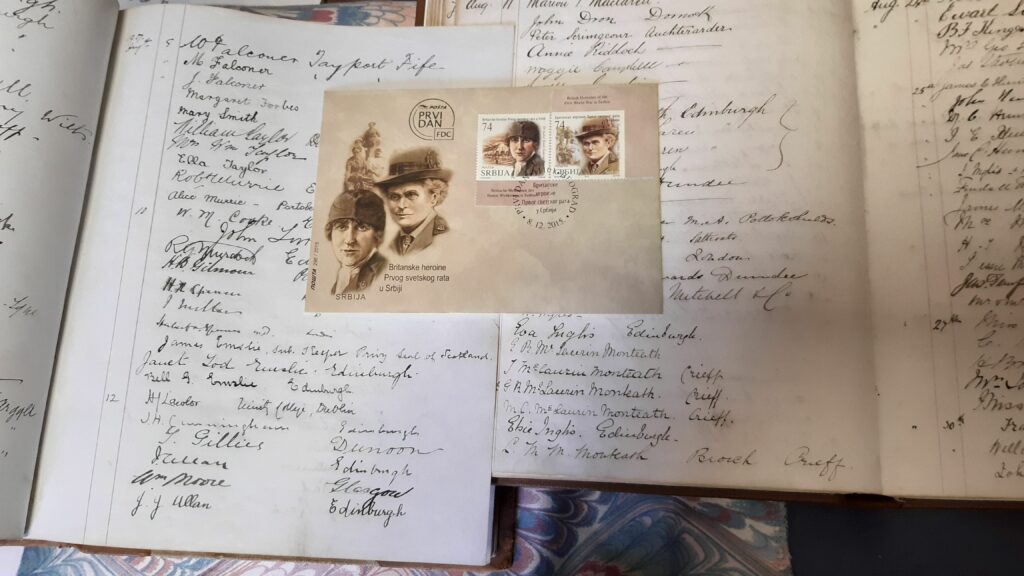

Back in 2022, Innerpeffray’s annual exhibition focused on Innovation and Invention, and we featured the signatures of two incredible women who had visited the library and signed its visitors’ books. Elsie Inglis (1864-1917) and Isabel Emslie Hutton (1887-1960) were both key members of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, working throughout Europe during World War I.

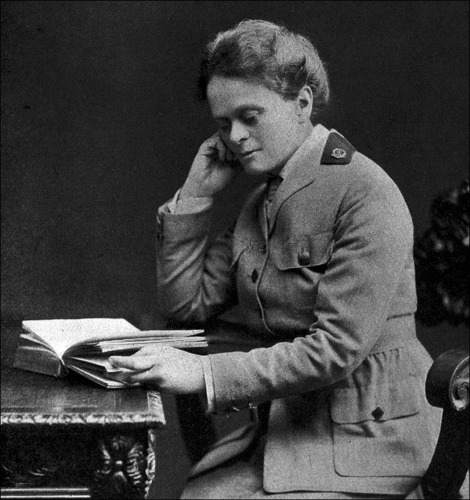

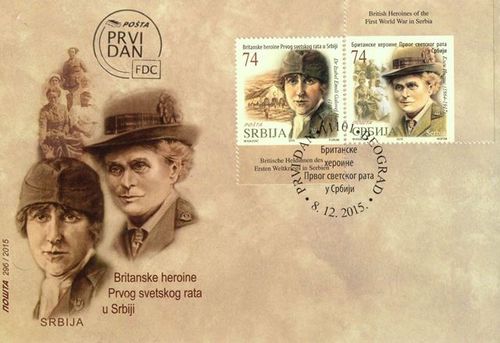

Dr Elsie Inglis, suffragist, doctor, and architect of the first world war Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service, visited Innerpeffray with her family in the summer of 1887. And twenty years later, in August 1907, the visitors’ books record the signature of Lady Isabel ‘Bell’ Galloway Emslie Hutton, who served in the Scottish Women’s Hospitals from 1915-20. Both women were honoured with international medals for their service, including the Serbian Order of the White Eagle, the highest honour available in Serbia, of which Inglis was the first female recipient.

Elsie Inglis

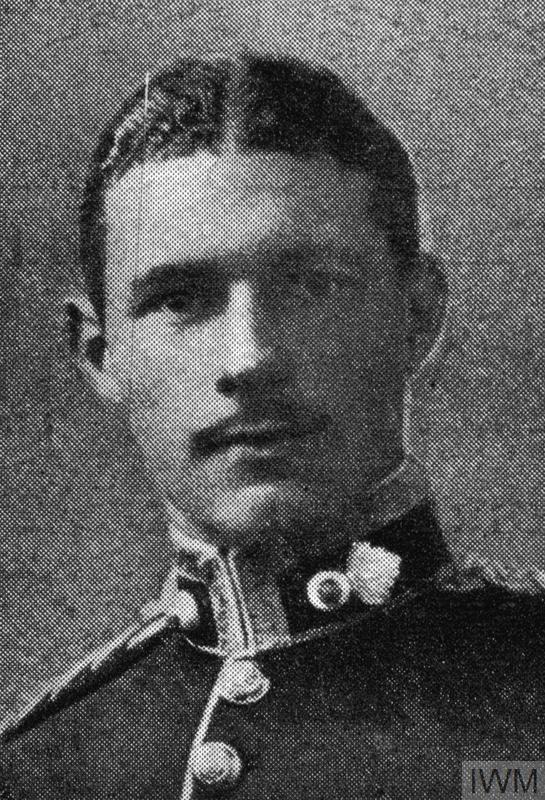

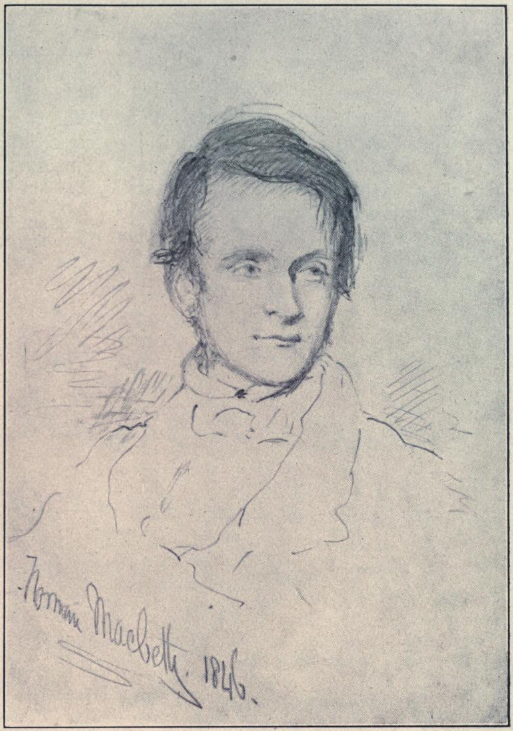

Eliza Maud “Elsie” Inglis was born on 16th August 1864 in the Himalayan city of Naini Tal to mother, Harriet Thompson, and father, John Forbes David Inglis, magistrate in the East India Company. Around 1876-1879, the Inglis family returned to Scotland from India, via South Africa and Australia, and settled in Bruntsfield, Edinburgh. In October 1886, Inglis enrolled in the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women, newly established by Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1913; Scotland’s first female doctor).[1]

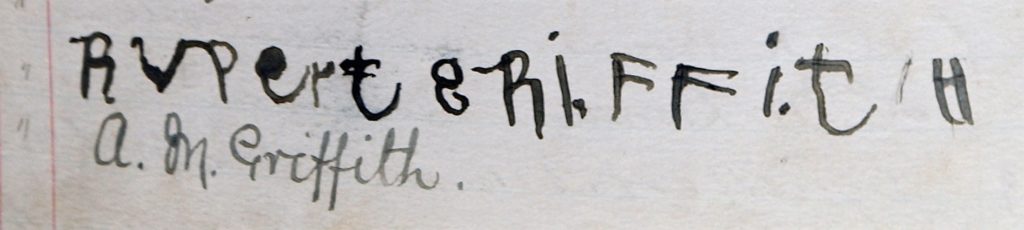

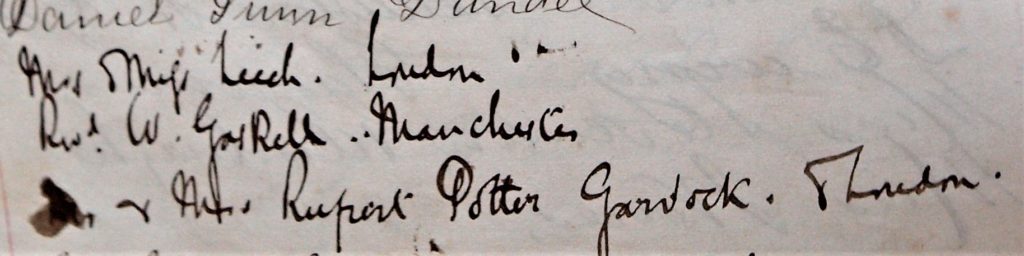

The following year, Inglis visited the Library of Innerpeffray! There are some signatures within the visitors’ books that make me gasp with delight when I read them for the first time. Elsie Inglis’ signature was one of those.

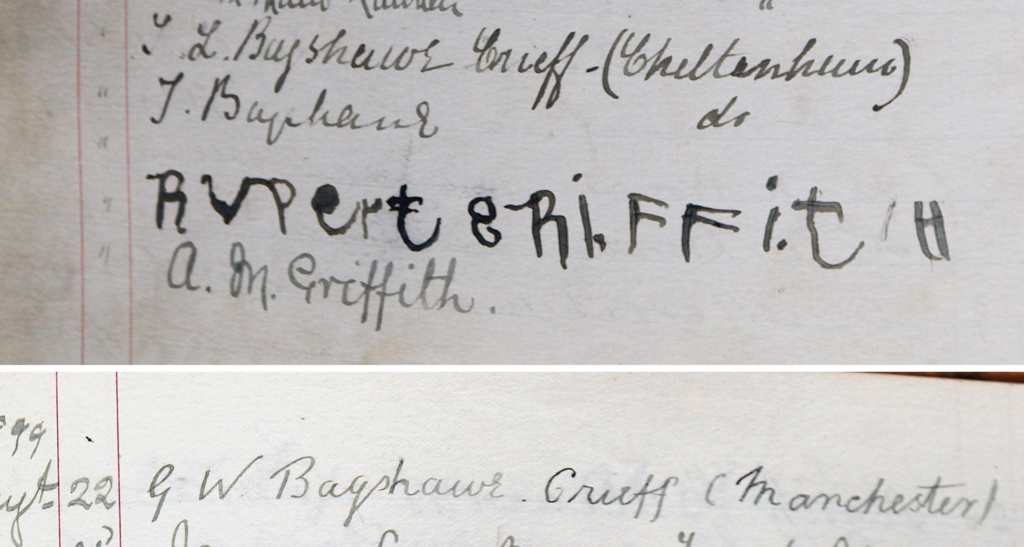

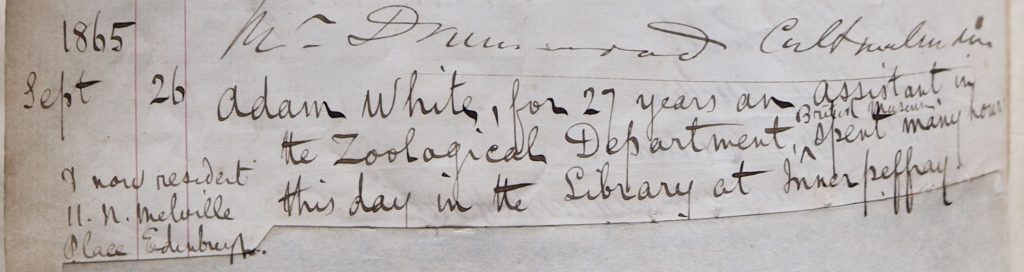

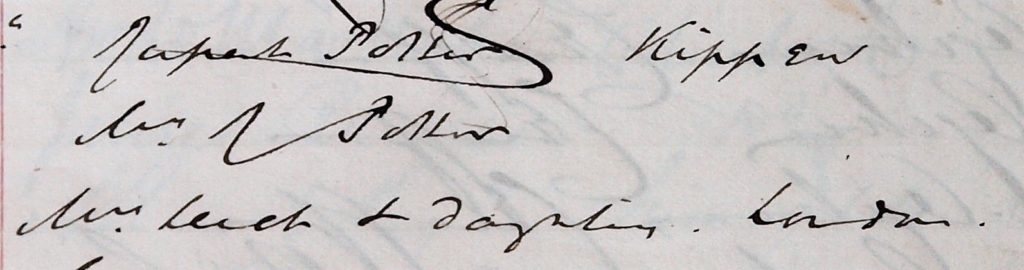

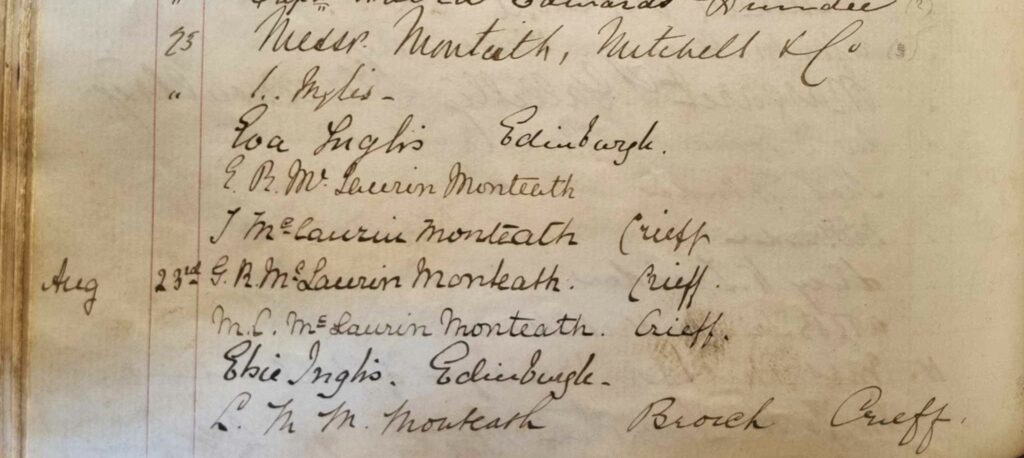

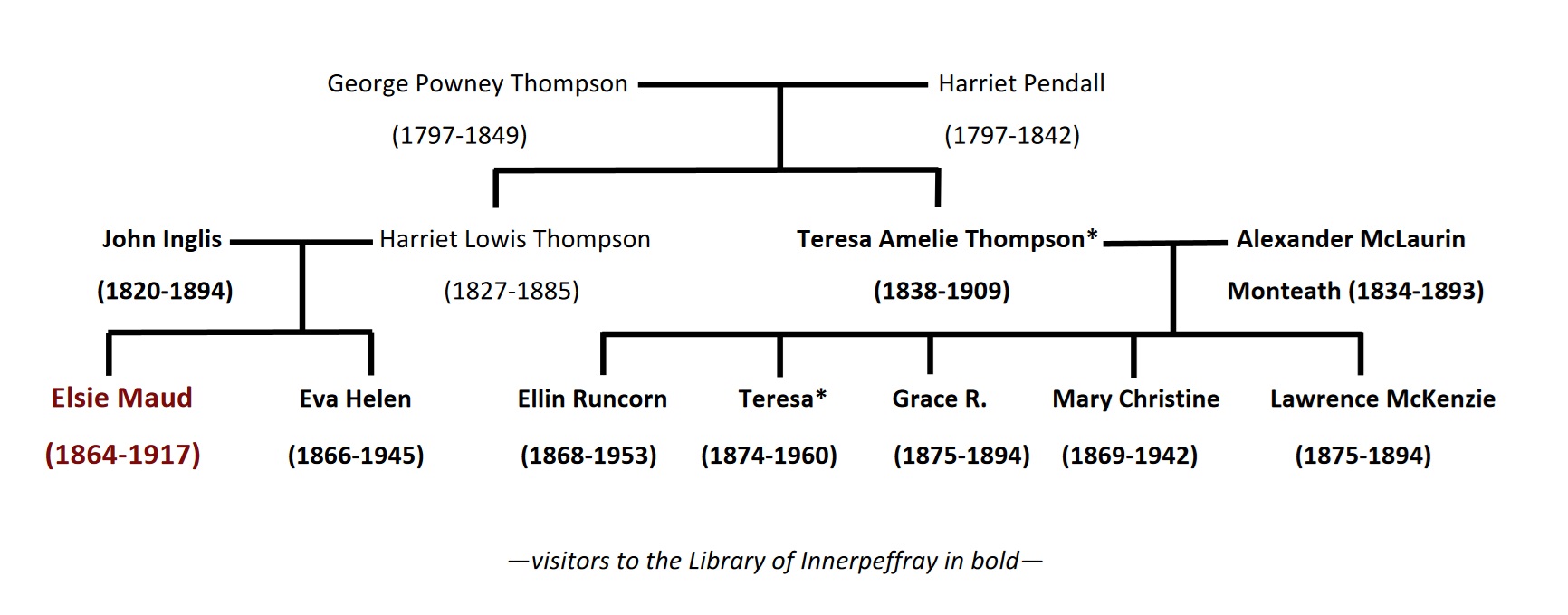

On Tuesday 23rd August 1887, just after her 23rd birthday, Inglis visited Innerpeffray accompanied by family members from both Edinburgh and Crieff: her father John and sister Eva Helen, and her cousins Ellin Runcorn, Teresa, Grace Rivers, Mary Christine and Lawrence McKenzie McLaurin Monteath. The first signature of the travelling party reads, “Messr. Monteath, Mitchell & Co”, which may indicate that the following men were also present: Alexander McLaurin Monteath, Elsie’s uncle; and perhaps Dr. Richard Ashmore Mitchell (1856-1926), who married Ellin Runcorn the following year, in 1888; and/or Ellin’s future father-in-law, Henry Mitchell (1823-1901). According to Alexander Porteous’ History of Crieff (1912), Alexander McLaurin Monteath was the Director-General of the Post Office in India.[2] While visiting Crieff, the Inglis family would likely have been staying with the McLaurin Monteath family at Broich Cottage.

Just a couple of days later, on Thursday 25th August, the signature “J. Inglis & party” from Edinburgh is entered in the visitors’ book, along with the number 8 in brackets. I think we can infer from this that the entire Inglis-McLaurin Monteath clan were so charmed with Innerpeffray that they came back for a second visit!

In 1889, Inglis left Jex-Blake’s school, partially due to the expulsion of two fellow students, Grace and Martha Georgina Cadell, who went on to successfully sue Jex-Blake and the school. Then in 1890, Inglis and her father established the Medical College for Women on Chambers Street in Edinburgh, in direct competition with Jex-Blake. The Cadell sisters and Inglis all finished their medical education at the new Medical College for Women, and later that year, Inglis joined the National Society for Women’s Suffrage. In 1906, Inglis co-founded the Scottish Women’s Suffragette Federation, where she acted as Honorary Secretary until 1914.

After passing her exams in 1892 and becoming Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, Edinburgh and Glasgow, Inglis worked in Edinburgh, London and Dublin, specialising in midwifery and maternity and focusing on improving conditions for impoverished women.

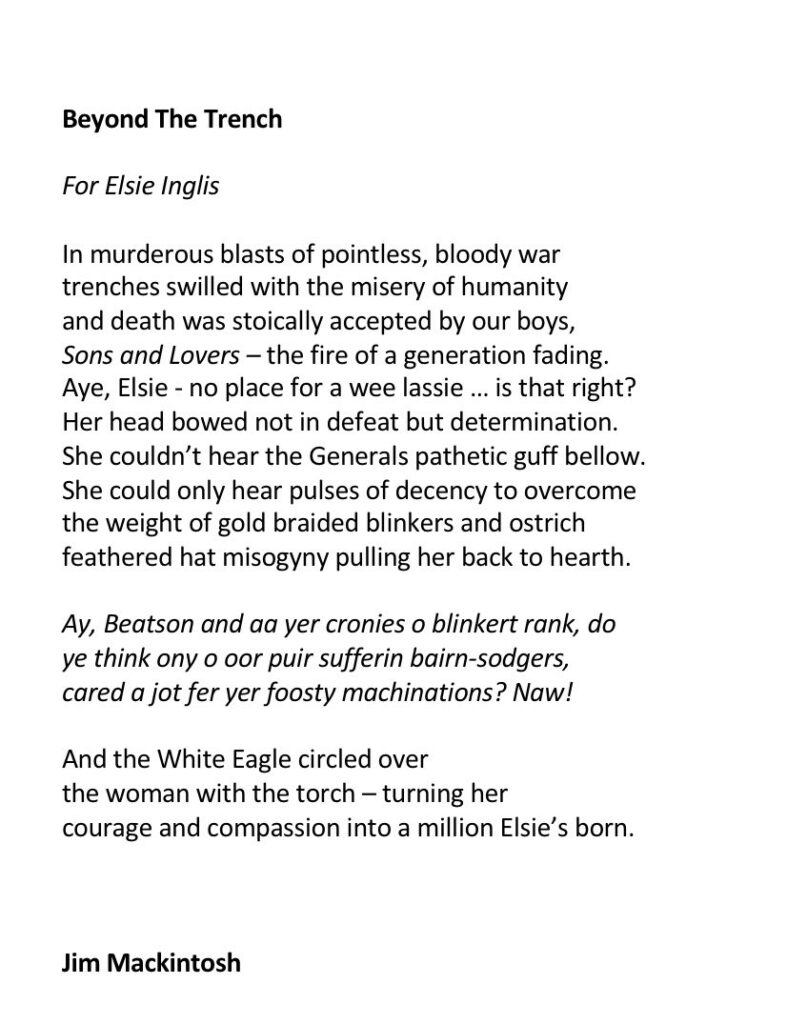

In 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War One, Inglis, aged 50, a respected consultant, physician and surgeon, offered her services to the Royal Army Medical Corp. She was told,

“My good lady, go home and sit still.”

Isabel Galloway Emslie Hutton

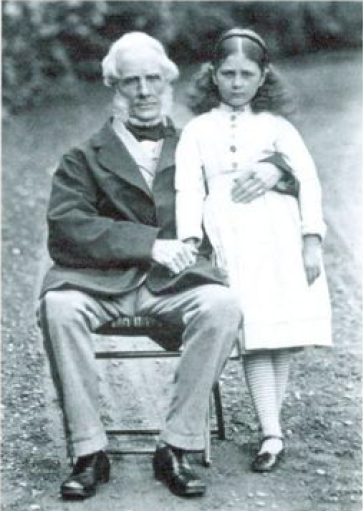

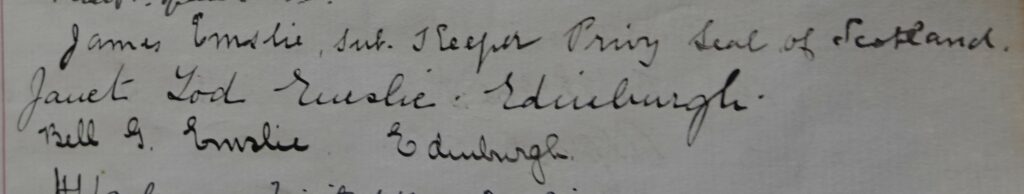

Nineteen days after Elsie Inglis’ first visit to Innerpeffray Library, on 11th September 1887, Isabel Galloway Emslie (later Hutton) was born in Edinburgh to Janet Tod Emslie and James Emslie, Advocate and Substitute Keeper of the Privy Seal of Scotland.

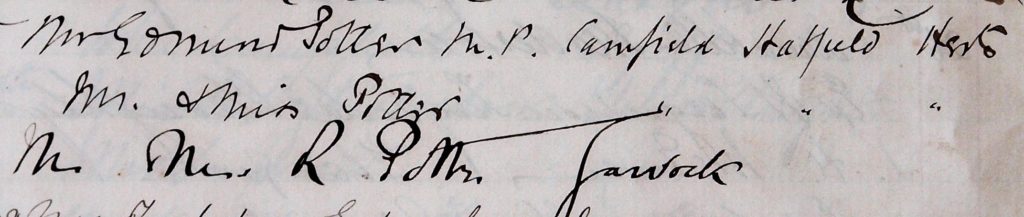

Aged 19, on 10th August 1907, Emslie visited the Library of Innerpeffray with her parents, signing the visitors’ book as “Bell”. Only after looking into her father, James Emslie, did I discover the link to his eminent daughter and the career she was just beginning. From 1910 to 1912, Emslie graduated from the University of Edinburgh and gained her M.D., specialising in pathology and psychiatry. Between 1912 and 1915, she worked at the Stirling District Asylum, the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh and the Royal Edinburgh Hospital.

It was 1915 when Emslie went to the War Office in Edinburgh, where she was rejected by the Royal Army Medical Corp. A young policeman stopped her as she watched young recruits and said,

“Ye’d be better at hame knittin’ socks for the lads.”[4]

Scottish Women’s Hospitals

Not in any way deterred by these statements, both Inglis and Emslie went on to do extraordinary work during the First World War.

After having her services refused by the British Government, Inglis offered help to the French Government, who accepted. Inglis founded the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Home and Foreign Service (soon shortened to SWH) – women-staffed field hospitals welcomed by the Allies and established initially in France, Greece and Serbia.

In October 1914, Inglis wrote a letter to a fellow suffrage campaigner, Millicent Fawcett, in which she said,

“I cannot think of anything more calculated to bring home to men the fact that women can help intelligently in any kind of work. So much of our work is done where they cannot see it. They’ll see every bit of this.”[5]

Throughout 1915, Inglis acted as Chief Medical Officer in charge of the First Serbian Unit of the SWH in Kragujevac. In October, Serbia was invaded on two fronts and SWH staff were ordered to accompany the soldiers retreating over the Albanian border. Inglis refused to leave her seriously ill patients and, accompanied by fellow medical staff, was taken as a Prisoner of War by Germany. As Prisoners of War the women were allowed to keep working until their patients were well, at which point they were repatriated, via Belgrade, Vienna and Zurich, reaching Britain in February 1916. Inglis immediately took off for Odesa, establishing a SWH team in what was then Russia. In April of that year, the Crown Prince of Serbia awarded Inglis with the Order of the White Eagle – the highest medal in Serbia’s power to bestow. Inglis was the first ever female recipient.

On 26th November 1917, just days before returning home to Edinburgh from the Russian front, Inglis died in Newcastle. Despite never meeting in person, Emslie wrote in her diary,

“Dr. Elsie Inglis had gone, however, to her rest; tired out, but valiant in the end, she had slipped away the day after arriving from Russia, whence she had brought the Jugo-Slavs so that they might go to the help of their brothers in Serbia. But she lived in others, and her inspiration kept us all going and ever striving to higher things.”[6]

Inglis was honoured with a full military funeral in St. Giles Cathedral and was buried in Dean Cemetery, Edinburgh. In July 1925, ‘The Elsie Inglis Memorial Maternity Hospital’ was built in Edinburgh using surplus funds from the SWH. Children born there were known as “Elsie’s Babies”.

Inglis’ medals are now stored at the Surgeon’s Hall Museums in Edinburgh. From left to right, these medals are described as follows: “Given by the Russian Government under the late Czar”, “The Great International War Medal”, “Order of the White Eagle”, “Medal struck to commemorate the work of the Scottish Women’s Hospitals”, “From the British Committee of the French Red Cross.”

Emslie had signed up to the SWH in August 1915 and was working as an Assistant Medical Officer and Pathologist in Champagne, France. In November 1915, her unit reached Salonika, Greece, accompanied by Flora Sandes, who would go on to become a sergeant in the Serbian Army. In 1918, after three years on the staff of the SWH, Emslie was promoted to command the hospital at Ostrovo, Serbia. Before leaving Serbia, Emslie was awarded with the Order of the White Eagle, the Order of Saint Sava, the French War Cross and the Russian Order of St. Anna.

After the war, Emslie worked with Lady Muriel Paget’s Child Welfare Scheme and housed almost 140,000 Crimean refugees and orphaned children. Throughout the rest of her life, Emslie worked in hospitals for the poor and served as the Director of the Indian Red Cross during the Second World War. She died at home in London in January 1960 and was buried with her parents in Grange Cemetery, Edinburgh.

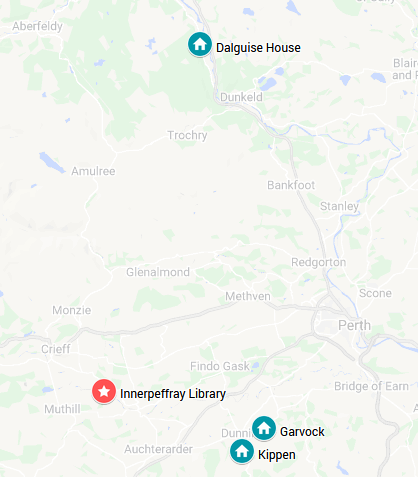

It’s an interesting coincidence that while she was working in Crimea, Emslie crossed paths with the Honourable Claude Hay (1862-1920), who was related to the founding family of Innerpeffray. Claude Hay was the fifth son of George Hay-Drummond, the 12th Earl of Kinnoull (1827-1897), who was in turn the great-grandson of Robert Hay-Drummond (1711-1776), who inherited Innerpeffray from our founder, David Drummond, 3rd Lord Madertie (1611-1694).

Emslie described Hay in her 1928 book, With a Woman’s Unit in Serbia, Salonika and Sebastopol:

“Mr. Hay was always faultlessly turned out, and was dressed exactly as if he were walking down Picadilly to have lunch at his club; he often drove in an old Victoria, which, if it had not been for the bequilted and touzled isvostchik (driver), was exactly suited to his style. He worked hard and in a most business-like way, and was much respected and loved by the Russians, to whom his courtly manners and quaint ways made a great appeal.”[7]

Hay was in Crimea representing The Daily Telegraph and apparently often told war stories of his great-uncle, Captain Hon. Robert Hay-Drummond (1831-1855), who fought in the Crimean War as part of the Coldstream Guards. Indeed, apparently Robert Hay-Drummond appointed James Christie as Librarian and Schoolmaster of Innerpeffray by letter written from the front lines in 1855.[8] It makes me wonder if Emslie and Hay ever spoke about Innerpeffray.

By Armistice Day, 11th November 1918, 14 Scottish Women’s Hospitals, staffed by more than 1000 women, had worked in six different countries and saved countless lives. Elsie Inglis and Isabel Emslie Hutton refused to sit still or go home and knit socks, and instead made lasting contributions to medicine and the wider world.

After viewing the 2022 exhibition at Innerpeffray, Perthshire poet Jim Mackintosh was inspired to pen the following poem, which he has kindly allowed me to share here.

[1] William Arthur Chase, Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1912) (after Samuel Lawrence), Royal Free Hospital, London, B117 <https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/sophia-jex-blake-18401912-123862>.

[2] Alexander Porteous, The History of Crieff From the Earliest Times to the Dawn of the Twentieth Century (Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1912), p. 79.

[3] Between the Lines: Letters and Diaries from Elsie Inglis’s Russian Unit, ed. by Audrey Fawcett Cahill (Pentland Press, 1999).

[4] Isabel Emslie Hutton, With a Women’s Unit in Serbia, Salonika and Sebastopol (Williams and Norgate, 1928), p. 16.

[5] Elsie Inglis, ‘Letter to Millicent Fawcett’, 9 October 1914, cited in Audrey Fawcett Cahill, Between the Lines: Letters and Diaries from Elsie Inglis’ Russian Unit.

[6] Emslie Hutton, p. 132.

[7] Emslie Hutton, p. 262.

[8] George Chamier, The First Light: The Story of Innerpeffray (Library of Innerpeffray, 2009), p. 66.