle to the Reader’ or introduction, in which he outlined that previous editions had taken examples and information largely from writers who were either heathen or prophane (sic). The 1671 edition had, however, taken its sources from Christian and ecclesiastical writers. This might help to explain why the earlier editions had included several chapters on women where they were described in positive terms such as ‘women valiant’, ‘women religious’ and ‘women learned’ whereas the Innerpeffray edition of 1671 only refers to ‘women, good and bad.’ A subtle shift in perception perhaps, but still a shift.

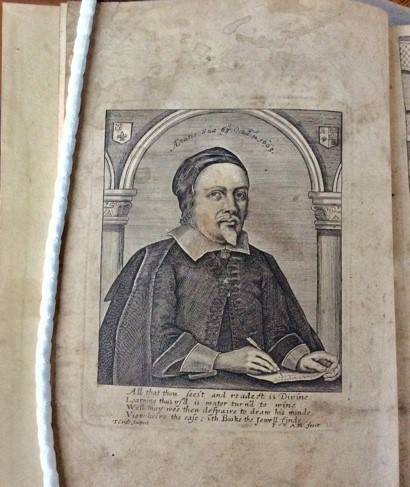

Left: an engraving of Samuel Clarke taken from the Library of Innerpeffray’s copy of “Saints & Sinners.’ The engraving is attributed to Thomas Cross3.

Clarke’s introduction to the reader also outlined that the examples outlined in his Mirrour text were of two sorts. Firstly, they would show ‘God’s severe and signal judgment on wrongdoing and wrongdoers.’ Secondly, the examples would promote an ‘….amiableness of piety and virtue.’ In other words, a wise reader should learn from the errors of others and follow good examples of behaviour in order to live a good and godly life. Particular emphasis was placed upon great men and ministers of the church to exert a good influence on others for they were ‘…looking glasses by which all about them dress themselves.’

So, having set out his premise for the text to follow, what did Clarke have to say about women? Well, many things, which viewed through the prism of present day sensibilities would be cast aside as pure sexism. But through the eyes of a seventeenth century woman, reading examples of the courage and heroism of women from the recent and distant past, it might well be viewed as inspirational and/or cautionary.

Broadly speaking, the examples of ‘women, good and bad’ can be summarized by this reader under several categories, as shown below. Other readers may interpret things differently of course but that is the nature of the looking glass! It is worth noting here that Clarke himself made no distinction in the text between what he considered to be good and bad examples of behavior in women; he simply made a list.

- Women who were praised for their beauty, appearance, actions or attributes, mostly via the endorsement or approval of a man/men – fathers, husbands, sons, armies, clergy.

- Women who were judged by other women and who might suffer reputational damage in terms of their character and morals. Queen Elizabeth I was praised by a European princess for her refusal to associate with any woman she considered to be ‘stained.’

- Women who defied their husbands (but for good causes/reasons, often to look after men working or fighting for their spouses.)

- Women who were learned and knowledgeable. Interestingly, Sappho was cited as notable for her skill in lyric poetry and the invention of Sapphic verse. No comment was made on any other aspect of her life.

- Women who went beyond what was expected of them (i.e despite their female state) in battle, leadership, public speaking, war. The examples given were mostly of women who lived in ancient times although Elizabeth I was cited once again for her famous speech to her troops at Tilbury, where she spoke of having the body of a weak and feeble woman but the stomach of a king.

- Women who prayed for death eg Queen Margaret, wife of the King of Scots, who was said to have died three days after praying for her own demise, after hearing that her husband and son had been killed in battle.

- Women who were stubborn and stood up to men despite the threat of death – in 1529 a French woman was reported by her maid to the Jesuits for having a bible in her home and for not attending mass. When she refused the Jesuits’ demand that she recant and burn her bible(!) she was burned at the stake.

- Women of conscience; for example, in 1620 an Italian woman was killed then hacked to pieces for refusing to change her religion.

- Women who acted inhumanely and without conscience. Welsh women came in for bad press here when they were castigated for their actions on the battlefield after Owen Glendower defeated Edmund Mortimer in the time of King Henry IV of England. They were said to have stripped and mutilated the bodies of dead English soldiers, then used the body parts in various disrespectful practices.

- Women who were of ‘ a lower creation’ (i.e not of the Christian faith) or who did not attend church.

Though three hundred and fifty years have passed since Samuel Clarke invited his readers to consider written examples of goodness and badness in women, present day readers may be tempted to think that some things have not changed very much. Women’s lives and situations are indeed very different now but we are still subject to inequality and superficial judgments on appearance, temperament and ability. It is still, in some respects, a man’s world and the need for International Women’s Day is still vital, to help women to achieve equality in all its forms. Samuel Clarke’s notion of the use of a looking glass might be outdated but he probably would not be surprised to learn that women (and men) are still prone to the use of mirrors. How we see ourselves in them has changed but we can still learn from their past.

Footnotes and Sources.

- Samuel Clarke (1599-1683) was a significant puritan clergyman, biographer and writer of histories. He played a part in the religious and political life of London both in the time of Charles I and Charles II, though he was later ejected from the church for his non-conformity. At the time of publication of the 1671 edition of ‘Saints & Sinners’ he was described as the sometime pastor of St.Benet Fink in London, which was a church in the Threadneedle Street area of the city. It was rebuilt by St. Christopher Wren after the 1666 Great Fire of London. St. Benet refers to St. Benedict, the founder of western monasticism whilst Fink is thought to be derived from the name of Robert Fink (or Finch) who was a thirteenth century church benefactor. Finch or Fink Lane was a street associated with Robert’s family and was located near Threadneedle Street.

Sources:

Dictionary of National Biography https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Clarke_(minister)

- Source: Looking Glass Histories, by Margaret J M Ewell, Journal of British Studies, July 2004, via

- www.researchgate.net

- Thomas Cross (the elder) was an English engraver who was known to be active between 1644 and 1682. He engraved many portraits of authors for frontispieces and title pages of books. He is also known for his work in engraving shorthand manuals (he invented his own shorthand system).

Sources: Dictionary of National Biography https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Cross_(engraver)

National Portrait Gallery, London via www.npg.org.uk

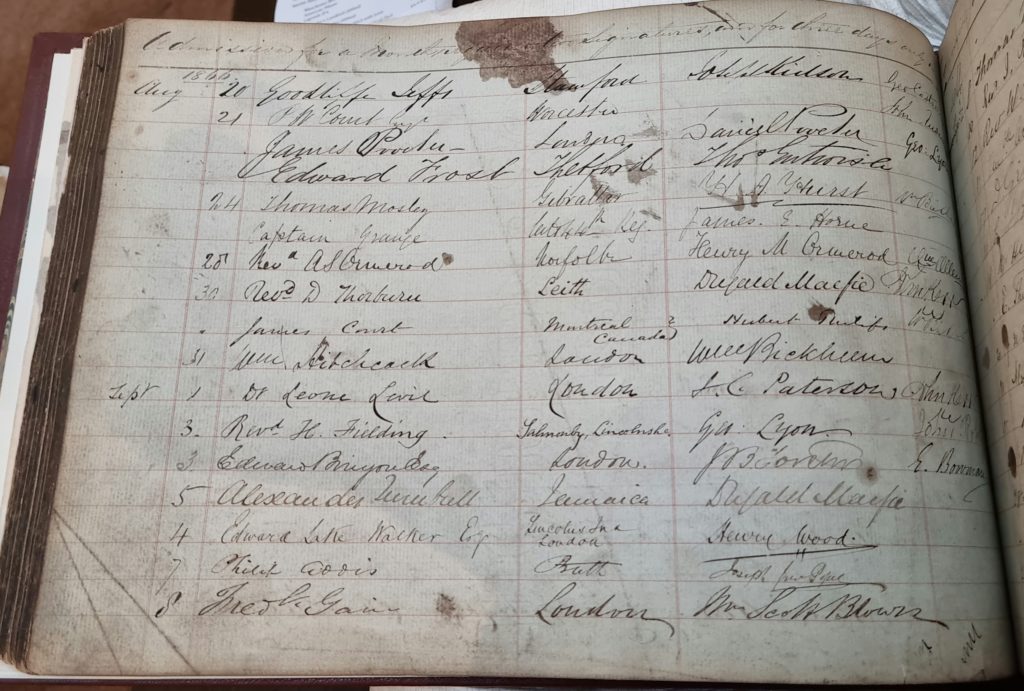

4. The signature in the photograph is that of the third Lord Madertie, David Drummond who founded the Library

of Innerpeffray in 1680, bequeathing his collection of about 450 books to the library in his will.

Shirley Williams

February 2024