The collection donated by Janet Burns St Germain never ceases to amaze.

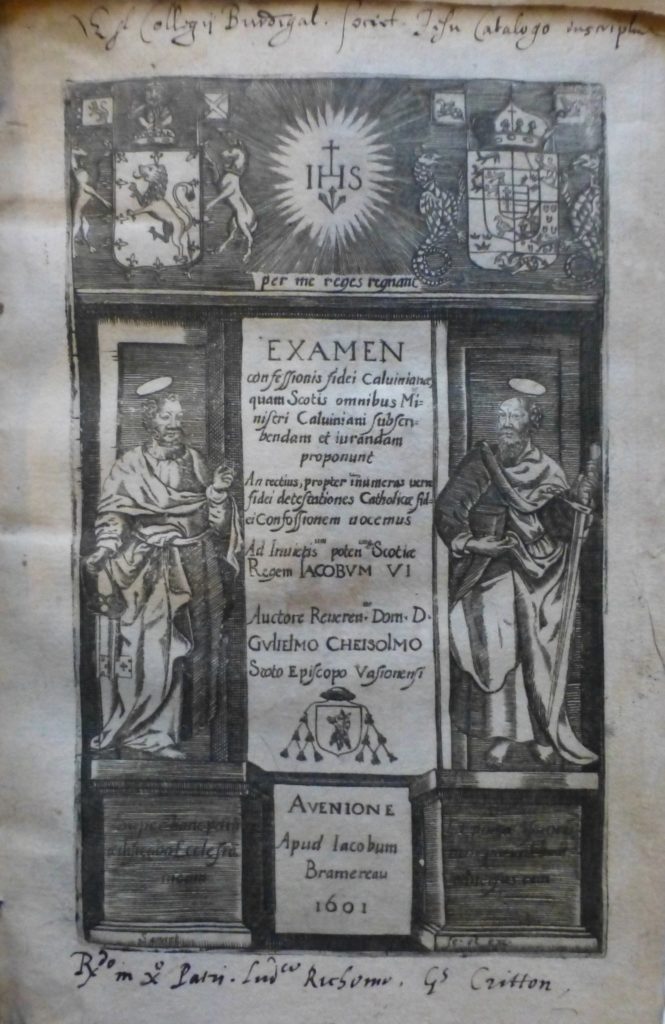

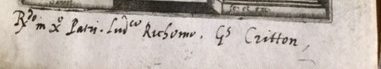

When I examined what is now Library of Innerpeffray LD.4.13, my attention was first drawn to the inscription at the foot of the title: “Rdo in Xo. Patri. Ludvo Richome. Gs Critton”. This copy was donated to Ludovicus Richomus, or Louis Richeome, whom I had come across in another incarnation when working on French Emblem Books. He lived and worked in various places including Lyon, but died in Bordeaux in 1625, which may explain the inscription at the head of the title: “Collegii Burdigal. Societ. Jesu Catalogo inscriptus” indicating that the volume was in the collection of the Jesuit College in Bordeaux. The donor of the book to Richeome was Gulielmus Crittonus, or William Crichton.

However, the author was William Chisholm (ca. 1547-1629; called III, because two others of that name were, in succession, important in Scotland, and more precisely Perthshire), and the book is entitled: Examen confessionis fidei Calvinianae, quam Scotis omnibus ministri Calviniani subscribendam et jurandam proponunt an rectius, propter innumeras verae fidei detestationes Catholicae fidei confessionem vocemus. [Examination of the Calvinist confession of faith which all Calvinist ministers set before all the Scots for them to subsctibe to, or, more properly what we might regard as a confession of faith on account of its innumerable denials of the the true Catholic faith ]. So this is on a controversial topic, but nonetheless dedicated to the King of Scotland, before he succeeded to the English throne. The title also indicates that Chisholm was a Scot, and was the Bishop of Vaison in Provence. Vaison is near Avignon, where the book was published in 1601. His predecessor as Bishop in Vaison was his uncle, also William Chisholm, who was also deeply involved in Scottish affairs, and had earlier been Bishop of Dunblane, in succession to his uncle, yet another William Chisholm. [See DNB.] However, William Chisholm III is of the greatest interest to the Library where this book is now preserved, because he was actually born in Innerpeffray to Jean Drummond and James Chisholm of Cromlix, near Dunblane. He studied in Paris and Rome and became a doctor of theology, before ordination to the priesthood. He joined his uncle in Vaison in 1580, and became bishop on his uncle’s resignation in 1585. He remained concerned with Scottish affairs, and may have been a papal ambassador to Scotland. He died in 1629 in Vaison, and contributions of his to the cathedral building survive, in the shape of two chapels.

What of William Crichton, who gave the volume to Richeome? He was a graduate of St Andrews, and then also studied in Louvain. In September 1562 he was back in Scotland, and present at a meeting between his uncle William Crichton, Bishop of Dunkeld, and the Papal envoy, with whom he returned to Europe; he was ordained around Whitsun 1563, and continued with the rigorous Jesuit noviciate. He was involved in Jesuit colleges in Lyon and Avignon, and was vice-provincial in Lyon in the late 1570s. In 1581 his career changed, and he became a papal adviser on Scottish affairs: the time seemed ripe for a Catholic effort to influence Scotland, and in particular the teen-aged James VI, perhaps given that James’s fiercely protestant tutor George Buchanan died in 1582. The idea was to enlist the help of the Spanish to depose Elizabeth I of England and restore Catholicism to Scotland and England. This came to nothing, because James was nobbled for the protestant cause by the “Ruthven Raid”, and Spain had more pressing matters to hand.

The machinations of 1582, which included a plot to assasinate Elizabeth, came back to haunt Crichton when he was captured while going on a mission to Scotland in 1584, possessed of incriminating papers. He spent time in the Tower of London, but was released when he convinced the authorities that he had advised the plotters against Elizabeth on the grounds that their actions would be completely unlawful. He was in Scotland between 1587 and 1589, during which time he was commissioned, but failed, to contact the Spanish Armada to get the Spanish to invade Scotland during the flight through the North Sea.

Crichton was involved in further machinations in attempts to carry out a pro-Catholic coup in Scotland in 1589-90, but emerges in the Scots seminary in Douai, which moved to Louvain in 1595. He may or may not have been one of the Jesuits present at the Battle of Glenlivet in 1594, when Catholic lords briefly had the upper hand over James and his Protestant supporters.

Crichton was, however, strongly supportive of James in the English succession, which brought him into conflict with English Catholics and other Jesuits who supported the claim of the Catholic Spanish king’s daughter rather than the Protestant King of Scotland. This led to Crichton’s having to leave Louvain (in the Spanish Netherlands) in 1598, when he fundamentally moved to Lyon, where he spent most of the rest of his days, interspersed with some diplomatic activity, and advisory work for the papacy on Scottish affairs. At this point he presumably met Louis Richeome, and eventually gave him Chisholm’s book. However, possibly the most significant move by Crichton in support of James VI brings us neatly back to William Chisholm III. In an attempt to conciliate the Pope and avoid opposition to his succeeding to the English throne, James VI sent Crichton to Rome with a letter dated 4 September 1599, requesting (in the event unsucessfully) that Chisholm be made a Cardinal.

Innerpeffray already had a copy of the French translation of Chisholm’s work: Examen d’une confession de foy (Paris: Jean Gesselin, 1603): its date of acquisition is uncertain, and it appears never to have been borrowed, however appropriate to the background and environment of Innerpeffray.

However, as always with Janet Burns St Germain, we have to ask how much of all this she knew when she bought Chisholm’s book. Serendipity? Flair? Good luck? Skill? Experience, on examining her other books, suggests a combination, which in turn implies something else: landing a copy like this, which links an author, with close Innerpeffray associations, to an early purchaser with an indisputable connection to this author, strongly indicates collecting genius.

[With grateful acknowledgement to Mark Dilworth’s articles on the relevant persons in the DNB; and to Dr Jamie Reid-Baxter.]