Welcome back to our Visitor Vignette series, today focusing on Adam White (1817-1878), Zoological Assistant at the British Museum.

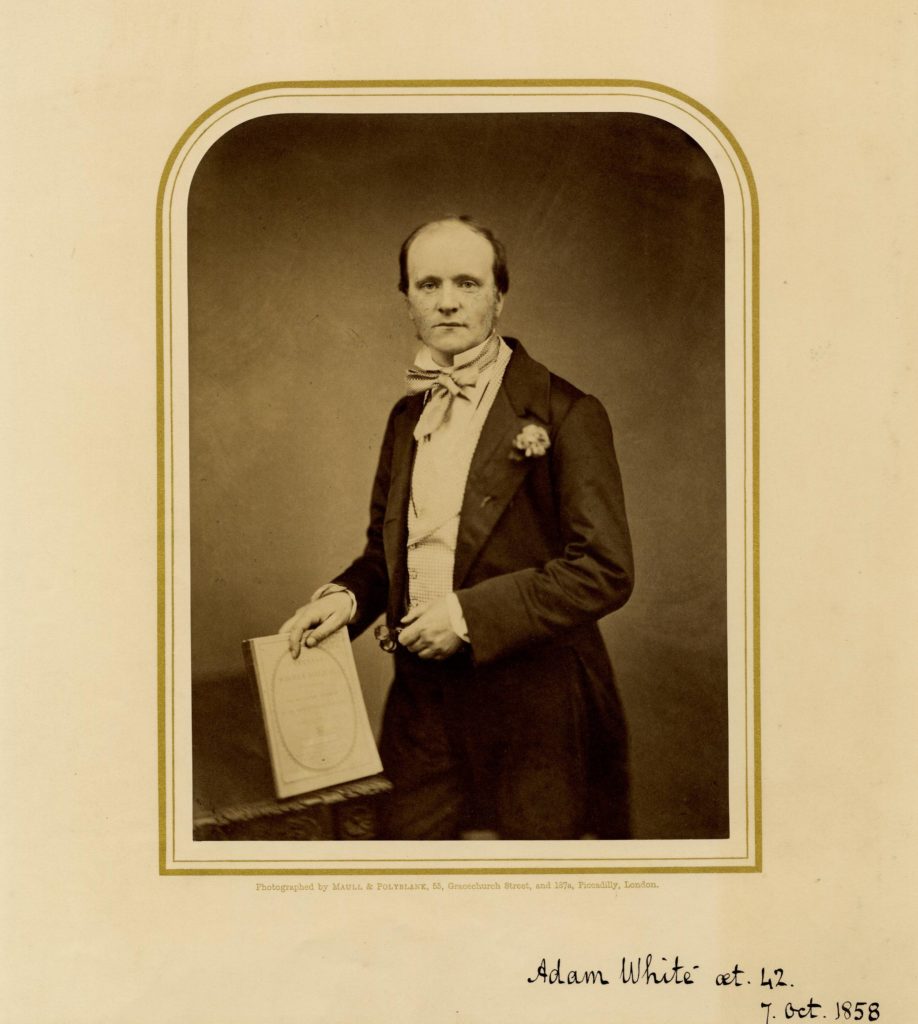

Photographed by Maull & Polyblank, 55, Gracechurch Street, and 187a, Piccadilly, London.

“Adam White æt. 42. 7. Oct. 1858” © The Trustees of the British Museum.

While the vast majority of entries in the Innerpeffray visitors’ books are purely factual (with limited details such as the date, visitors’ names, their places of residence and occasionally their occupations), there are a few extended entries which provide additional information and so enable exact identification of their author. The portrait above shows naturalist Adam White, aged 42, likely taken as part of photography firm Maull and Polyblank’s ‘Literary and Scientific Portrait Club’ series, which was issued in forty monthly parts from 1856-1859.[i] Although the book title is too faint to decipher, I imagine that White is holding either one of his own publications or another influential zoological text.

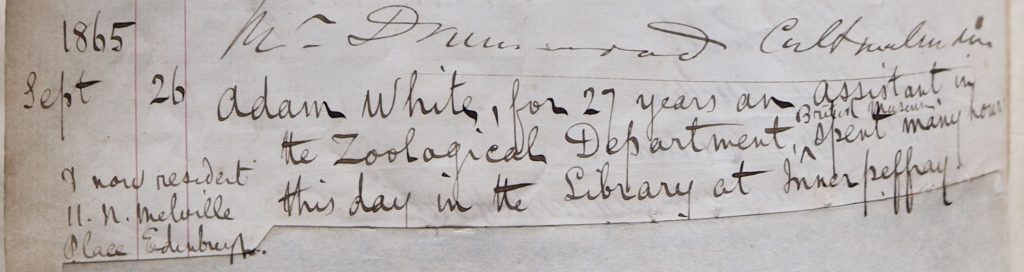

Seven years after this portrait was taken, on Tuesday 26th September 1865, Adam White visited the Library of Innerpeffray and inscribed a rare extended entry in its visitors’ book. In addition to his name and the date of his visit, White includes his past occupation, current address, and details about his visit to the library, revealing that he “spent many hours” there.

His entry, pictured above, reads: “Adam White, for 27 years an assistant in the Zoological Department, British Museum, spent many hours this day in the Library at Innerpeffray.” In the margin, underneath the date, he also adds, “& now resident 11. N. Melville Place, Edinburgh.” Had White only written a standard entry, with the date, his (fairly commonplace) name, and perhaps ‘Edinburgh’ as his location, it would likely have been much harder, if not impossible, to identify and discover more about him. But since we do have the extra information from his entry, we can actually find out quite a lot about Adam White – including details of a second visit to Innerpeffray within one of his written publications.

Although there is no trace of a second entry by him in the visitors’ book, we know that White visited the Library of Innerpeffray on at least two occasions. Published in the monthly periodical Good Words, White’s article on ‘Spiders’ reads:

“Come with me to that well-known point in Strathearn, called Whitehill, on an autumn morning. The sun is breaking through the mist, which conceals the lovely prospect all around. The view of the country, from the Ochils to the Grampians, from “fair” Perth to the woods of Strathallan and Drummond Castle, is spread out before you, but hidden. […] I was on my way to examine for a second time, the curious library of Lord Maderty at Innerpeffray, where are many books that belonged to the great Marquis of Montrose.”

Adam White, ‘Spiders’, Good Words, 7 (1866), 212-16 (p. 213).

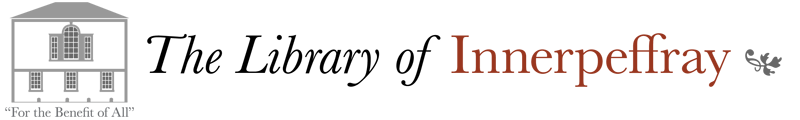

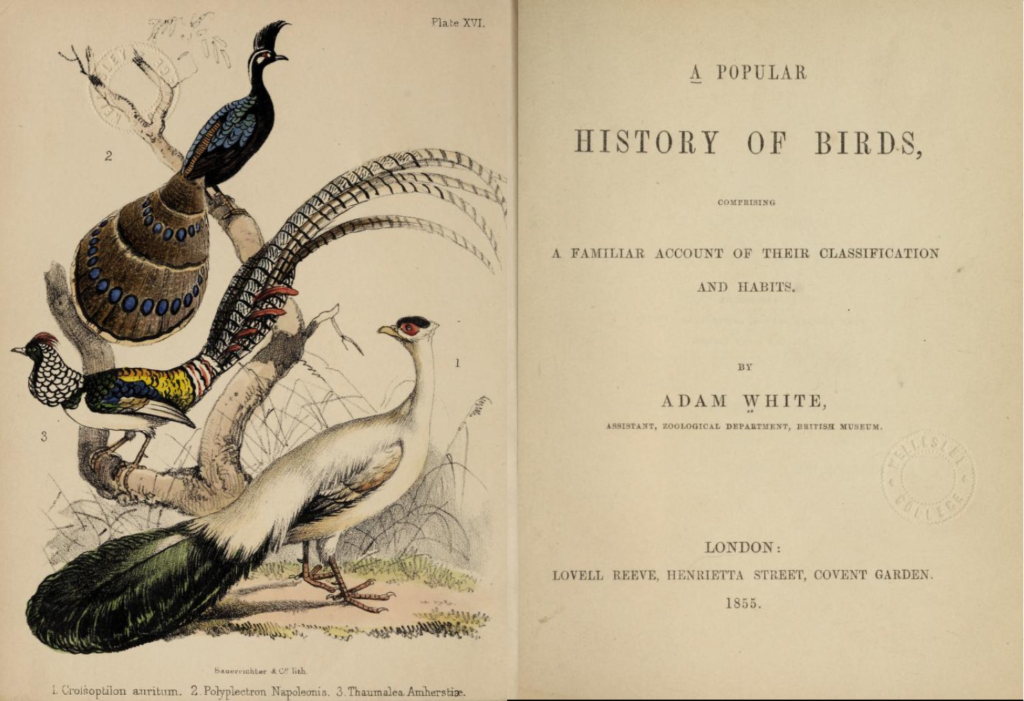

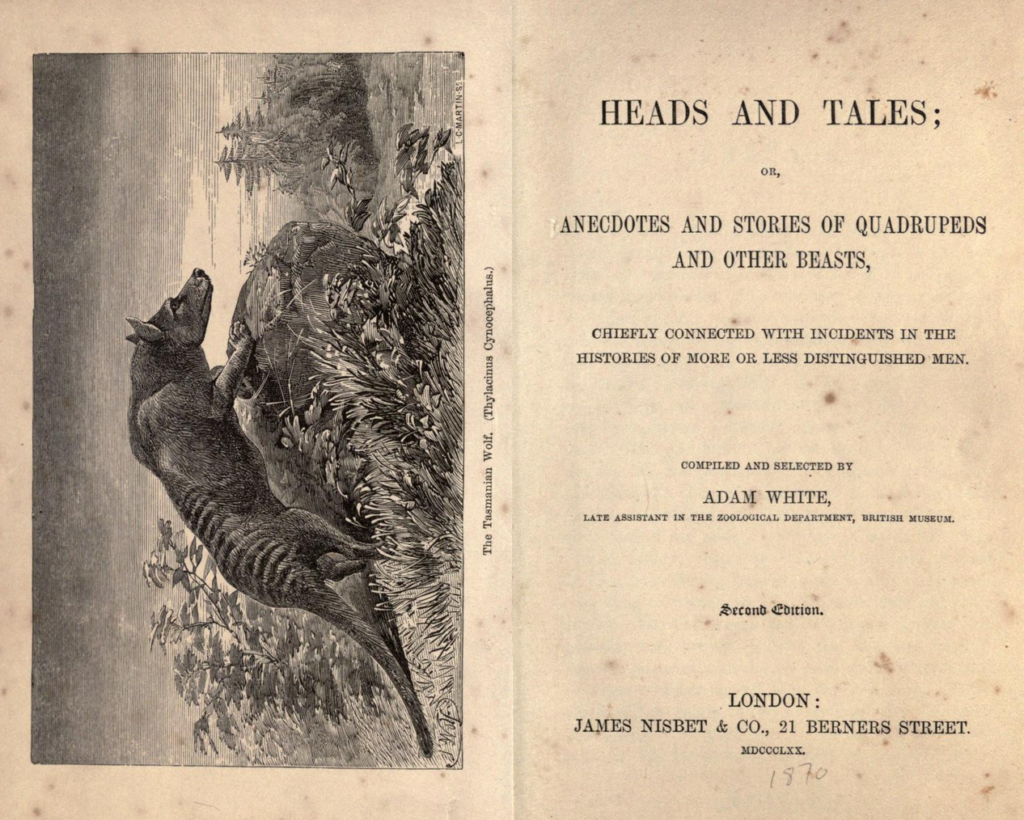

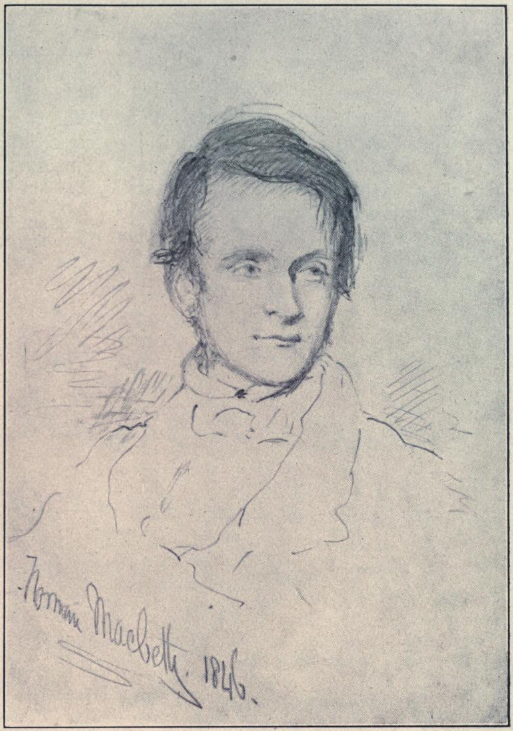

Born in Edinburgh on 29th April 1817 to Mary Ann (née Gellatly) and Thomas White and educated at Edinburgh’s Royal High School, our young Zoologist started work at the British Museum in London in 1835, at the age of 18. Working alongside influential naturalists such as John George Children (1777-1852), John Edward Gray (1800-1875), and Edward Doubleday (1810-1849), White was mainly involved in identifying, naming and cataloguing arachnids, beetles, insects, and crustaceans. A prolific writer, White published a multitude of books and papers about his zoological findings, with biographer Ann Datta estimating that he produced “more than sixty scientific papers” in the twenty-eight years between 1839 and 1867.[ii] White also wrote on non-scientific matters, and between 1847 and 1851 he spearheaded the campaign for the creation of a National Museum of Scotland, penning many letters to politicians and members of the Edinburgh press.[iii]

Despite working in the Zoological Department for 27 years, White never rose above the position of Zoological Assistant – a snub which his biographers claim was “due to real or imagined difficulties with his superior,” John Edward Grey. Nevertheless, White had an excellent reputation as “an active and effective curator” and was a candidate for various professorial jobs in Edinburgh before and after he retired from the British Museum due to ill health in 1863. Indeed, two years after leaving the British Museum and in the same year as his first visit to Innerpeffray, he printed a pamphlet filled with testimonials for future employers. One of these letters of recommendation was written by no less than Charles Darwin, for whom White had catalogued some of the arachnids collected during his journey on the H.M.S. Beagle. Darwin’s letter, written at his home in Kent on the 26th December 1851, reads:

My Dear Sir,

I have much pleasure in expressing my high opinion of your Zoological attainments; and your great zeal for every branch of Natural History must strike all who are acquainted with you.

Your papers in the scientific journals show how successfully you have worked out original materials. I have often had occasion to visit the working department in the British Museum, and I have invariably found you, permit me to add, most zealous and obliging in your endeavours to aid me in every possible way, and in giving me all the information in your power.

You are at full liberty to show this letter to any one; and I beg to remain, my dear Sir,

Yours sincerely,

Charles Darwin, Esq.

Charles Darwin to Adam White, ‘Letter No. 1466’, 26 December 1851, Darwin Correspondence Project

White did not only correspond with Darwin, and the letter above is just one example of correspondence with notable nineteenth-century figures. In May 1907, O. J. Stevenson wrote an article for The Canadian Magazine, on ‘The Eccentricities of Genius,’ with extracts from a series of letters from White’s archive, then in the possession of a relative in Toronto.[iv] The article reveals that in 1847, White took it on himself to promote a proposed memorial of English poet William Cowper in Westminster Abbey by writing to individuals including Charles Dickens and William Wordsworth to ask for their support. (While Dickens refused “point blank to sympathise with [the] proposal”, Wordsworth was exceedingly supportive and “even offered to increase the amount of his contribution should it be found necessary.”)[v] Stevenson also includes a letter from Wordsworth to White in 1844, wherein Wordsworth agreed to be quoted in a future publication: “I should deem it an honour to have any extracts from my poems inserted in such a book, as I have no doubt yours will prove.”

as featured in ‘The Canadian Magazine’, May 1907, p. 7.

In 1865-66, White wrote letters to both Alfred Tennyson and Coventry Patmore enquiring “as to their opinion of the value of natural history as a subject of the school course”. Patmore’s personal response infers that he had crossed paths with White while they both worked at the British Museum – White having retired a few years prior and Patmore a few weeks away from retiring from his Assistant Librarian position.

British Museum, Dec. 4, 1865.

My Dear White, —I and my children have been delighted with your lucubrations in natural history. I entirely think with you as to the utility of obtaining, if possible, a place for natural history in the ordinary educational course. It is a study of which even a smattering is an advantage. Almost everything one learns concerning our fellow creatures of the field and air increases our friendship for them and our pleasure in their society. Some day you must come and see my bird cage; it contains fifty-four little fellows from all parts of the world, living together on excellent terms.

Yours most truly,

Coventry Patmore.

As featured in O. J. Stevenson, ‘The Eccentricities of Genius’, The Canadian Magazine, May 1907, pp. 7-8.

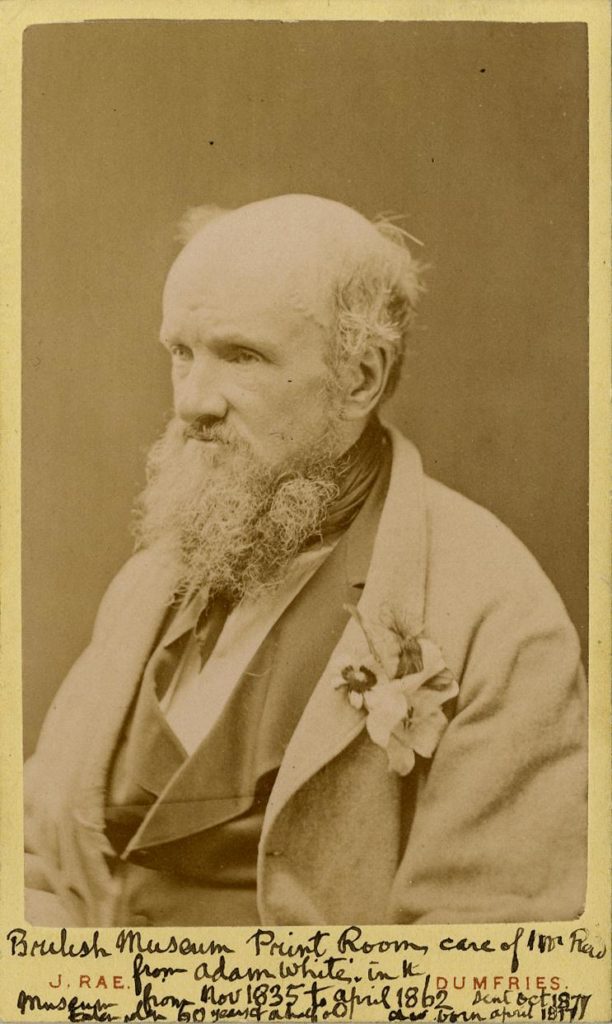

“British Museum Print Room, care of Mr Reid from Adam White, in the Museum from Nov 1835 to April 1862…”

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

When Adam White died in Glasgow on 30th December 1878, he was a highly regarded curator and writer with an admirable scientific reputation. He had authored a library’s worth of papers, articles, and books; enjoyed membership of exclusive groups such as the Linnean Society, the Entomological Society of London, and the Botanical Society of London; had corresponded with men such as Darwin, Dickens, Wordsworth, and Tennyson; and had personally furthered the scientific field of Natural History. Finally, in addition to himself naming numerous species of insects and arachnids, he was appropriately memorialised by John Obadiah Westwood, who named the ‘Taphroderes whitii’ in his honour:

I am indebted to A. White, Esq., the author of numerous valuable papers on Entomological subjects, for directing my attention to this very interesting insect in the Cabinet of the British Museum placed under his charge, and whose name I have much pleasure in associating with so curious a species.

J. O. Westwood, ‘The Cabinet of Oriental Entomology’, (London: William Smith, 1848), p. 32.

If you would like to read more about the Library of Innerpeffray visitors’ books, my first ever published article is now available open access (free to read!) in Studies in Travel Writing: ‘Visitors Visiting Books: visitors’ books at the Library of Innerpeffray’ <https://doi.org/10.1080/13645145.2022.2057387>. I also briefly mentioned Adam White in my first ever PhD blog back in October 2020, which you can find here if you missed it: https://borrowing.stir.ac.uk/visitors-at-innerpeffray-library-j-m-barrie-george-bernard-shaw-and-adam-white/

Isla Macfarlane, PhD Student

[i] ‘Maull’, The British Museum <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG165838> [accessed 28 June 2022].

[ii] Ann Datta, ‘White, Adam (1817-1878), Naturalist’, in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. by H. C. G. Matthew and B. Harrison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

[iii] E. G. Hancock, ‘Adam White’, in The Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century British Scientists, ed. by Bernard Lightman (London: Bloomsbury, 2004), iv, 2147–48.

[iv] O. J. Stevenson, ‘The Eccentricities of Genius’, The Canadian Magazine, May 1907, pp. 1–9.

[v] It appears that White’s appeal was not successful as, although there is a stained glass window in Westminster Abbey commemorating William Cowper, it was “Given by George William Childs, American citizen, 1876” – thirty years after White’s correspondence with prospective sponsors. (‘William Cowper’, Westminster Abbey Commemorations).

Works Cited:

‘Adam White’, The British Museum <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG162220> [accessed 29 June 2022]

Darwin, Charles. Letter to Adam White, ‘Letter No. 1466’, 26 December 1851, Darwin Correspondence Project <https://www.darwinproject.ac.uk/letter/DCP-LETT-1466.xml> [accessed 23 June 2022]

Datta, Ann, ‘White, Adam (1817-1878), Naturalist’, in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. by H. C. G. Matthew and B. Harrison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010) <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/29234> [accessed 22 June 2022]

Hancock, E. G., ‘Adam White’, in The Dictionary of Nineteenth-Century British Scientists, ed. by Bernard Lightman (London: Bloomsbury, 2004), iv, 2147–48

‘Innerpeffray Library Visitors’ Book Volume 1’ (Innerpeffray: Library of Innerpeffray, 1859-1897)

‘Literary and Scientific Portrait Club: Photographs by Maull & Polyblank, circa 1855’, National Portrait Gallery <https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/set/192/Literary+%26+scientific+club+by+Maull+%26+Polyblank> [accessed 29 June 2022]

‘Maull’, The British Museum <https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG165838> [accessed 28 June 2022]

Stevenson, O. J., ‘The Eccentricities of Genius’, The Canadian Magazine, May 1907, 1–9, Toronto Public Library <https://archive.org/details/canadianmagazine29torouoft/> [accessed 29 June 2022]

Westwood, J. O., The Cabinet of Oriental Entomology (London: William Smith, 1848), Biodiversity Heritage Library <https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/34273> [accessed 25 June 2022]

White, Adam, ‘Spiders’, Good Words, March 1866, 212–16, ProQuest British Periodicals <https://www.proquest.com/historical-periodicals/spiders/docview/3300769/se-2?accountid=14755> [accessed 01/02/2021]

‘William Cowper’, Westminster Abbey Commemorations <https://www.westminster-abbey.org/abbey-commemorations/commemorations/william-cowper> [accessed 28 June 2022]

White, Adam, A Popular History of Birds, Comprising a Familiar Account of their Classification and Habits. (London: Lovell Reeve, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, 1855), Wellesley College Library <https://archive.org/details/popularhistoryof00whit_0/> [accessed 27 June 2022]

White, Adam, A Popular History of British Crustacea; Comprising a Familiar Account of Their Classification and Habits (London: Lovell Reeve, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden., 1857), Smithsonian Libraries <https://archive.org/details/popularhistory00whit> [accessed 30 June 2022]

White, Adam, Heads and Tales; or, Anecdotes and Stories of Quadrupeds and Other Beasts, Chiefly Connected with Incidents in the Histories of More or Less Distinguished Men, (London: James Nisbet & Co., 21 Berners Street., 1870), University of California Libraries <https://archive.org/details/headstalesoranec00whitiala> [accessed 30 June 2022]