A Talk by Jean Ann Scott Miller – blog by Sophie Wood

On 13th April 2022, the Library of Innerpeffray hosted a talk in its schoolroom about the foundation of our fundraising and support society: Friends of Innerpeffray Library (FOIL). The talk was given by one of FOIL’s founding members, Jean Ann Scott Miller, who continues to volunteer and lend her support to the library frequently.

Jean Ann started the talk with a contextual outline of the library – beginning with Friends of old.

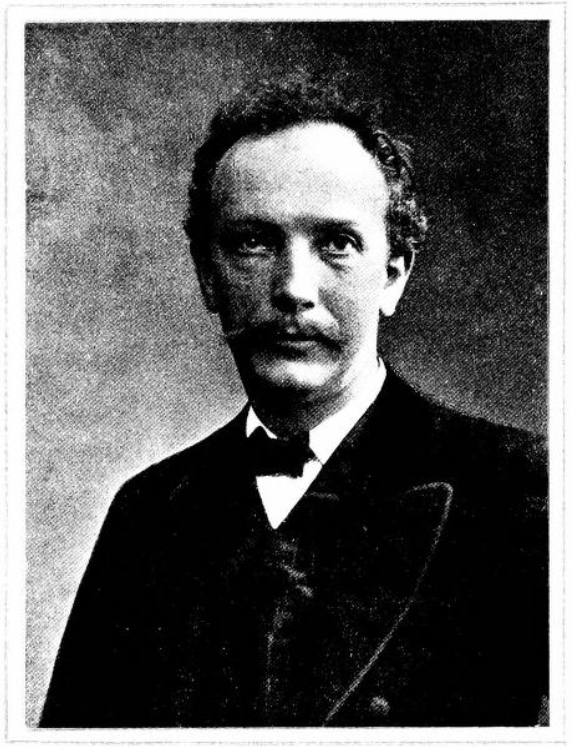

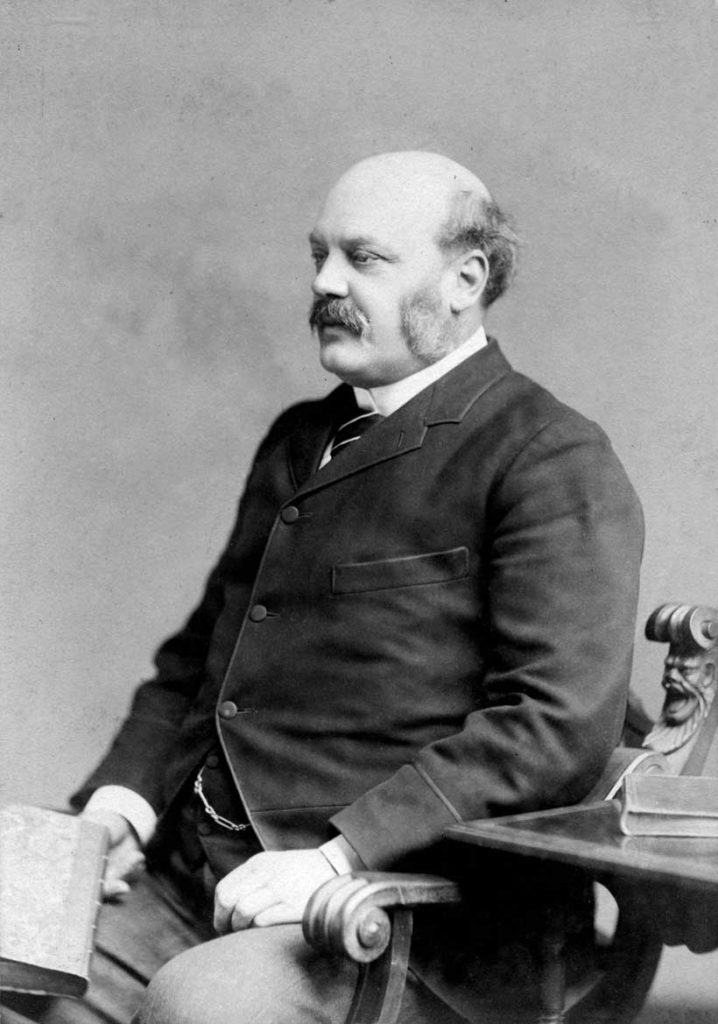

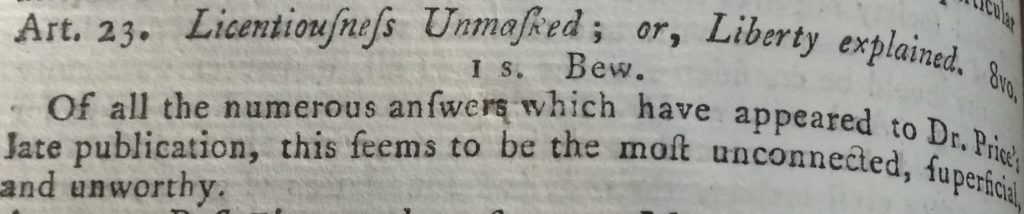

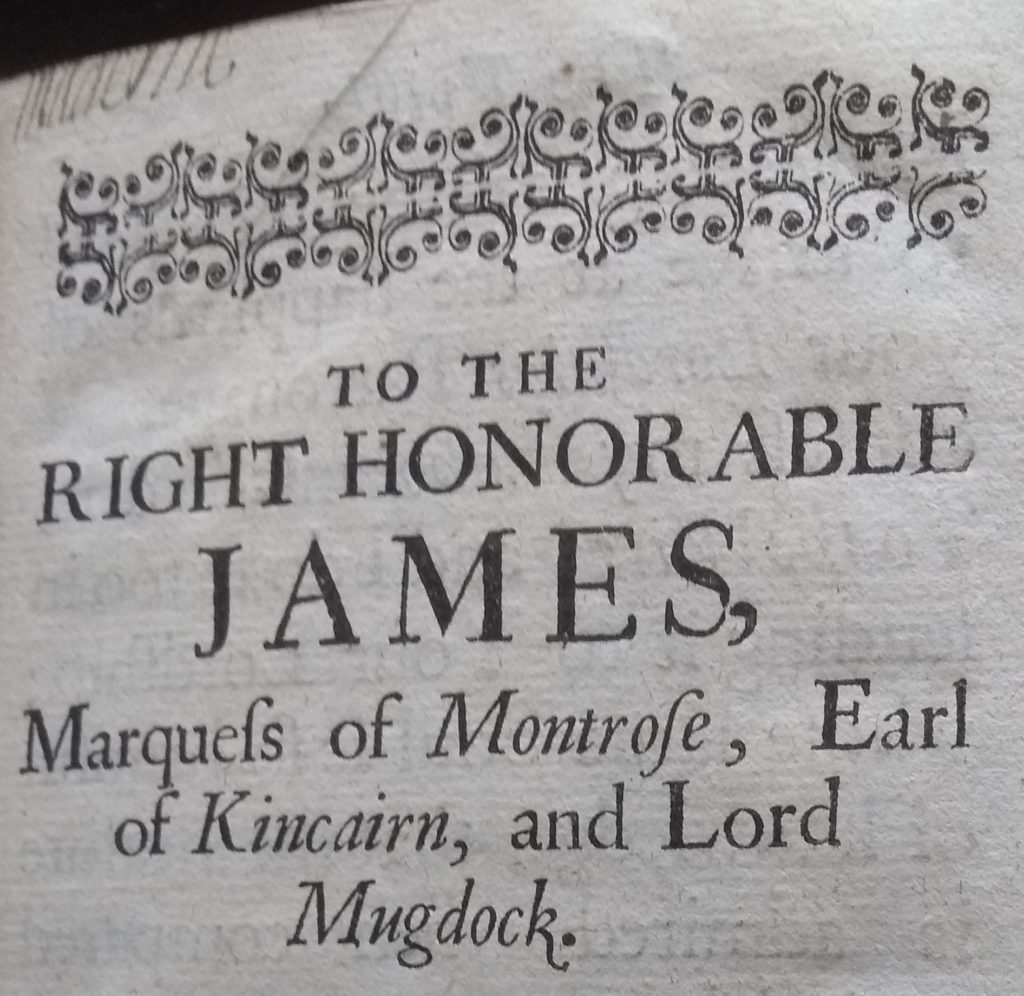

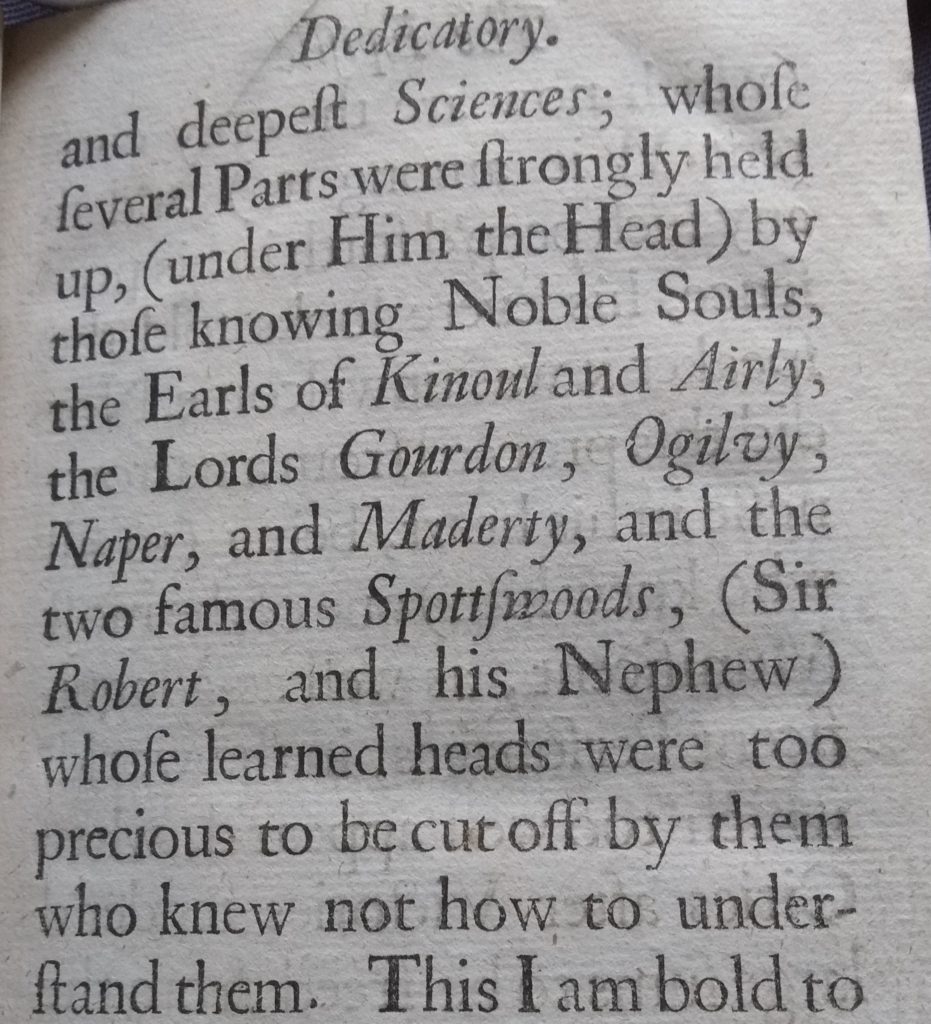

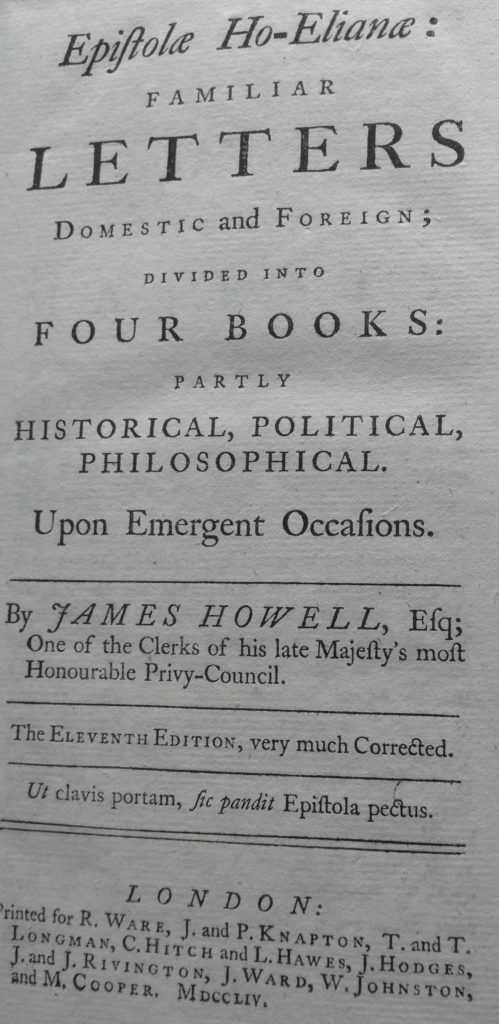

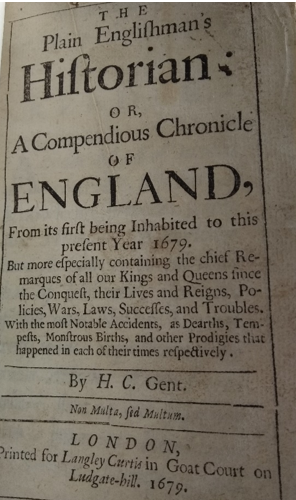

David Drummond, 3rd Lord Madertie

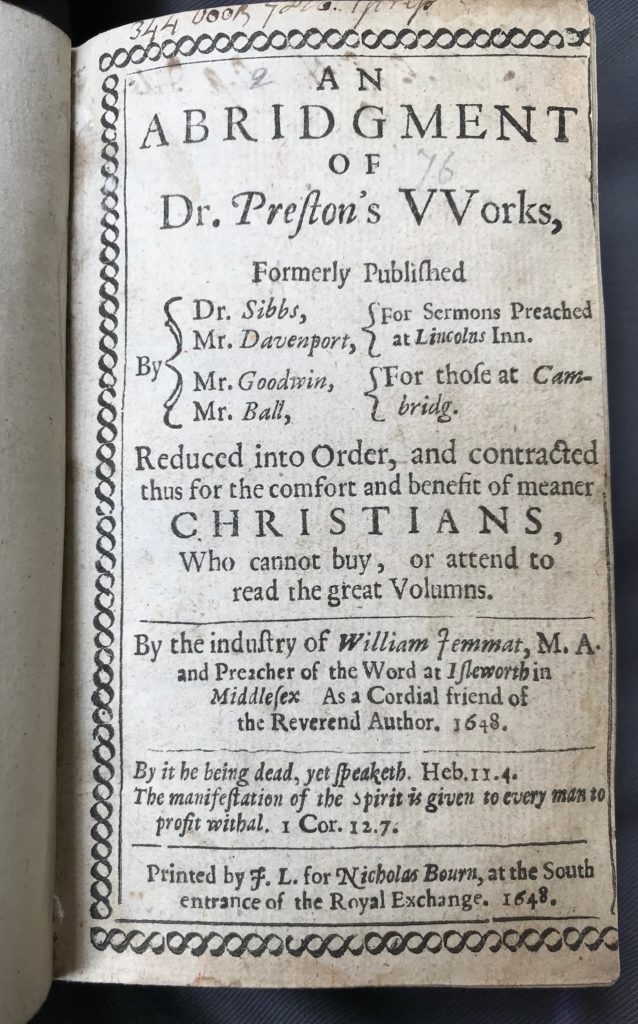

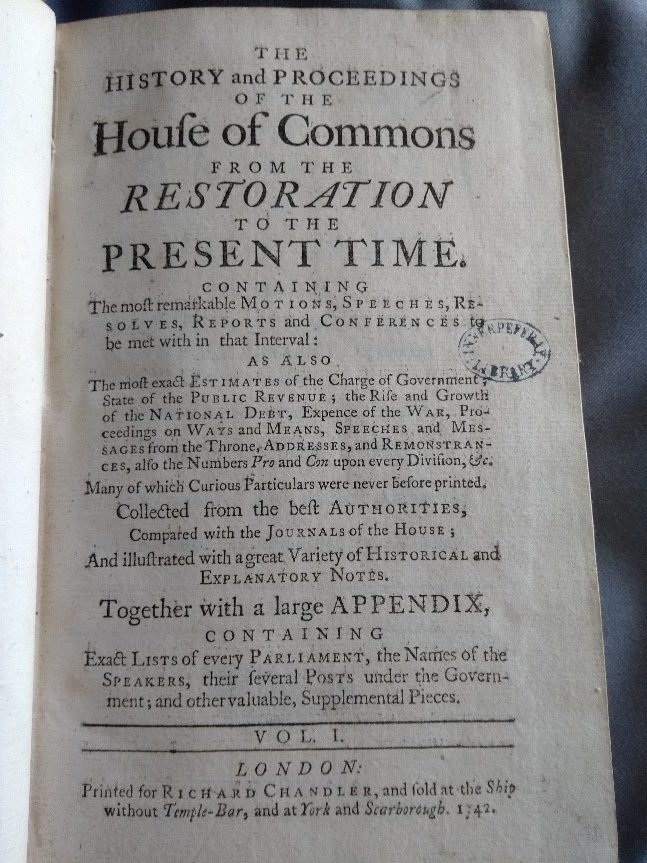

Anyone familiar with the library knows the story of our founder, David Drummond, Lord Madertie. “The first and greatest” friend of the library, his incredible generosity in opening his personal library to the public in 1680 led to a centuries long story of education and enterprise. From a small room in the chapel to what it is today, we have Lord Madertie to thank.

William Drummond 4th Lord Madertie

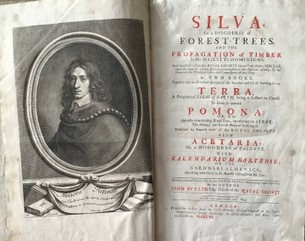

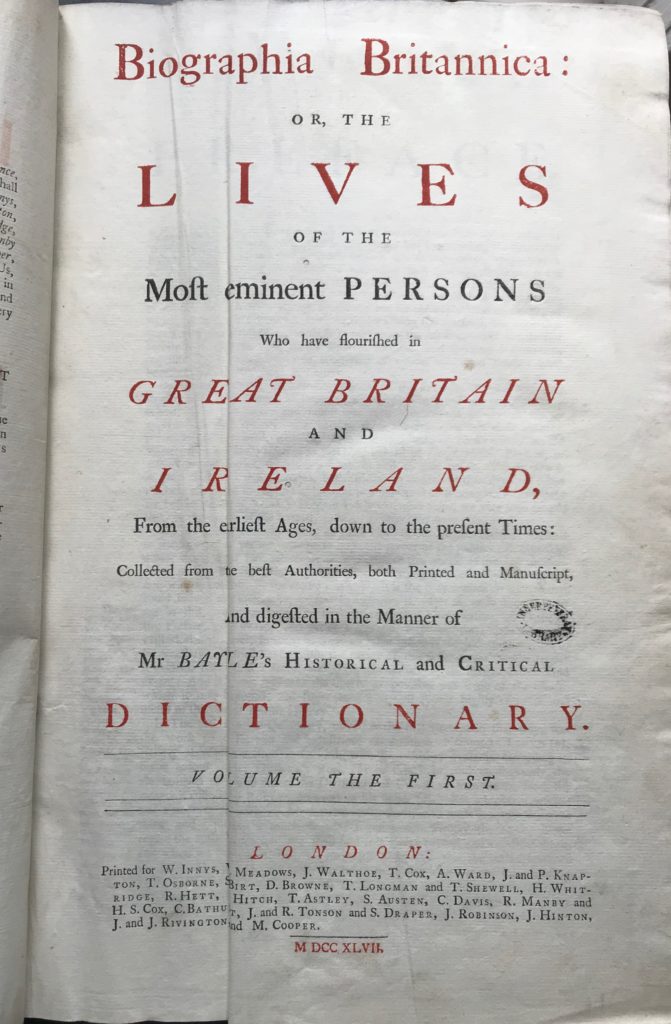

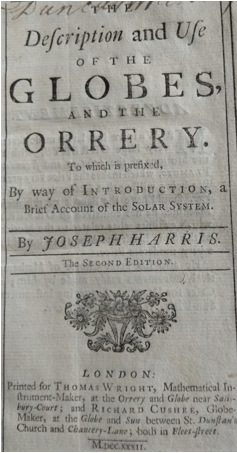

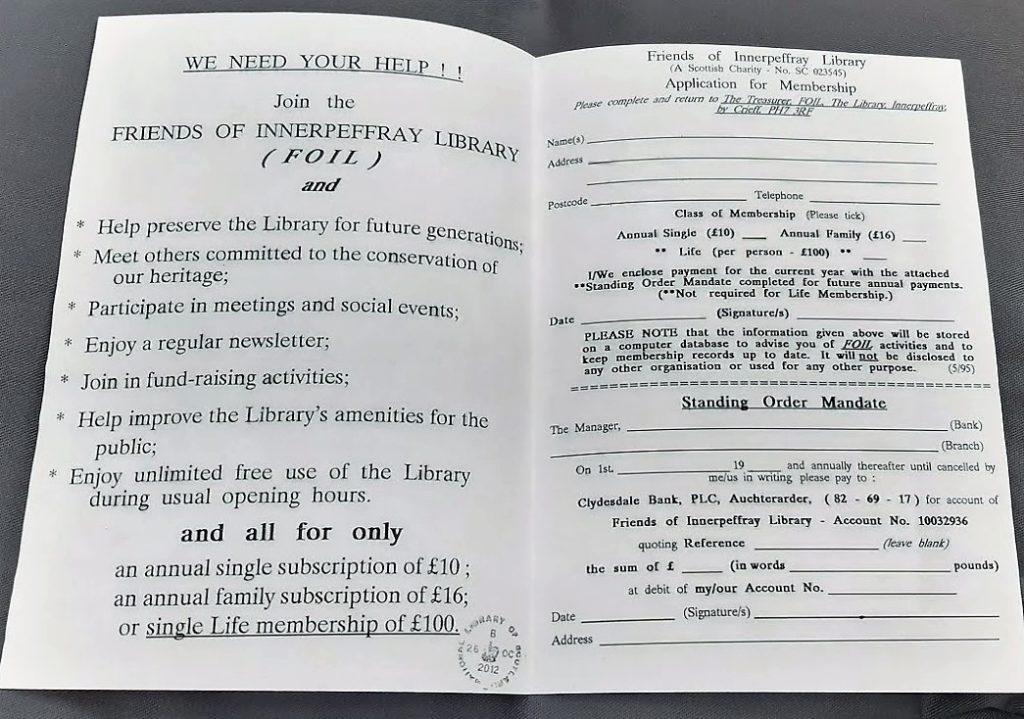

Engraving of William Drummond of Hawthornden

William Drummond of Hawthornden.

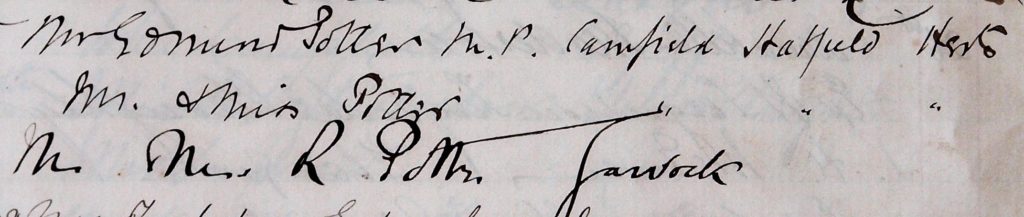

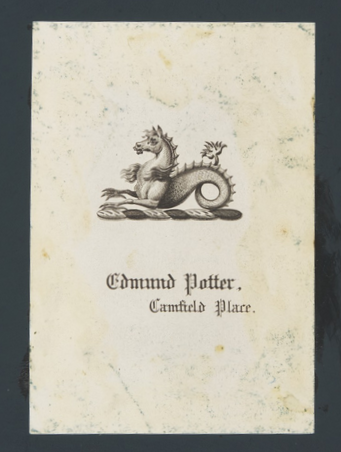

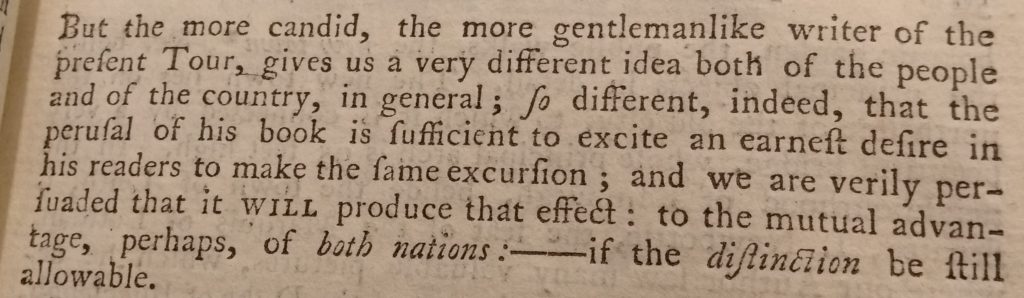

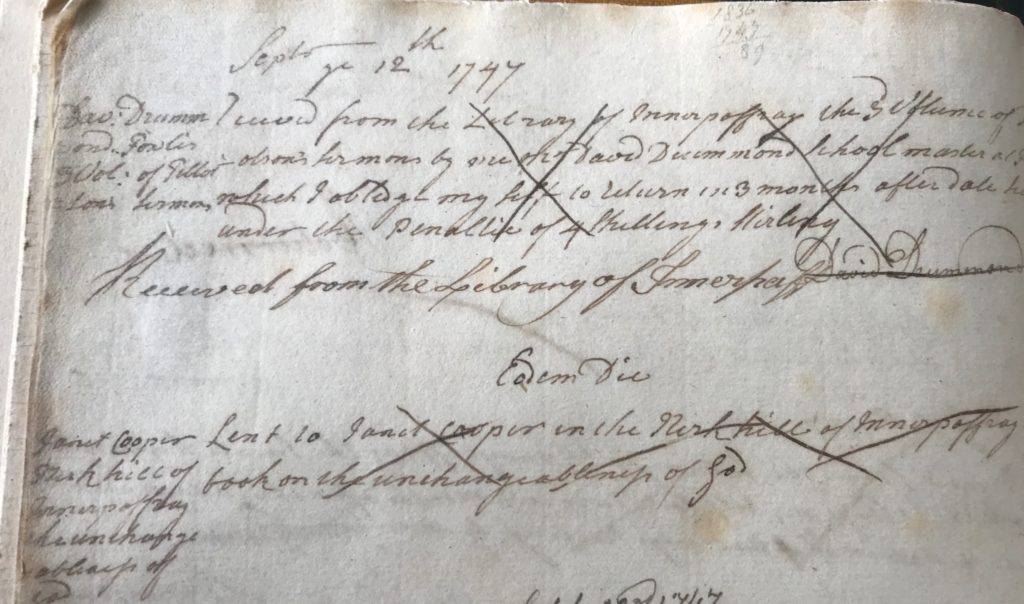

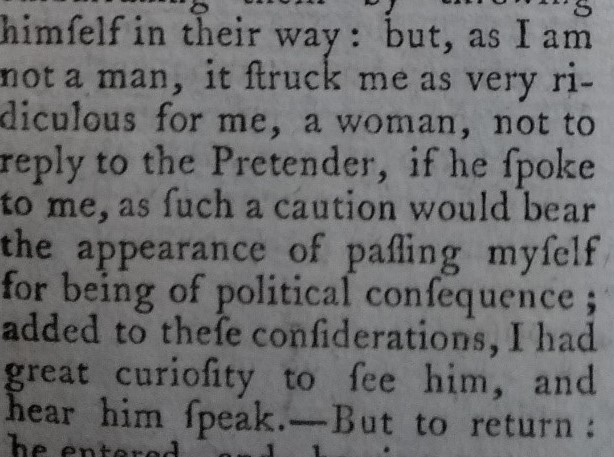

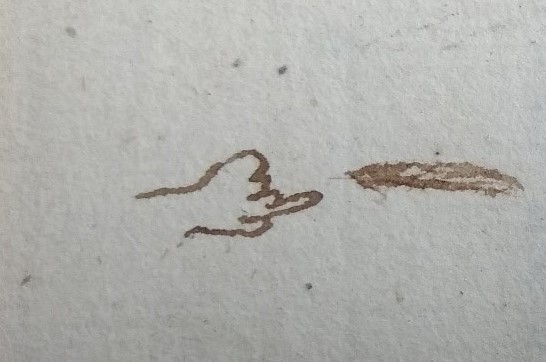

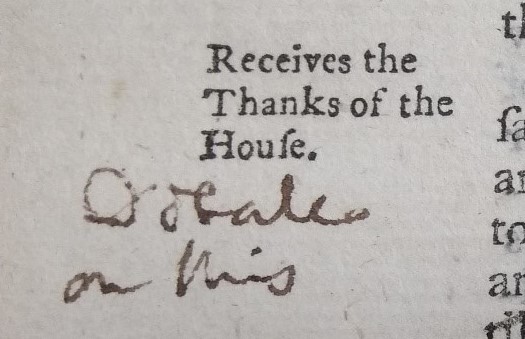

Jean Ann lamented the fact that we do not have any portraits of Lord Madertie, only examples of his signature in his books, as seen above. However, we do have a number of portraits of his “slightly older cousin, the poet and historian, William Drummond of Hawthornden from which I think we can deduce the general style and manner of Madertie’s appearance.”

William Drummond

In a similar vein, Jean Ann introduced the audience to William Drummond, the younger brother of Lord Madertie. While he was sadly uninvolved with the library’s foundation, due to his passing away, his portrait is proudly displayed in the library, and he provides a potential glimpse into the features of our founding father.

Robert Hay Drummond

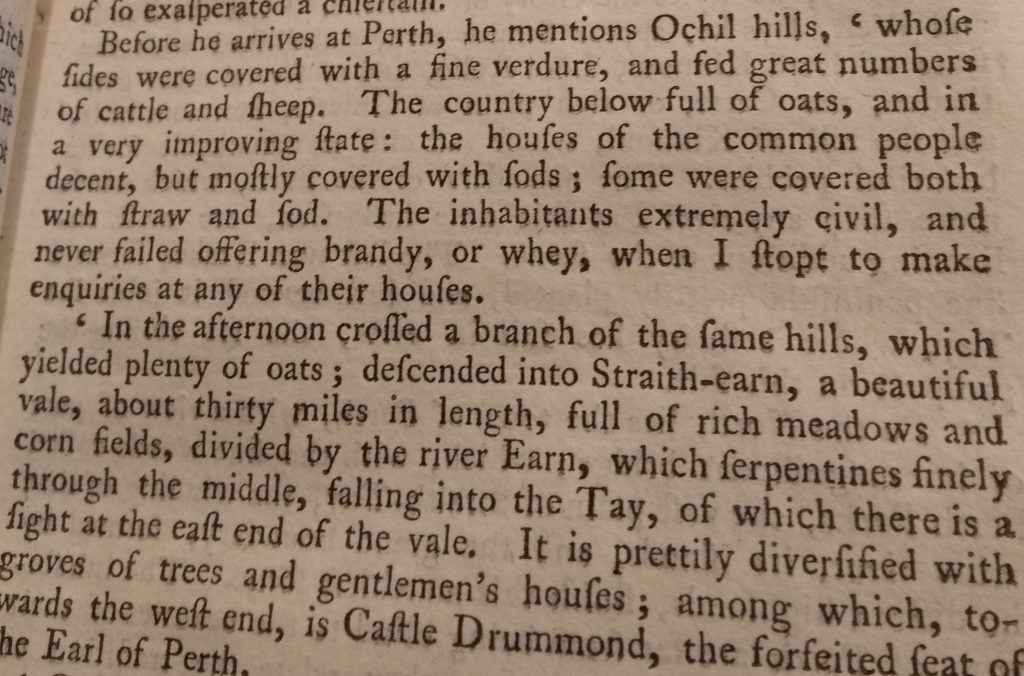

An exceptionally important Friend of the library, “He was born Robert Hay, a grandson of the 7th Earl of Kinnoull, and added Drummond to his patronym when he inherited the Innerpeffray estate from his great-grandfather, William Drummond, 1st Viscount Strathallan. His distinguished career culminated in his appointment as Archbishop of York in 1761, and he is hugely important for us because it was he who financed the building of the Library, begun in the 1740s and completed in 1762. He also donated and bequeathed a number of his own books to the Library, and even more important, made provision for the purchase of new books, the foundation of our outstanding collection of 18th century titles.

Arthur Hay Drummond

Next, Jean Ann introduced the audience to Arthur Hay Drummond, a man “generally credited with setting the Library’s affairs in order by updating the Mortification Trust… in 1853 at a time when the Library was in considerable difficulty.” While the majority of the work to establish the administrative change to the Library was conducted by Arthur’s older brother, yet another Robert Hay Drummond.

it is Arthur who is credited. This comes as a result of Robert’s untimely death at the age of 24, after succumbing to mortal injuries on his journey home from the Crimean War.

Having established the long history of the people whose investment and friendship towards the Library of Innerpeffray sustained the institution for centuries, Jean Ann brought us into much more recent times, with Friends from the 20th and 21st centuries.

Janet Saint Germain

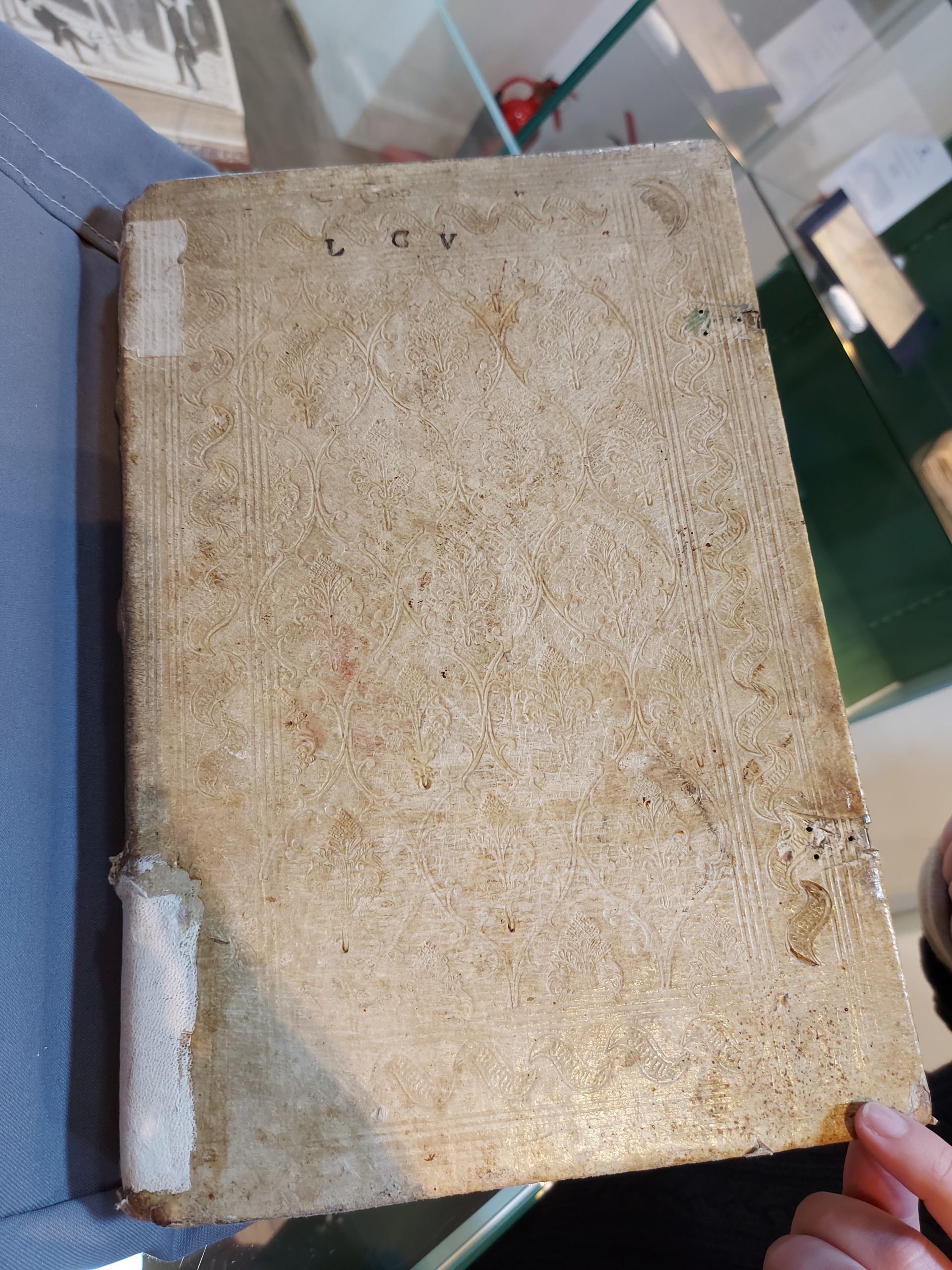

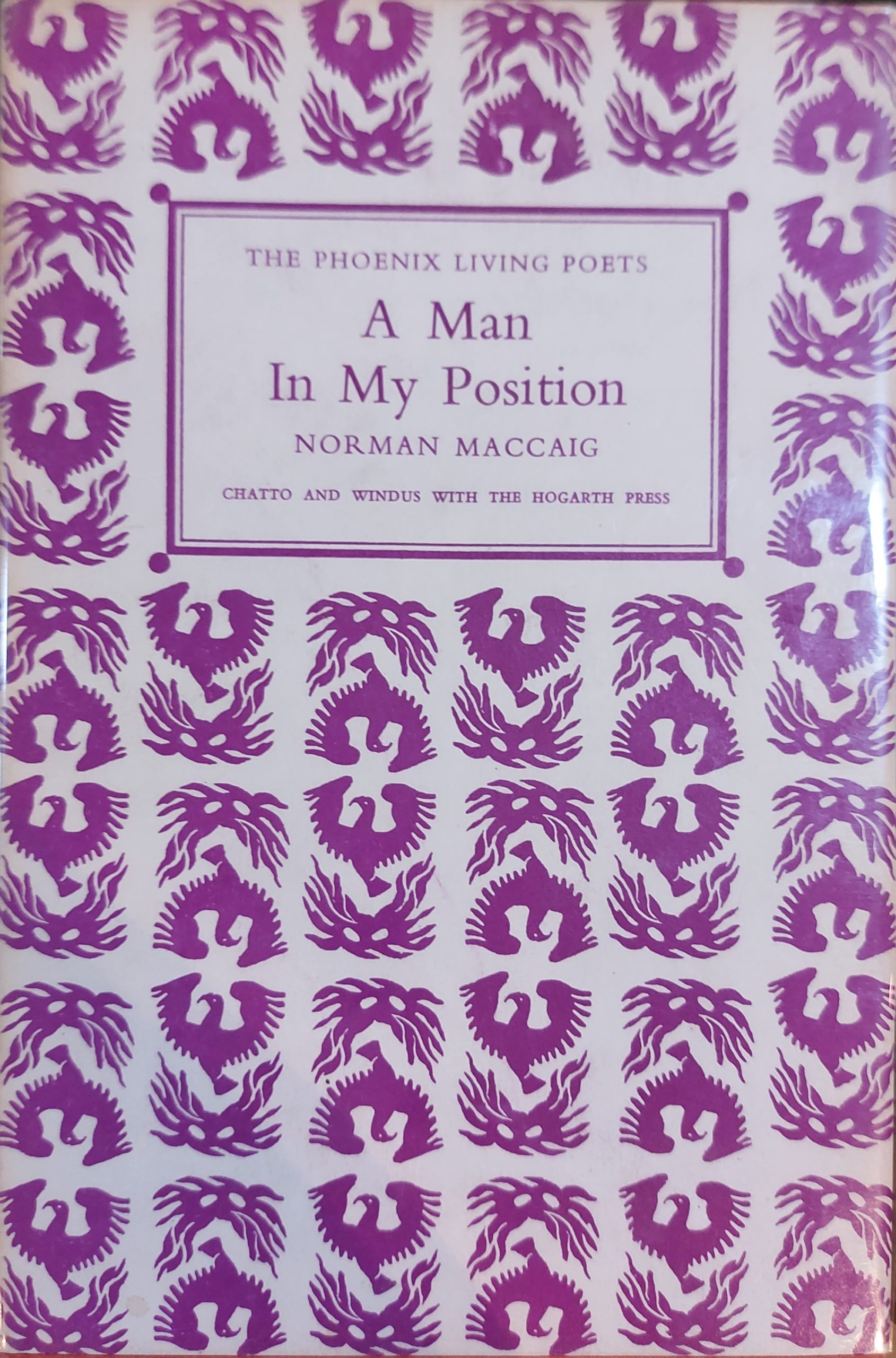

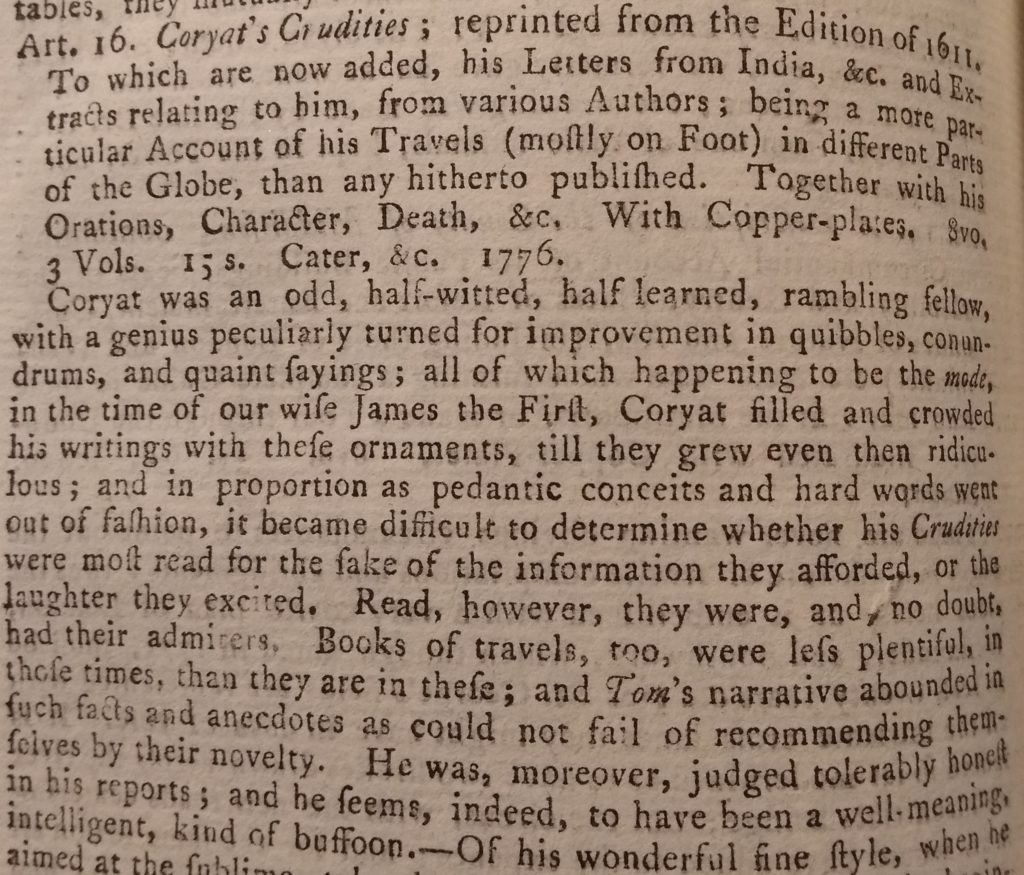

Another familiar name for those already versed in the Library’s history, Janet Saint Germain is one of our most important recent patrons. “Janet’s amazing gift of her collection of Scottish first editions, including the earliest books in the Library – a 1476 edition of the works of John Duns Scotus, the 13th century Scots theologian and philosopher – and extending to the 20th century renaissance of Scottish literature has given new life and lustre to the Library.” Janet Saint Germain’s bequeathment of these books in 2013 introduced a wealth of resources to the Library and allowed for the renovation of the downstairs of the building – leading to a beautiful set of shelves being added to house the collection. Janet sadly passed away in 2018, but her legacy and unfathomable generosity lives on in the Library.

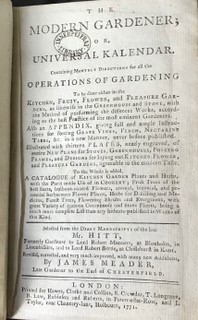

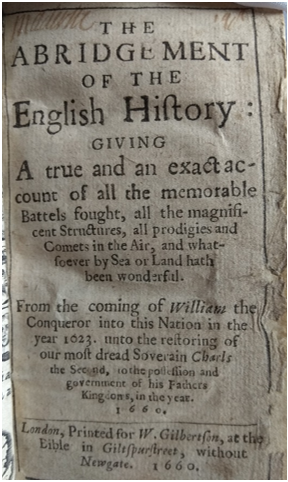

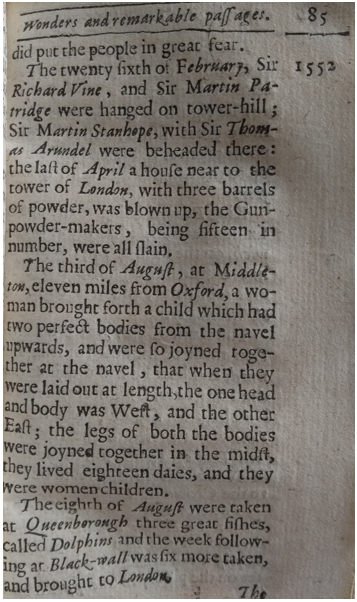

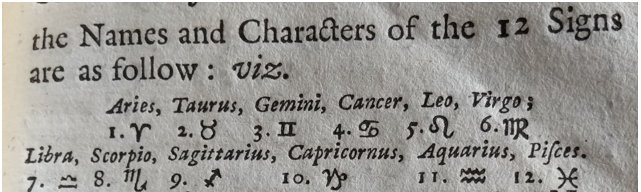

Left: Cover of Questiones in quattuor libros Sententiarum, John Duns Scotus, 1476

Right: Cover of A Man in My Position, Norman MacCaig, 1969

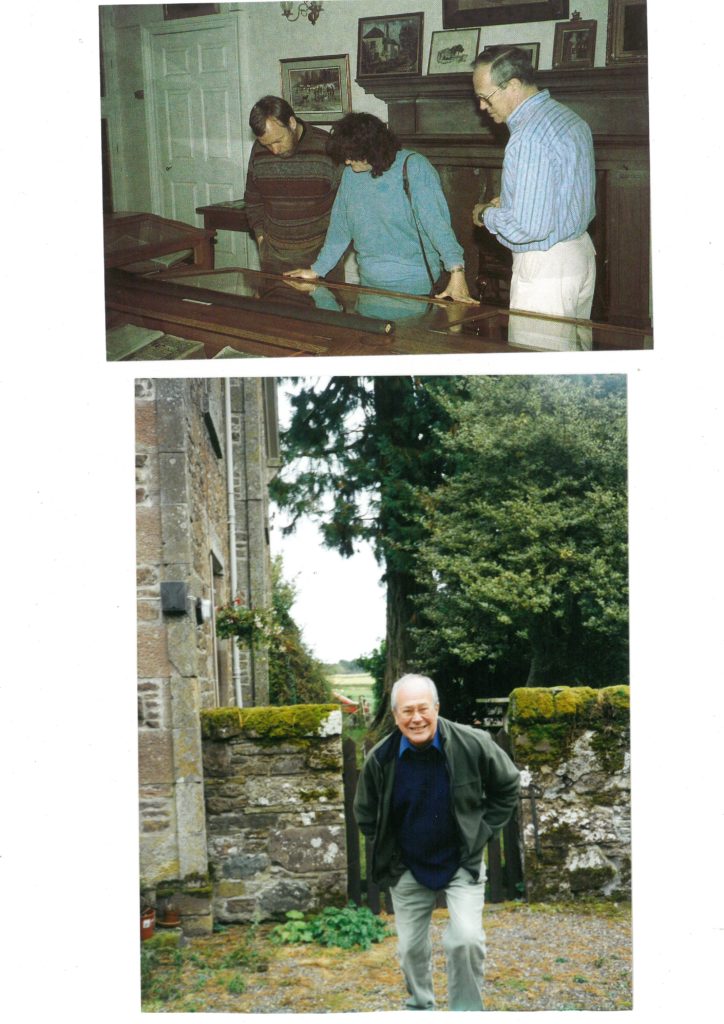

Bobby Wallace

Mr Wallace, a long-standing Friend of Innerpeffray Library played a large part in finding and securing funding for the Library throughout his time with us, and it was his “single-minded determination [which] secured the redevelopment of the lower part of the building to house [Janet Saint Germain’s] collection.”

It remained clear throughout the talk that there have always been people who have been devoted to the Library of Innerpeffray and whose time and efforts have kept the Library going since 1680.

Jean Ann continued:

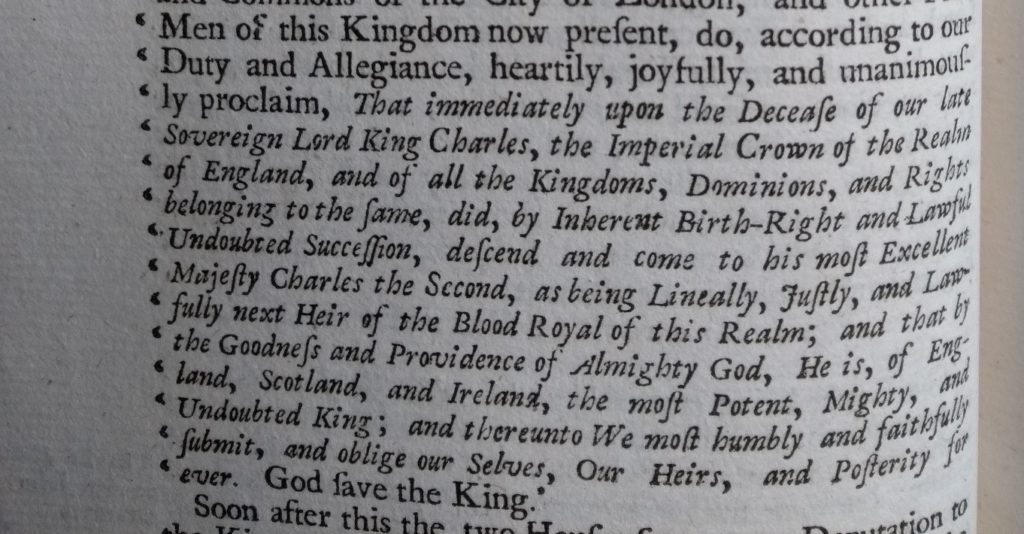

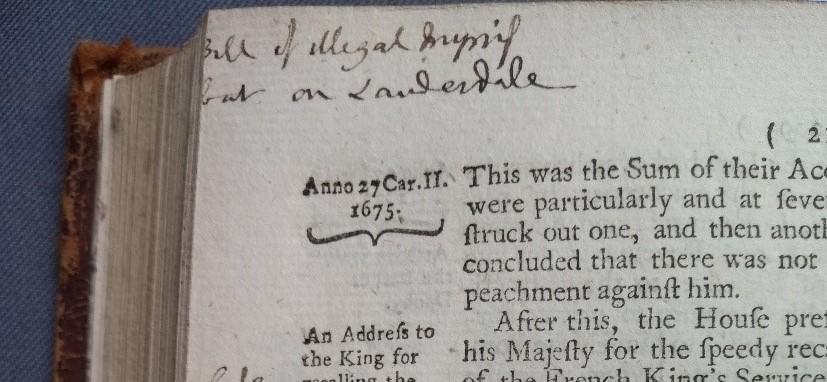

“We’ve almost arrived at FOIL, but again we must first understand a little about the Library’s instrument of governance, the Mortification Trust. Lord Madertie very plainly wanted the Library to continue after his death. He left it a considerable sum – 5000 Scots merks – in his Will, and also endowed land in its favour – possibly the present graveyard… but Lara [Haggerty] suggests… that it may have been a parcel of land from the estate which could have provided regular income. In any case, shortly after Madertie’s death in 1692, his surviving family established the Mortification Trust to ensure the Library’s continuation, and in the interests of that continuity, it was determined that there should be an enduring connection between the Library, the Haldanes of Gleneagles, and the holder of the Innerpeffray estate.” Over time this connection has adapted, and remained intact until 2019. At present, “the Mortification continues to fulfil its original purpose – to retain the collection in its historic setting to make it generally available to the public.”

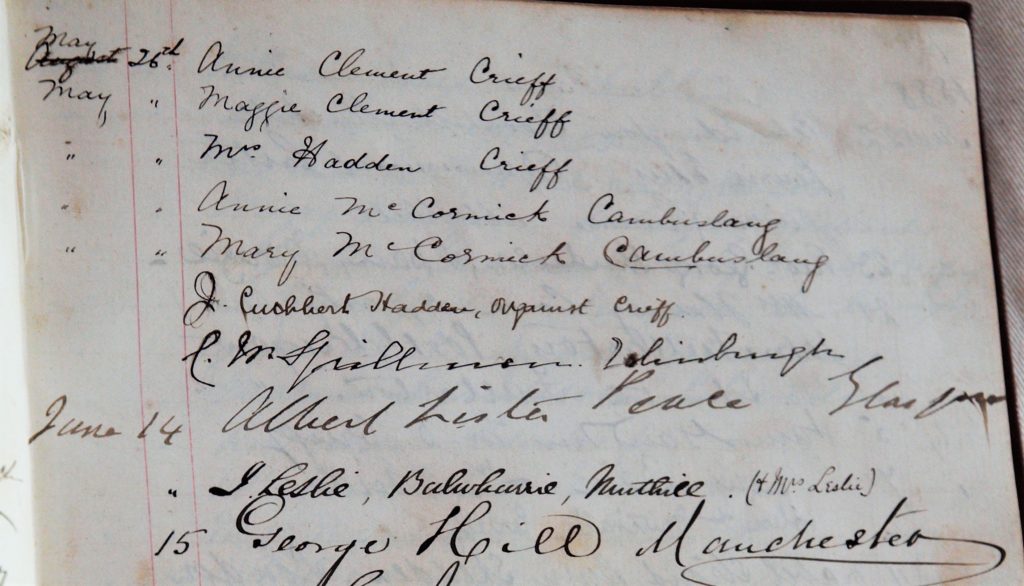

With the library ceasing to lend in 1968, due to evidently fluctuating use of the lending system between the 18th and early 20th centuries, it was unclear what would come next. The Library became a Book Museum, however “Matters came to a crisis point in the early 1980s.”

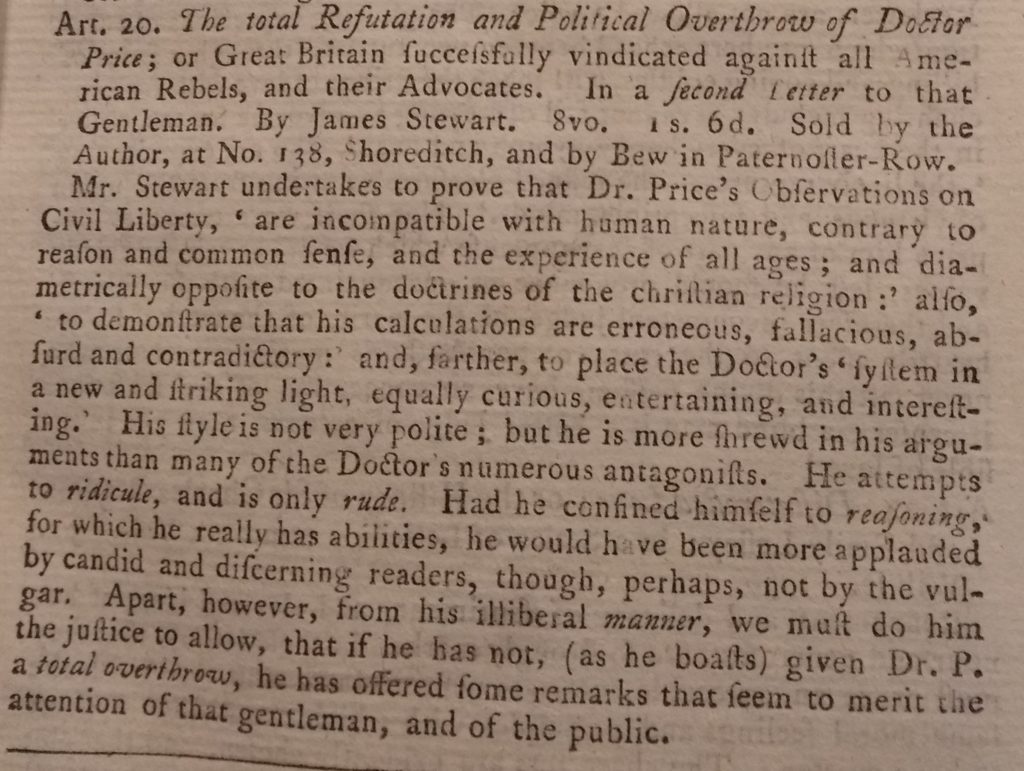

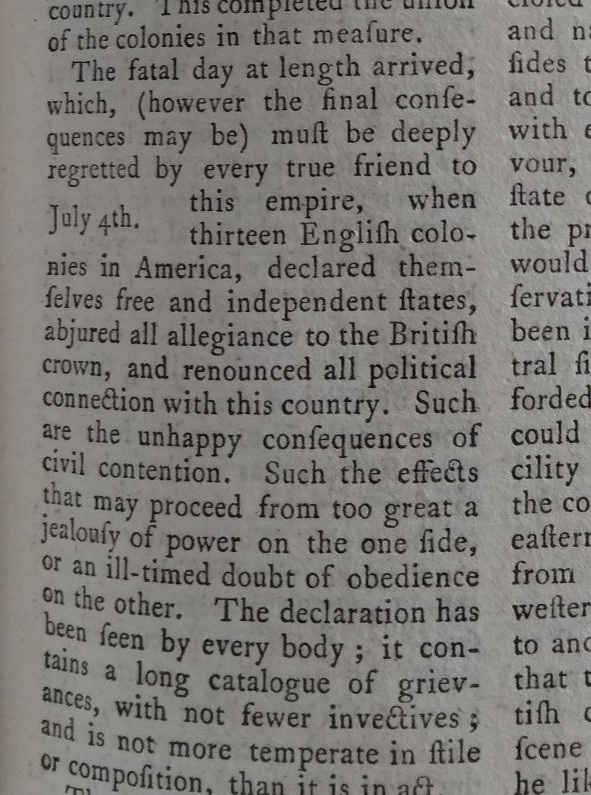

In 1983 there were discussions of transferring much of the collection to the National Library in Edinburgh, and potentially to hand the Library building over to the Department of the Environment – the latter suggestion being rebuffed by the Minister, Lord James Douglas Hamilton and eventually fruitless.

1988 brought a new lease of life to the Library with the appointment of Librarian Ted Powell, and the appointment of Frank Thomson as a Governor. Following swiftly, in 1992 Frank Thomson’s wife Lucie – an Independent on the Perth and Kinross District Council – became a representative on the Library’s Board of Trustees. The team of Ted and Lucie was joined by Logan Mitchell, and together the three became the first official Friends of Innerpeffray Library.

This move was not initially supported by the Governors, something that is all the more confusing when taking into account a letter included in the Mortification file from 25th February 1953, suggesting the foundation of a “Friends of Innerpeffray Library”.

Recounting her memory of the early days of FOIL, Jean Ann stated “Our first members were mostly recruited by Lucie calling on her many friends with an application form at the ready and the genial instruction ‘You do want to be a Friend of Innerpeffray Library, don’t you.’”

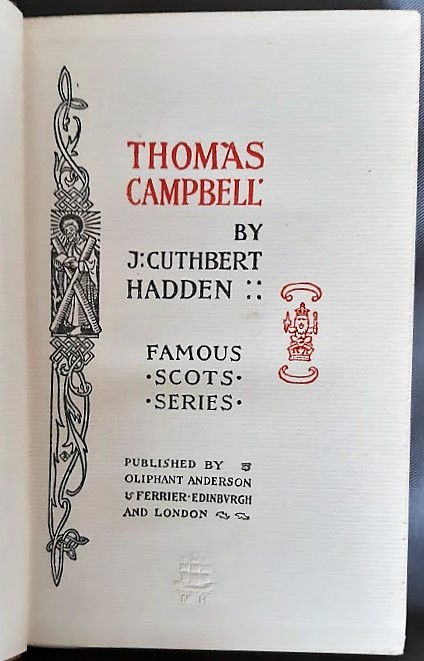

“A programme of monthly talks was quickly established. To begin with, most of the speakers came from the membership, and the talks tended to have a strong local or Perthshire interest. The pool of speakers gradually widened, as did their subject matter. We learned about cheese, and chocolate, and bees. About the men who built the Hydro dams and tunnels. About the Scots translation of Shakespeare’s Scottish play. About the Enlightenment – two very different views some years apart, one from Magnus Linklater… and the other from David Purdie… Other prominente joined our speaker’s list:… Willie Prosser, then Lord President of the Court of Session. He was followed, in no particular order by Sir William Macpherson of Cluny…; Lord Elgin; the Duke of Montrose; Sue Black; James Robertson; Jim Naughtie; Sandy McCall Smith; and most recently, Donald Findlay and Val McDermid.” Here, “Sandy McCall Smith” may be more well-known to readers as Alexander McCall Smith.

“Tony Murray adapted a fascinating Jacobite correspondence from the Dollerie archive into a dramatic reading. We heard about the construction of the V&A in Dundee; about Dundee’s mediaeval importance as one of the Baltic ports; about the Gask Ridge excavations; the Stone of Destiny; Tacitus’ life of his father-in-law Agricola; and on one exceptionally lengthy evening the branch railway lines of Upper Strathearn.” Jean Ann proceeded to outline the FOIL talks’ history of hospitality – with wine and nibbles being a foundational pre-talk tradition continued to this day, often due to the generosity of FOIL members.

“A FOIL newsletter was also quickly established, initially edited – and largely written – by Logan Mitchell… Under Maureen Nicholson’s later editorship, it continued to give the members a lively view of our activities, with the occasional submitted article.”

Musical and dramatic events have also been a staple of FOIL activities throughout the years. “A group from Kirriemuir… gave us a recital of Lady Nairne’s Jacobite songs. Peter Davenport brought his jazz band. The Really Terrible Orchestra came from Edinburgh. Crieff Drama Group performed excerpts from Shakespeare. Jess Smith gave us an evening of songs and stories. We had recitals From Chansons and from the Roseneath Singers. And in 2000, the first Carols at Innerpeffray started a Crieff Christmas tradition, with the Innerpeffray Singers under their founder and conductor Joan Taylor.”

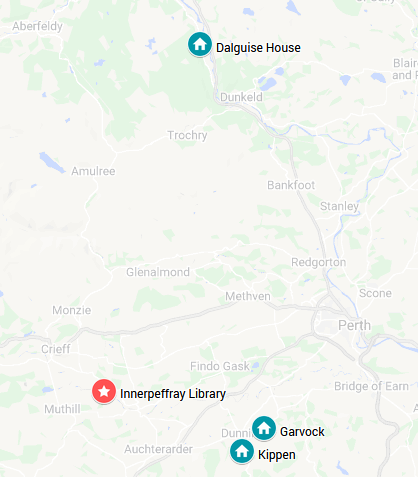

Jean Ann also detailed the various trips that FOIL undertook, including visits to Monzie Castle, Gleneagles, Arniston House, Balcarres, Newton Castle, Ardvorlich, and Drummond Castle to name a few.

Most importantly, the charity achieved its chief aim: raising money for the Library. In the six years between 2007 and 2013, FOIL gave £68,150 – through a mixture of direct donation and also money spent on projects for the Library. Improvements have been made to the Schoolhouse connected to the Library, which houses many events and is a modern manifestation of the school that was also built by David Drummond, Lord Madertie. Three state-of-the art exhibition cases now sit in the ground floor of the Library, costing £13,211 and partly funded “by a very generous bequest from Irene McKechnie – she and her husband Ken were founder members of FOIL…”

“Another even more generous bequest from Dr Vera Coutts has since funded the improvement and extension of the car park and the installation of the external lights between the car park and the Library.”

“The very first of our projects was actually carried out free of charge. My husband [Jack Scott Miller] provided a second-hand Zip water heater for the Library loo, and Ray Baird fitted it.”

Throughout the talk, it was evidently clear that the passion, dedication, kindness and generosity of the members of FOIL over the past thirty years has not only kept the Library in incredible condition, but has also allowed the Library to adapt to the leaps and bounds of modernisation, keeping the books protected with the latest technology and allowing Lord Madertie’s vision to remain by preserving these incredible resources to be handled by visitors and volunteers alike.

Jean Ann concluded with the following:

“And that, Friends, is the answer to the question ‘Why FOIL?’ I hope this canter through most of our first 29 years of life will encourage all FOIL members here tonight to renew their subscriptions on time, to support the Committee by attending talks, events, and outings, to bring visitors to the Library and to encourage membership, and that any non-members will pick up a membership form and join. It is not over-egging the pudding to say that without FOIL, the Library could well have been lost. FOIL still has a vital role.

There’s something to add – “Being a Friend of Innerpeffray Library” means something else. It means using the Library as Lord Madertie meant it to be used. It means going to the Library and learning about the books and from the books. There are several ways to start this process. You can step through the door, turn yourself three times in a clockwise circle, point at the nearest book, and see what hares is starts running.”

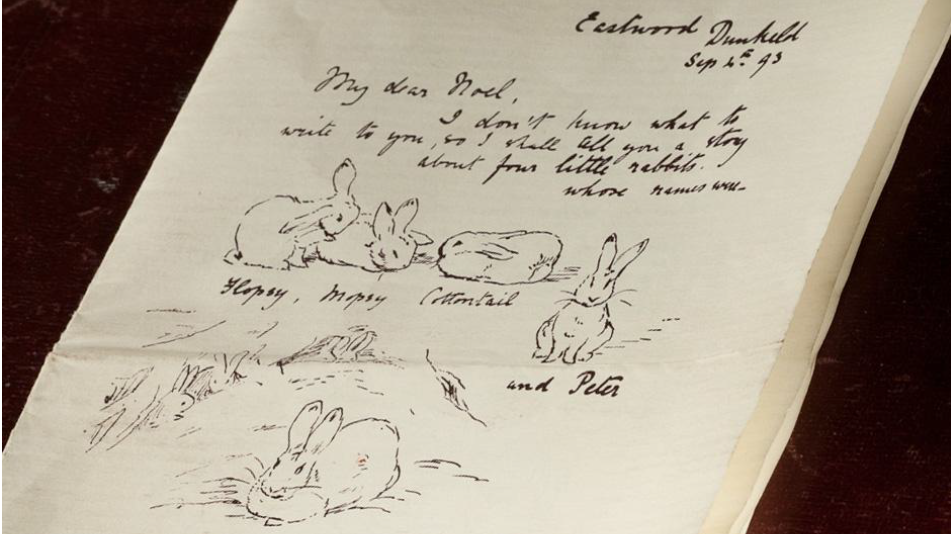

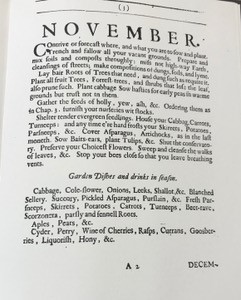

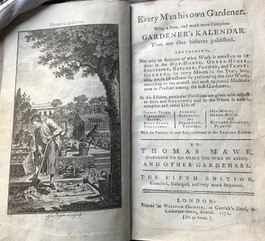

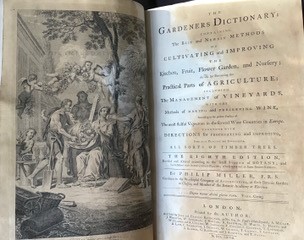

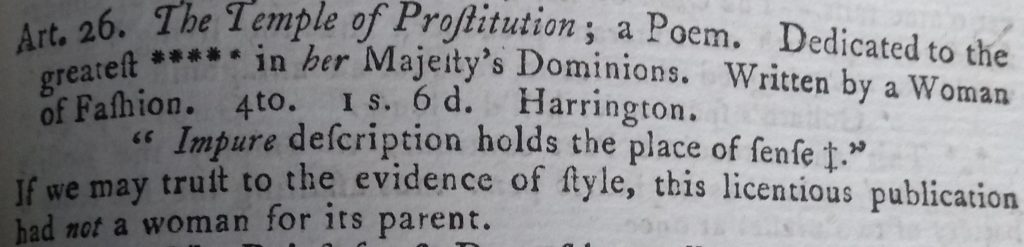

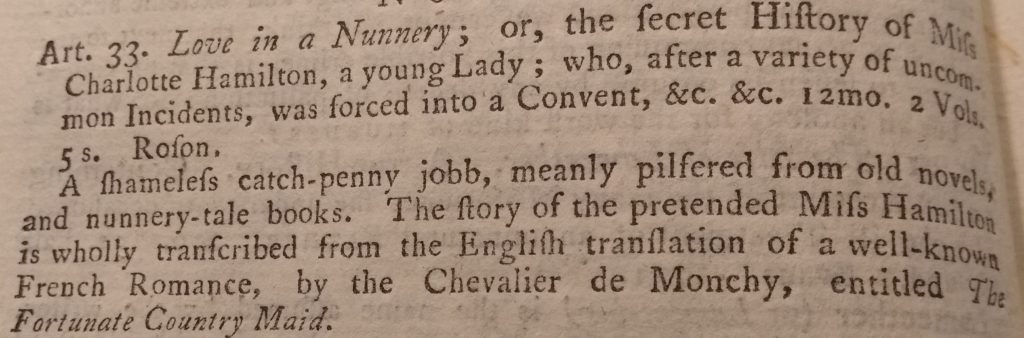

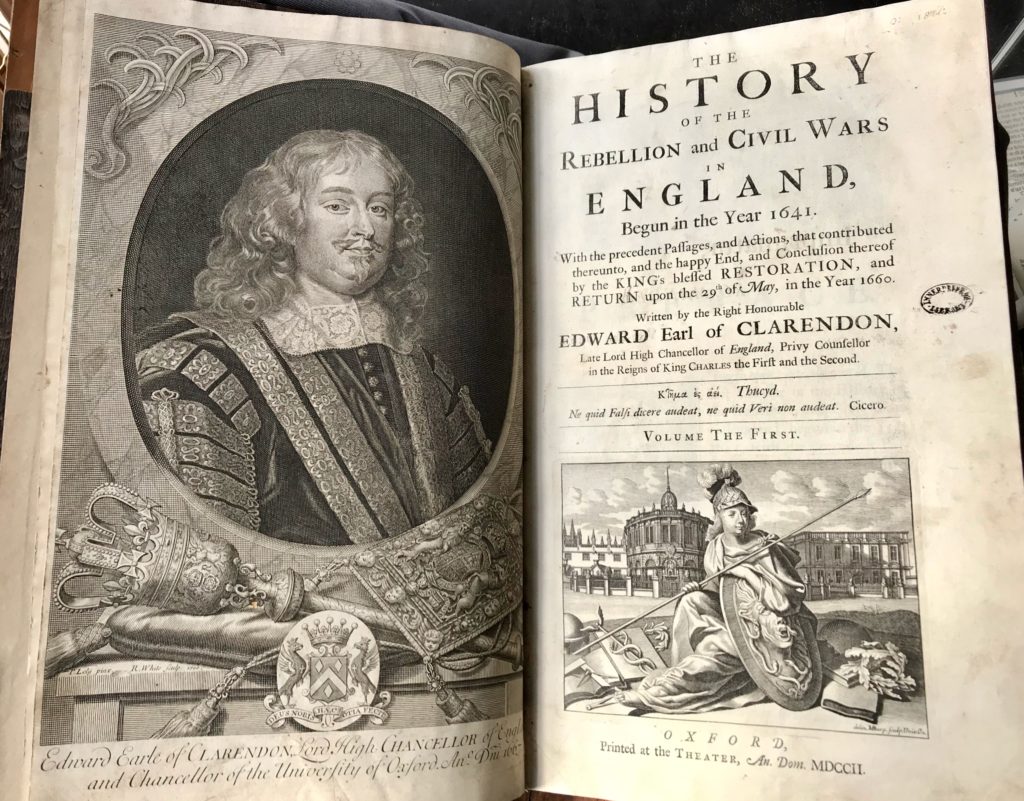

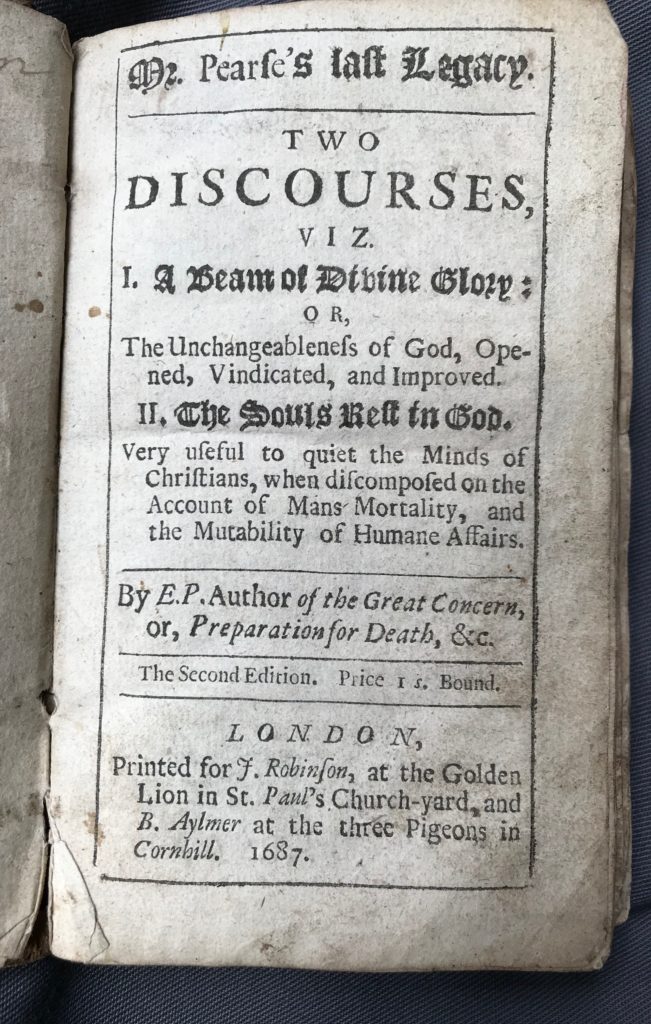

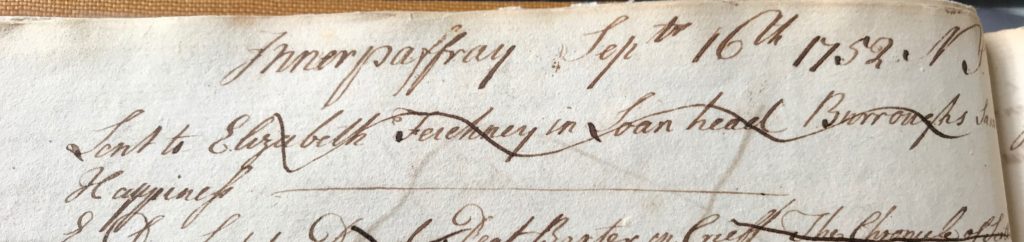

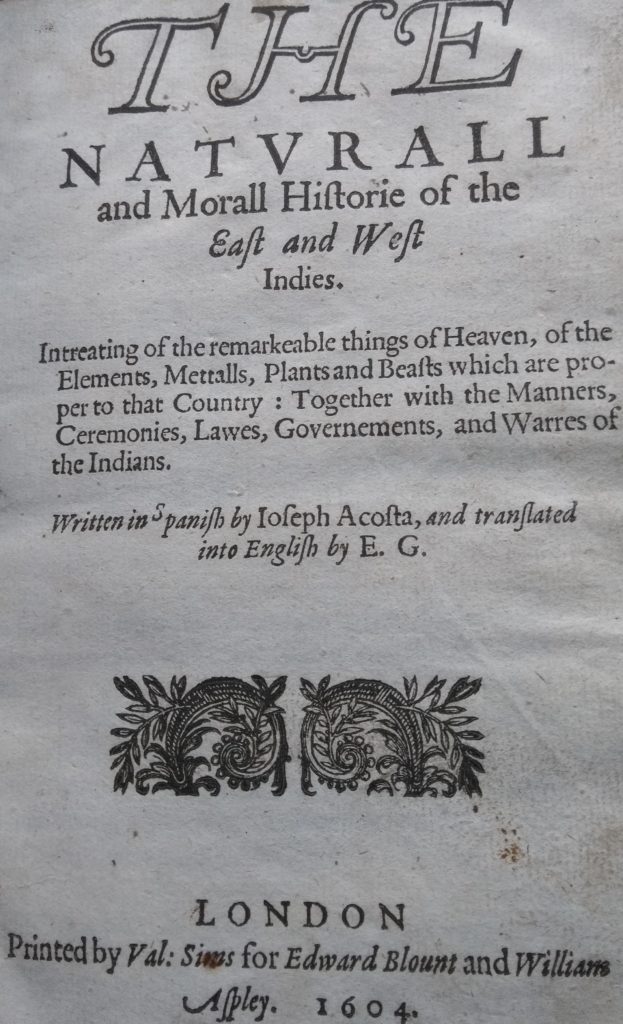

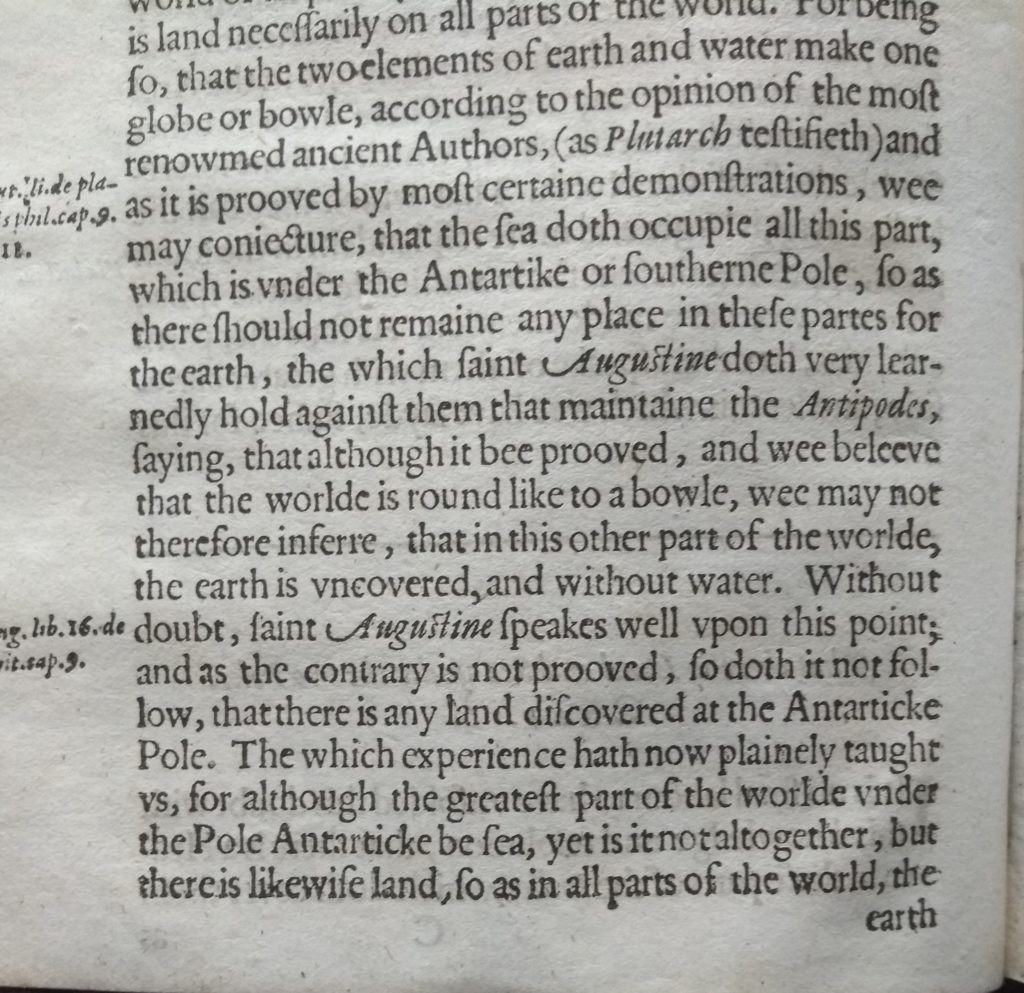

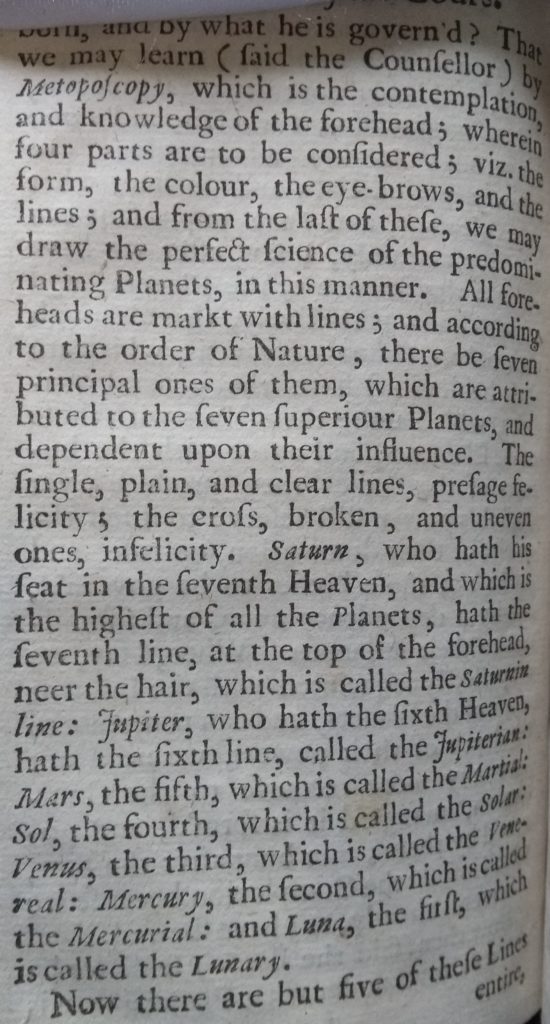

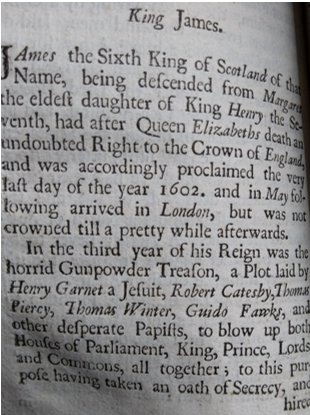

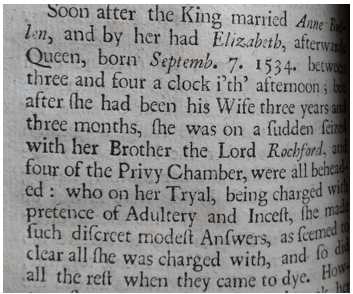

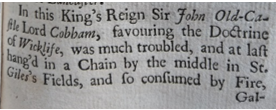

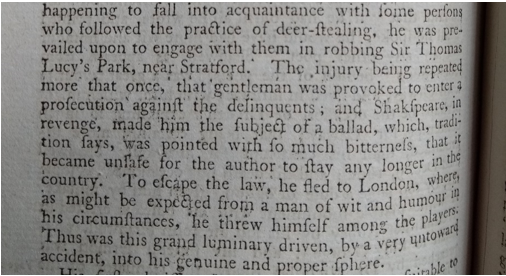

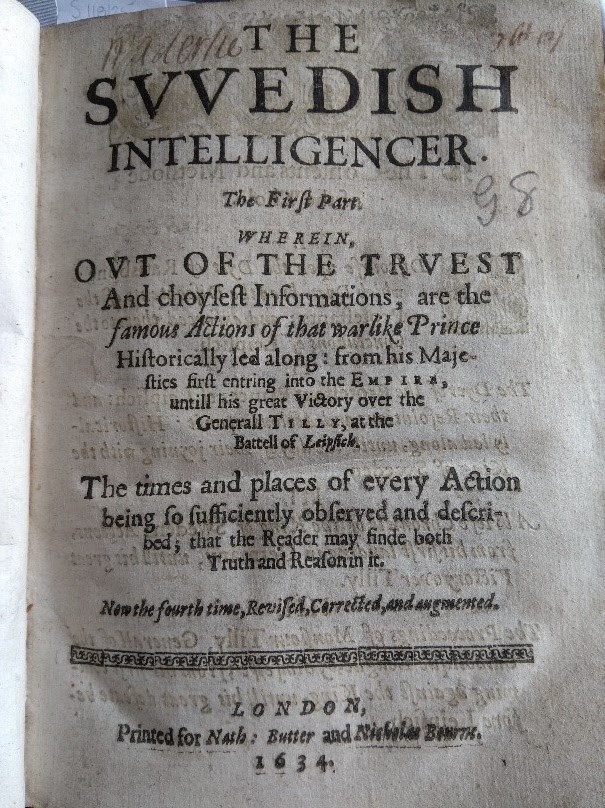

Throughout the talk, Jean Ann highlighted a number of incredible books that hide away in the vast shelves of the building; their secrets bound in brown and beige leather, while their weathered pages call out to be touched and turned, the black swirls of countless different fonts enticing visitors to dive into infinite realms of discovery. A bibliography has been compiled at the end of this blog for the interest of readers, should you seek a place to begin with your visit.

Special thanks go to Frank Thomson and Louise Powell for providing photographs. John Hughes provided the figures regarding funding. Lara Haggerty, Keeper of the Books; Naomi Harvey, Assistant Keeper of the Books; and volunteer Gillean Ford provided a number of supportive facts. Sophie Wood compiled the presentation and provided technical support on the night of the talk.

Most of all, thanks go out to the audience members who attended the talk, members of FOIL whose continued support sustains the Library of Innerpeffray, and to you, the reader, who even in reading through our history and engaging with our website provides another layer to our story and allows us to reach an even wider audience.

Having had the privilege of working alongside Jean Ann Scott Miller and all of the Library staff, I have learned so much about the foundation of the Library of Innerpeffray, and the Friends of Innerpeffray Library Charity. At the end of this talk, the question that stayed with me was not “Why FOIL?” The question now remains: “Why not?”

For more information on how to become a Friend of Innerpeffray Library, please visit: https://innerpeffraylibrary.co.uk/friends-of-innerpeffray-library/

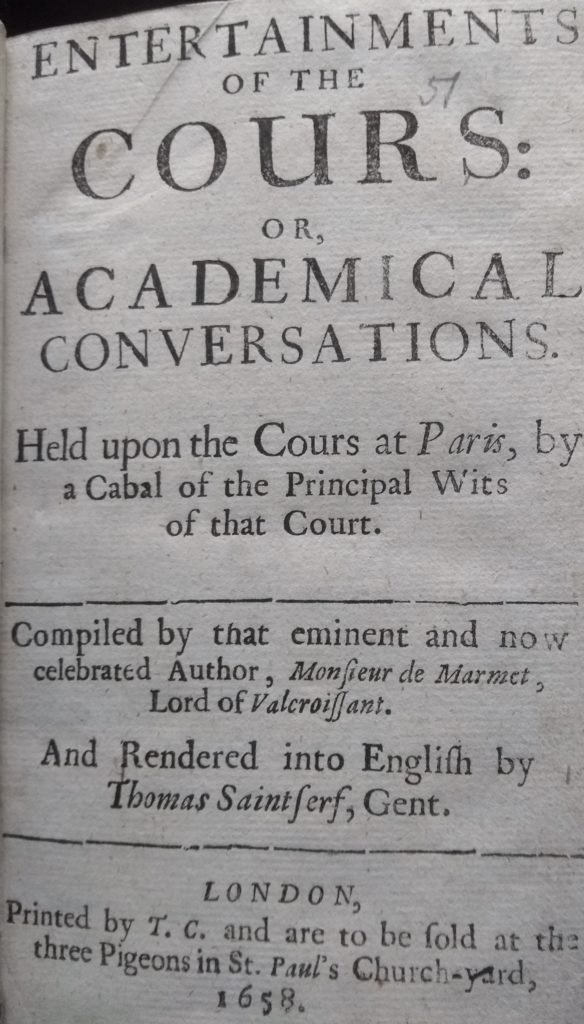

Bibliography:

Seven Good Reasons to join FOIL, Pamphlet, 2002-03

Portrait of William Drummond of Hawthorndern, in his The history of Scotland, from the year 1423. until the year 1542…, 1655.

William Drummond, Portrait

Some helpes to stirre up to christian duties, Henry Whitfield, 1634

Good thoughts in bad times. Together with good thoughts in worse times, Thomas Fuller, 1657

A vindication of the authority, constitution, and laws of the church and state of Scotland, Gilbert Burnet, 1673

The vvorkes of the most high and mightie prince, Iames by the grace of God, King of Great Britaine, France and Ireland, defender of the faith, James I, King of England, 1616

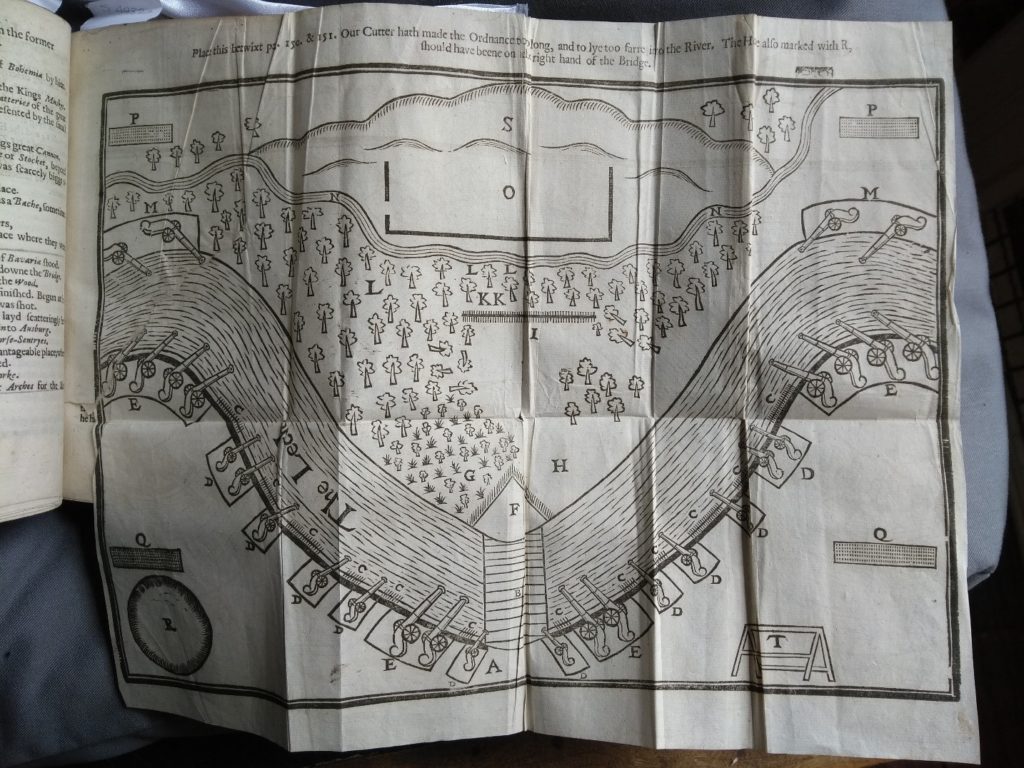

The history of this iron age: : vvherein is set dovvn the true state of Europe as it was in the year 1500, Jean-Nicolas de Parival, 1656

Medulla Historiae Anglicanae…, William Howell, 1681

Narrenschiff, Sebastian Brant, 1570

All the vvorkes of Iohn Taylor the water-poet: Being sixty and three in number, Elizabeth Allde, 1630

The pleasant history of Lazarillo de Tormes a Spaniard…, Diego Hurtado de Mendoza, 1639

The noble art of venerie or hunting, George Gascoigne, 1611

Kriegskunst zu Fuß…, Johann Jacobi von Wallhausen, 1620

An institution of general history, or The history of the ecclesiastical affairs of the world…, William Howell, 1685

La cosmographie universelle de tout le monde…, Sebastian Munster, 1575

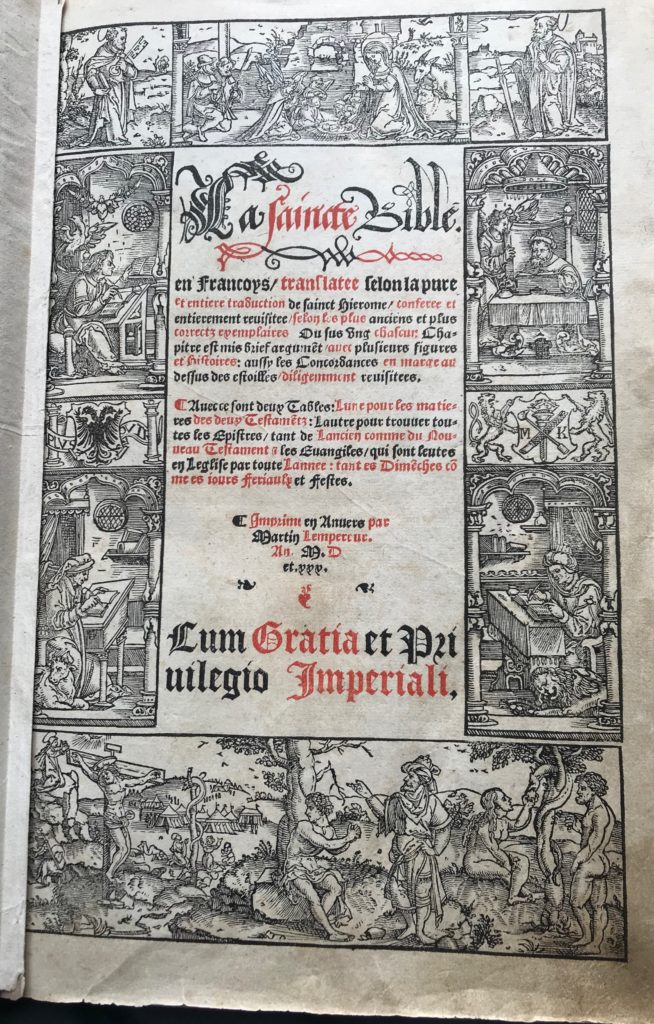

Les CL. Pseaumes de David, Bible, 1567

Speculum Mundi…, John Swan, 1635

Robert Hay Drummond, Portrait

South Exterior of the Library, Sophie Wood, 8th April 2022

Arthur Hay Drummond, Portrait

Christine Wallace, Janet Saint Germaine, Dr Alistair Kennedy, Robert Wallace, Photograph from Album

Questiones in quattuor libros Sententiarum, John Duns Scotus, 1476

A Man in My Position, Norman MacCaig, 1969

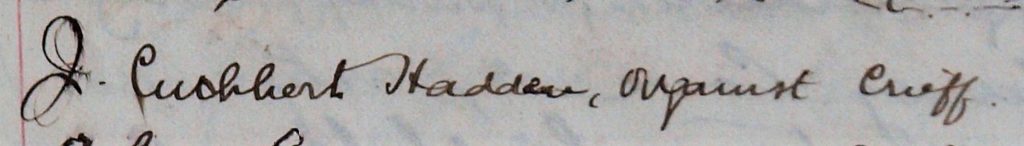

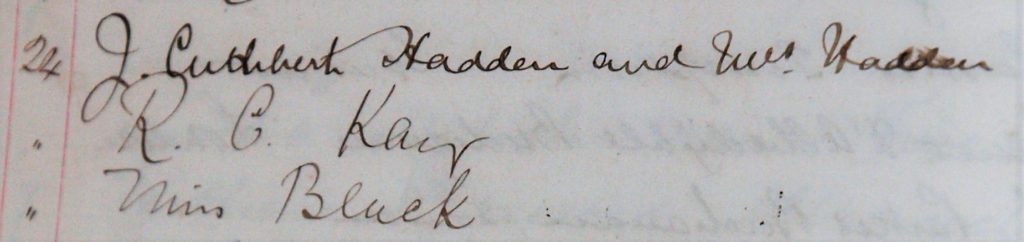

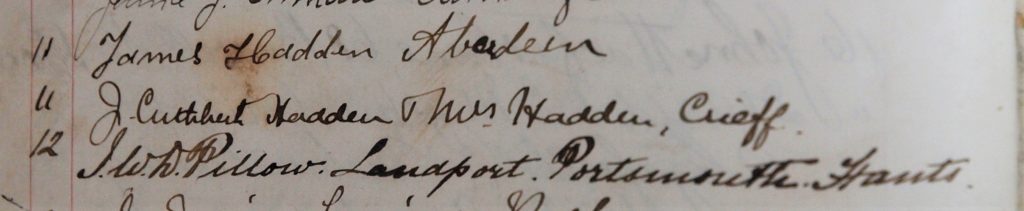

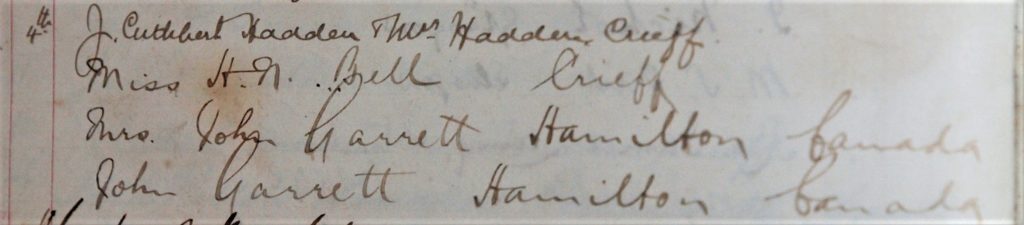

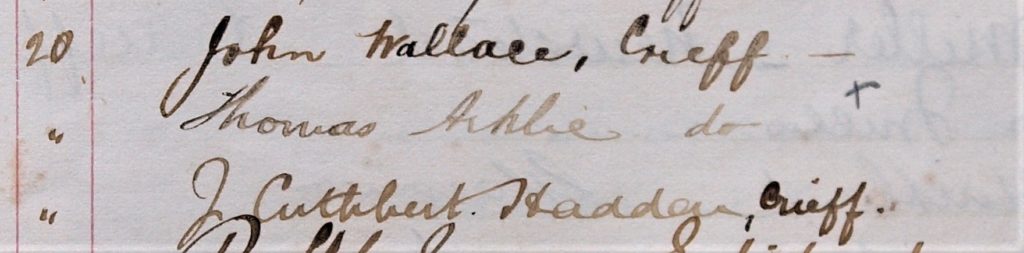

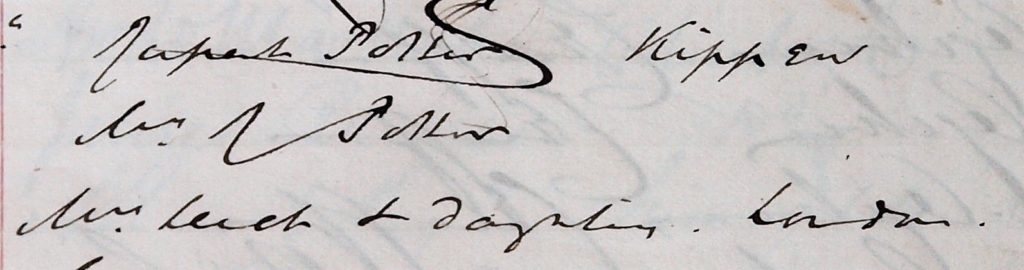

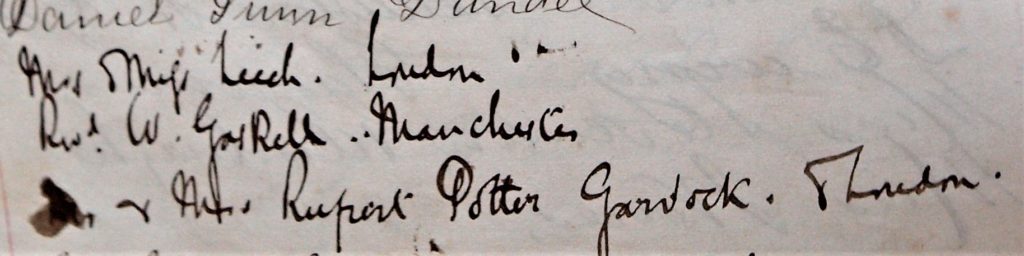

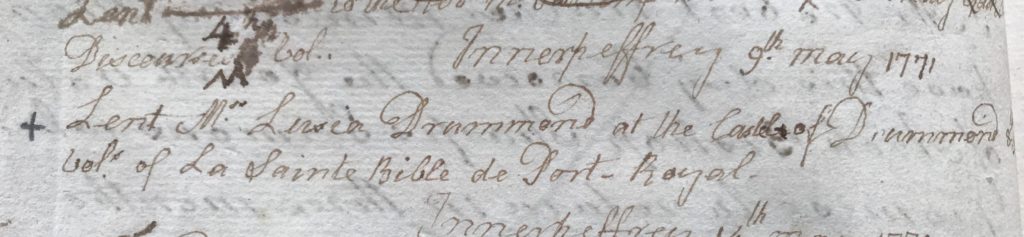

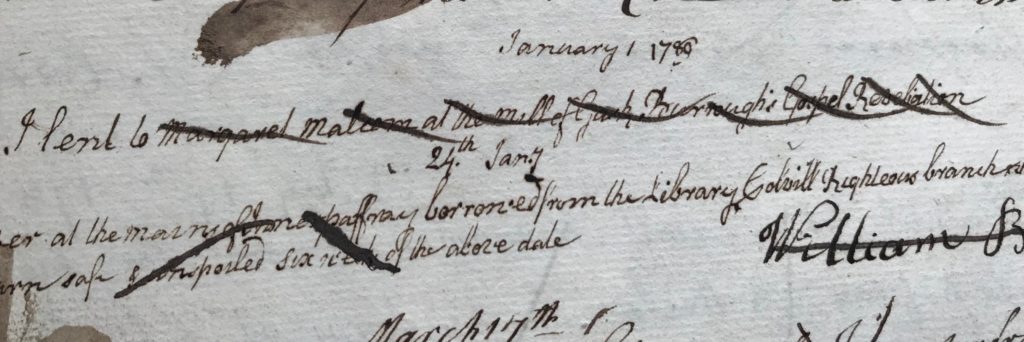

Innerpeffray Library register of borrowers, 1904

Mortification of Library of Innerpeffray, 1953

FOIL Facts, Newsletter, April 2000

New Artzney Buch, Christof Wirsung, 1617

Scotorum Historiae, Hector Boece, 1527

Scotorum Historiae, Translated by John Bellenden, 1540

The firste volume of the Chronicles of England, Scotlande, and Irelande, Raphael Holinshed, 1577

The lives and characters of the most eminent writers of the Scots nation…, George Mackenzie, 1708-22

The history of the affairs of church and state in Scotland…, Robert Keith, 1734

The history of Scotland : during the reigns of Queen Mary and of King James VI. till his accession to the crown of England, William Robertson, 1761

The history of the reign of the Emperor Charles V, William Robertson, 1769

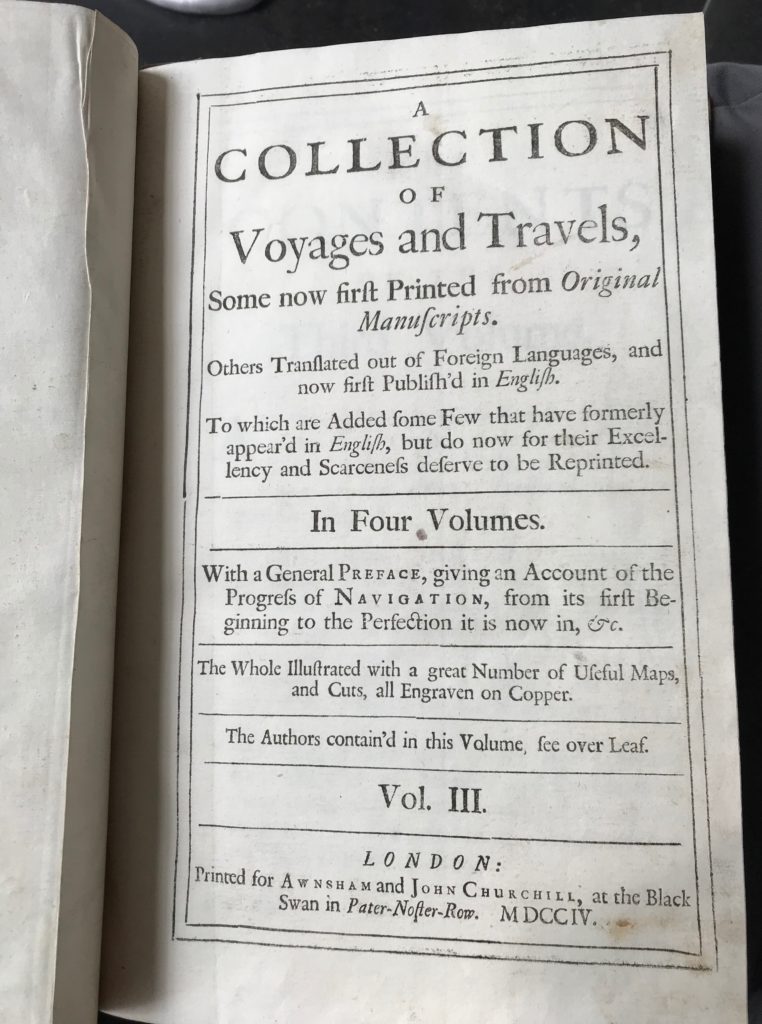

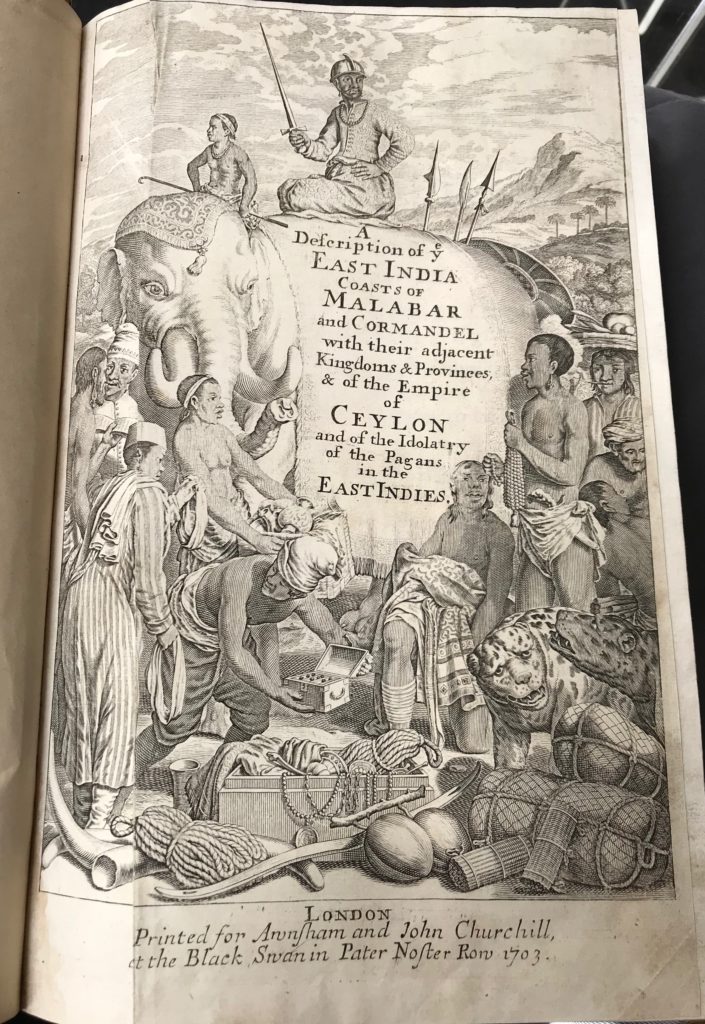

A collection of voyages and travels, some now first printed from original manuscripts, Compiled by Awnsham Churchill and John Churchill, 1704

A collection of photographs provided by Jean Ann Scott Miller, Frank Thomson, Louise Powell and the Innerpeffray Library Archive