2023 marks the tercentenary of the birth of Adam Smith, the celebrated Scottish philosopher, political economist, author and leading participant in the Scottish Enlightenment. Events are taking place in many places, but particularly in Scotland, to mark the life of the man whose pioneering work and thinking on political economy influenced individuals, organisations and governments to think again about how a nation’s wealth is built and developed. Today, many would call Smith the father of capitalism and free market thinking.

Reproduced under a Creative Commons Licence granted by the National Portrait Gallery, London.

To mark the tercentenary the following post will share information about two editions of Smith’s most famous work, An Inquiry Into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations, which are on the shelves of the Library of Innerpeffray.

Smith spent many years studying economics, trade and business before writing The Wealth of Nations and the final text covered subjects such as the division of labour, growth and productivity, competition, laissez-faire systems, free trade and free markets. He also included his thoughts on empire, colonialism and slavery and proposed schemes for both a gradual devolution of the British Empire and a theoretical scheme for imperial federation. These schemes left an ambiguous legacy that affected political and economic debate on empire for a very long time.

The Wealth of Nations influenced many economic thinkers, perhaps most famously, Karl Marx. But where Smith’s thinking on social evolution centred on human nature and the individual’s desire for self-betterment, Marx concentrated on social change being engineered through a struggle between different socio-economic classes.

Five editions of the book were published in Adam Smith’s lifetime and he added corrections and footnotes to some of these; many other editions were published after his death in 1790.

The Innerpeffray Acquisitions

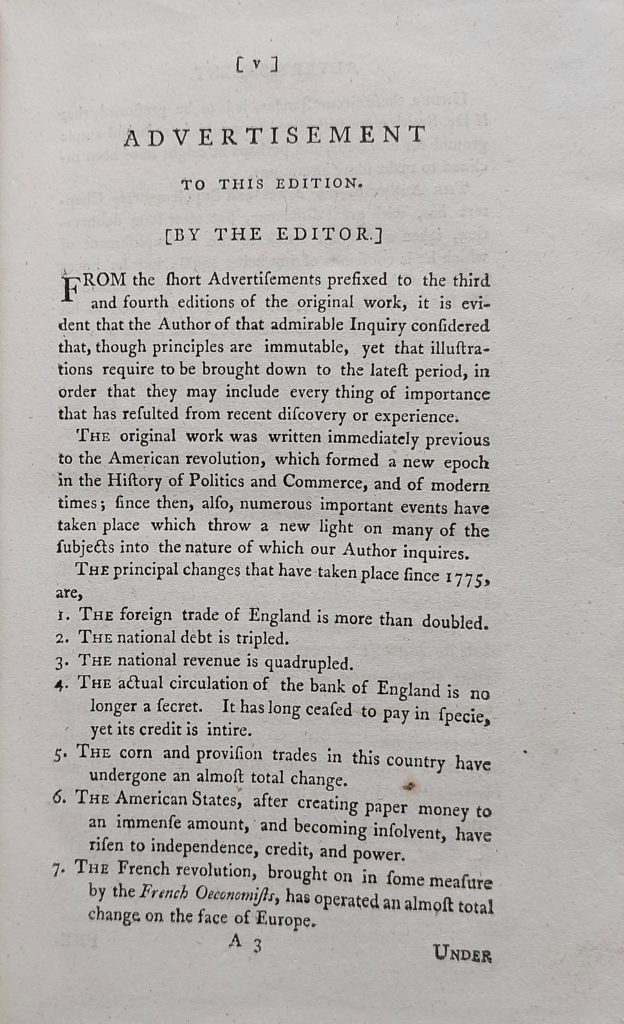

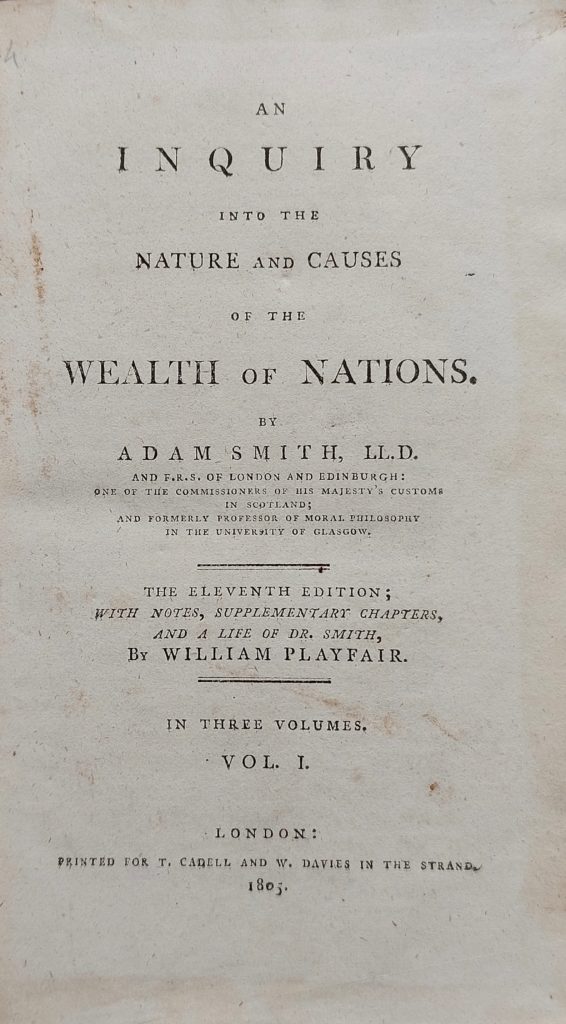

Many of the library’s 18th century books were acquired at the instigation of Robert Hay Drummond (RHD), who inherited the Innerpeffray estate and thereby responsibility for the Library of Innerpeffray. RHD died in 1776, the year of publication of The Wealth of Nations, and no copy of it had been bought for his collection. In 2008 a local man, Tony Murray of Dollerie, Laird of Crieff and a Friend of Innerpeffray Library, donated his copy of the book (in three volumes) via a long-term loan to the library, to rectify this significant absence from the collection. It is an eleventh edition published in London in 1805 by T. Cadell and W.Davies.

The eleventh edition contains a page reprinted from the fourth edition where Smith wrote ‘an ‘advertisement’ about the contribution of information from Mr. Henry Hope of the Bank of Amsterdam. Hope was an important merchant banker in Holland and, it would seem, provided information that was important enough to Smith to warrant a very specific acknowledgement.

In 2013 the library received an important gift from an American bibliophile of Scottish descent, Janet Burns St Germain. Amongst this donation was a copy of the second continental edition of The Wealth of Nations, in four volumes. This edition was published in 1801 by James Decker (of Basle) and the Levrault brothers (of Paris) and it was the only edition to include an English translation of ‘Reflections on the Formation and Distribution of Riches’ by the French economist and administrator, Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot, Baron de l’Aulne.

Turgot’s book, published in 1766, had a great influence upon Adam Smith and has been described as “…the best work on the science published previous to the Wealth of Nations.”

In his youth Turgot was influenced by scientific curiosity, liberalism, tolerance and social evolution. He became friendly with philosophers of the school of physiocratic thought, which is now generally regarded as being the first scientific school of economics.

He was a talented and reforming administrator who served both Louis XV and Louis XVI. His attempts to reform France’s finances over his years of service to the crown were blocked by the privileged classes of France and he eventually fell out of favour with Louis XVI.

The Life and Times of Adam Smith

Smith was born in 1723 to Adam Smith (Senior), a Comptroller of Customs in Kirkcaldy, and Margaret Douglas, the daughter of a wealthy landowner. Little is known of his early life other than a report that when he was four years old when he was four years old he was allegedly “abducted by gypsies” and then rescued.

His early education took place in Kirkcaldy and from there he went on, aged 14, to the University of Glasgow, an institution that was already centrally placed within the Scottish Enlightenment. At Glasgow, Smith became influenced by Francis Hutcheson, Professor of Moral Philosophy, who was an exponent of a theory that a person’s ‘moral sense’ could help them to make the right decisions and take appropriate actions in life. This influence played a part in Smith’s later work where he included aspects on human nature in his writing. For instance, in The Wealth of Nations he considers the struggle of the inner man “the impartial approval or condemnation of personal/others’ actions with a voice impossible to disregard” versus individual desire for self-interest or self-preservation.

In 1740, Smith graduated and gained a scholarship to Balliol College at the University of Oxford. He found life there less stimulating than at Glasgow and spent much of his time in self-education, largely in classical and contemporary philosophy. Six years later he gave a series of lectures in Edinburgh on rhetoric, history and economics, impressing his contemporaries in the process.

In 1751, aged 27, Smith was appointed by the University of Glasgow to the position of Professor of Logic and within two years he was appointed Professor of Moral Philosophy, a subject that covered theology, ethics, jurisprudence and political economy. Smith threw himself into his work at the University, teaching up to 90 students (aged 14-16) at a time. He taught them in English not Latin, a precedent which had been set by his own professor, Francis Hutcheson.

Smith also participated in Glasgow society, mixing with aristocrats, scientists, intellectuals and leading members of the Enlightenment, e.g., the philosopher David Hume, engineer James Watt, and Joseph Black, a pioneer in chemistry. Smith also met Robert Foulis, an important printer and publisher (who was also taught by Francis Hutcheson), and merchants and businessmen who were involved in colonial trade such as Andrew Cochrane, the founder of the Political Economy Club. These businessmen gave Smith important insights into the world of business and they influenced the ‘real world’ feel to the writing of the Wealth of Nations.

Smith’s life in Glasgow was a good one, both professionally and socially, and he described his time there as ‘…the happiest and most honourable period of my life.’ He published his first book “The Theory of Moral Sentiments’ in 1759.

In 1760, he was appointed Dean of the Faculty of Arts and in 1762 the university deferred the title LL.D upon him; but the following year he gave up his position to become a private tutor. He took up a role as tutor to the Duke of Buccleuch which was well paid and involved travelling to France where he met writer and philosopher Voltaire, economist and physician Quesney and Turgot, whose influence has already been commented upon above.

Smith returned to Britain in 1766 and for a period of years lived both in London and Kirkcaldy. During this time he was appointed a Fellow of the Royal Society of London (1773) and, of course, in 1776 published The Wealth of Nations, a book that had been at least ten years in the making. The book would bring him lasting fame and contribute not only to a new style of economic thinking but also to the rise of classical liberalism, a doctrine which held that governments should protect individual freedoms and liberties and protect people from the harmful actions of others.

Whilst he was living in Kirkcaldy, Smith spent much time caring for his mother; she died in 1784 when he was sixty-one. He did have an active social life during this time, visiting with and entertaining friends such as Irish statesmen and philosopher Edmund Burke, geologist James Hutton and two Prime Ministers- Lord North and Pitt the Younger. Stimulating company indeed! Additionally he took an active role in learned organisations such as the Oyster Club, the Poker Club and the Select Society; his friend and Enlightenment philosopher David Hume was also a member of the latter.

In his later years Smith was appointed in 1778 as Commissioner of His Majesty’s Customs in Scotland and moved back to Edinburgh. This appointment could be seen as somewhat ironic- a prominent advocate of free trade was now in charge of enforcing government rules and regulations on commerce. But Smith was never a complete economic libertarian and his father had been in the same trade, so the acceptance of the appointment is not wholly surprising. In 1783 he helped to found the Royal Society of Edinburgh and in 1787 the University of Glasgow appointed him as Lord Rector, an appointment he held until his death.

Adam Smith never married or had children though he did have a love interest during his young adult life; Dugald Stewart reports that she was ‘a young lady of great beauty and accomplishment.’ Her name is not known and neither is it known why a marriage did not result from the relationship.

He died in July 1790 and is buried at Canongate in Edinburgh.

Adam Smith led an extraordinary life: the life of an intellectual, a pioneer, and a participant in one of the greatest periods of progress and innovation the world has seen.

He left a legacy that is still recognised as important and books that are still read by students and people with an interest in economics, social history and politics. Organisations which he helped to found and/or promote still exist and prosper, statues have been erected, modern economic thinktanks are named after him and he is listed as a great Scot by many national organisations and media outlets. Three hundred years have passed since Adam Smith was born but I suspect that his intellectual legacy and importance is such that he will be remembered for many hundreds of years to come.

SW