As the coronation of King Charles III approaches, books on the shelves of the Library of Innerpeffray have revealed some fascinating details of past coronations in the United Kingdom and Europe. Part of the library’s current exhibition demonstrates that ‘there is nothing new’ in the modern world, that ideas, sayings and practices that seem unique or revolutionary in the present day are often just a reinvention of the past. In some ways the same could be said of the coronations of our country’s sovereigns. As time has passed, some of the arrangements and customs have remained fixed and some have altered, either by legislative changes or by innovation. But the essentials have stayed the same.

For hundreds of years the church and the Christian tradition have been involved at the heart of the coronation service. When the current Archbishop of Canterbury steps forward to crown King Charles III he will be following in the footsteps of his predecessors, following an age old form of words and actions. But the person who preaches the coronation sermon will have the opportunity to do something unique, to deliver a homily which represents present day circumstances and sensibilities to a sovereign who must serve his country in a multicultural world.

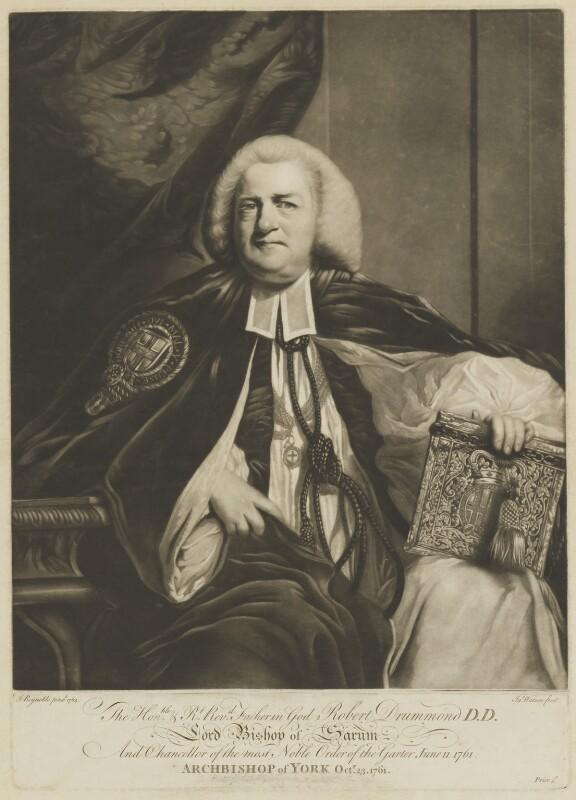

In the past the sermon has only had to reflect a Christian perspective and at the coronation of King George III in September 1761 a Bishop who had a very special connection to the Library of Innerpeffray, Robert Hay Drummond (RHD), delivered it. RHD was the great-nephew of David Drummond, the 3rd Lord Madertie and founder of the Library of Innerpeffray. RHD inherited responsibility for the library and adjoining school in 1739 and did much to augment and extend the book stock. He also raised the funds to build the beautiful neo-classical building in which the library is still housed.

So, how did RHD come to preach the sermon at the coronation of George III? Possibly, as the result of the influence of royal patronage. He had come to the attention of Queen Caroline (the wife of George II) whilst he was acting in a play at Westminster School and some years after she influenced his appointment, at the relatively young age of 25, to the royal chaplaincy. She remained his patroness for the rest of her life. RHD accompanied George II whilst the king was on campaign in Europe and preached a sermon for him.

He continued to advance within the church spending time in the bishoprics of St.Asaph and Sarum (Salisbury.) In 1761, whilst he was the Archbishop-elect for York, he was chosen to preach the coronation sermon.

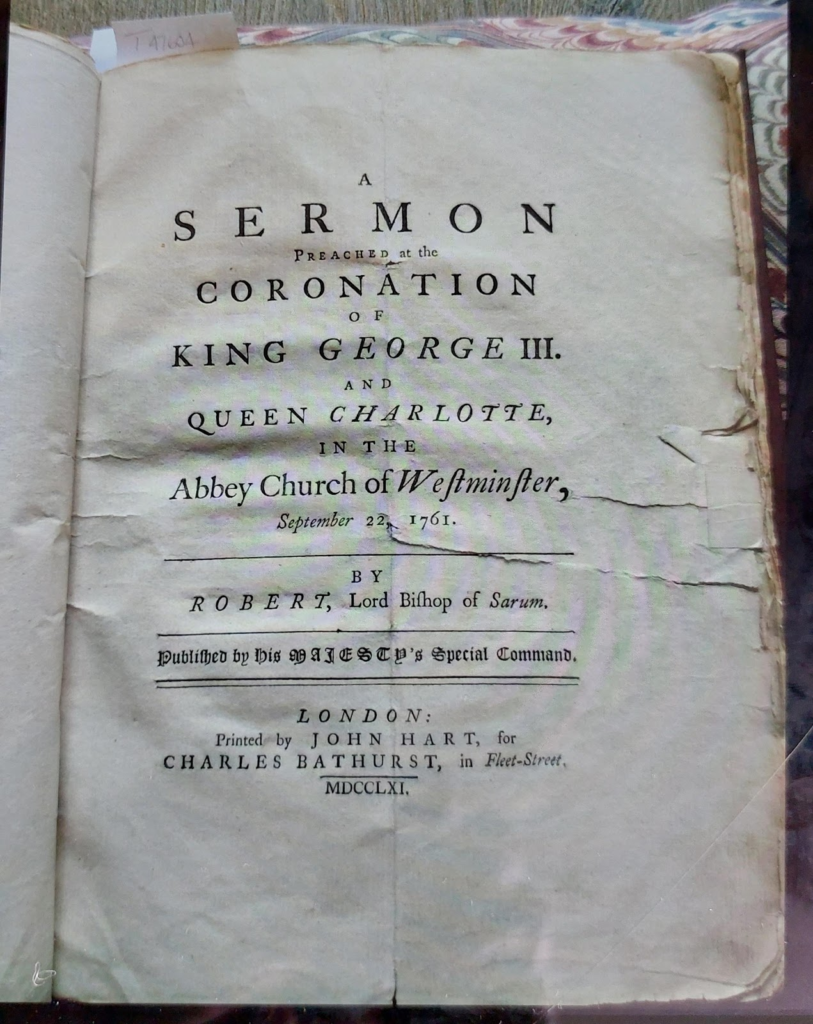

He chose an Old Testament verse (I Kings, X.9) as the basis of the sermon – ‘because the Lord loved Israel for ever, therefore made he thee king, to do justice and judgement.’ The sermon was described as being ‘sensible and spirited and free from fulsome panegyric’, dignified in style and delivered in well-chosen language. In reading the sermon it is very clear that RHD presented his advice to the king in two main arguments that he described as truths: –

- ‘That when great and good kings reign, they are the means by which God blesses his people,’ and

- ‘That the duty and the end of royalty is to do justice and judgement.’

The sermon uses other biblical texts to illustrate his arguments and he sets out various ideas on how the sovereign can lead by example; influence society for the common good, peace and happiness; be mindful of the people’s affection for the previous monarch and his achievements; accept any personal suffering he may face in the course of his duty and service to the country and utilise general knowledge and science as well as religion in reaching his decisions. If he followed these directions, RHD opined, the country would be blessed with citizens who had a respect for the law and who showed a ‘cheerful obedience’ to government. RHD also exhorted the people to be loyal and supportive of the new king in the pursuit of ‘pure religion’, virtue, just government and liberty. Regardless of individual belief or religious practise, some readers might consider that the sermon would produce a good template for life today and it is possible to see many facets of the reign of the late Queen Elizabeth II through this lens. Once again, some aspects of life change very little over time.

Some time after the coronation in 1761 the King ordered that the sermon should be published and the Library of Innerpeffray holds a copy of it in a book of RHD’s sermons. The following image is taken from that book.

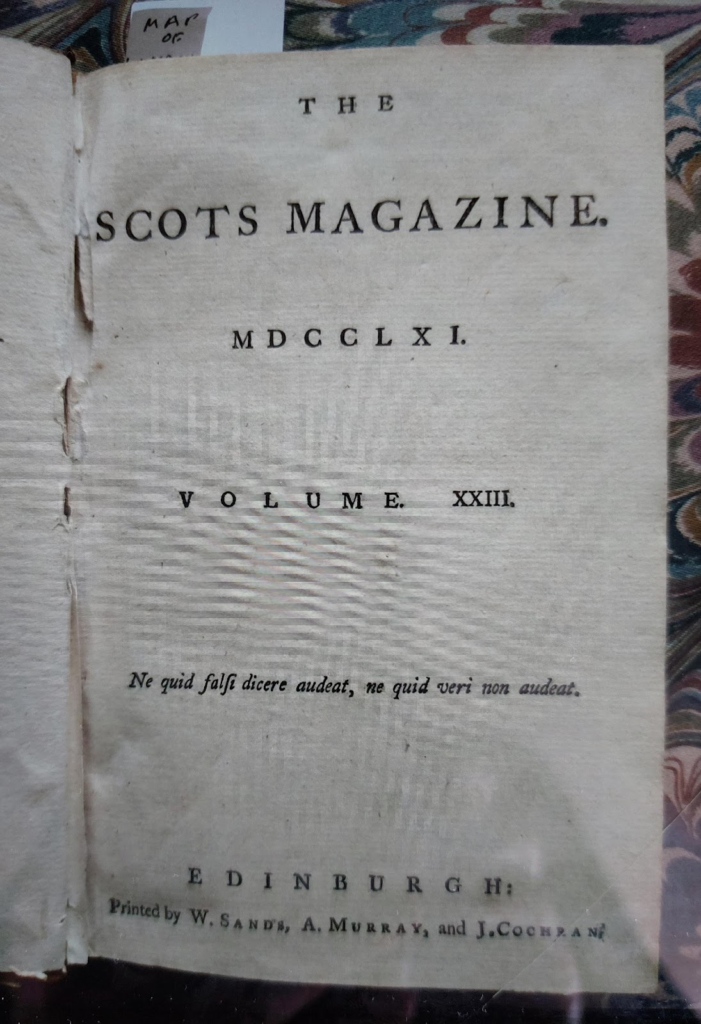

A second book in the library, a compendium of The Scots Magazine, gives a detailed account of the coronation of George III and Queen Charlotte, which took place only two weeks after their marriage. The account mentions the role of RHD and describes a very long day –starting at 9am and finishing after 10pm – which was marred by mishaps and a very prolonged, tiring ceremony. It is reported that one of the jewels fell out of the King’s crown during the day and that it was found after the coronation banquet; but there is no actual evidence of this. Even the weather was covered – a letter reprinted from the London Chronicle of 29 September 1761 tells us that the weather leading up to and following the coronation day was wet and stormy, but the day itself enjoyed ‘…an extraordinary alteration in the weather.’

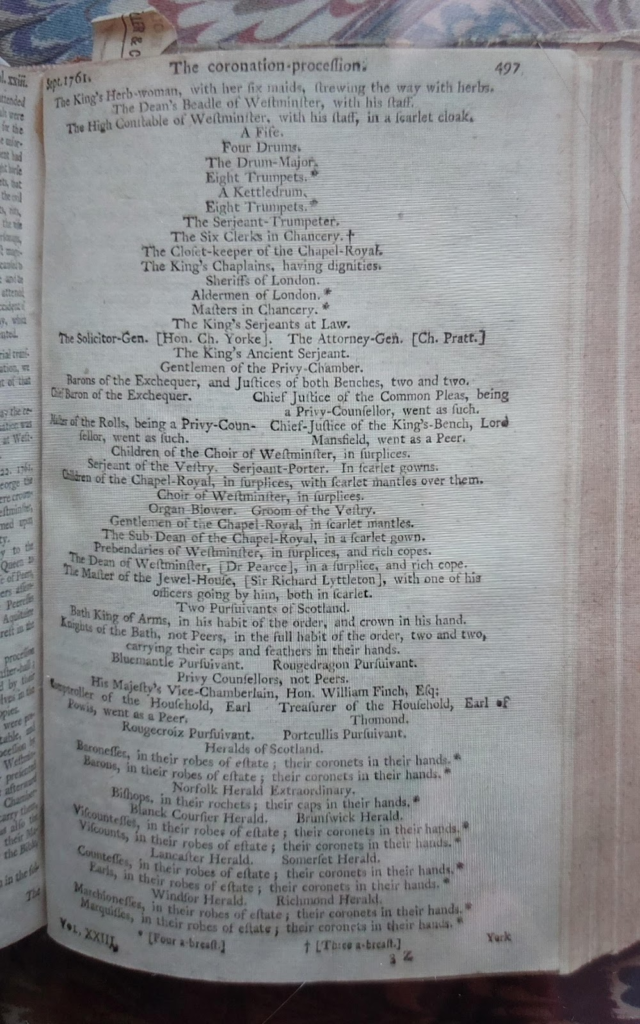

But perhaps the most interesting part of the article is a detailed description of the procession from Westminster Hall to Westminster Abbey. The participants were lined up in order and walked to the Abbey, preceded by a herb woman and six maids who scattered herbs on the route ahead of the walkers. The participants were numerous and varied and included Peers and Peeresses of the realm, soldiers, choristers, clerks, masters of the king’s wardrobe and jewels, privy counsellors, knights, heralds, barons and baronesses, aldermen, aristocrats, clergy, sheriffs, senior legal staff, members of the King’s and Queen’s personal staff, senior government officials and the Archbishop of Canterbury. Quite a gathering of the great and the good and the writer describes it as a procession that ‘…far excelled any thing of the kind ever known in this kingdom, or any other part of the world, for grandeur and magnificence…’

Once inside the Abbey the lengthy coronation service began and the article gives a detailed account, outlining the order of service, the participants, the regalia used, the clothing, the chairs of Estate used by the monarch and his consort and the music performed by musicians and choristers. As a piece of reportage it is clear and interesting and gives the reader a real understanding of the proceedings.

The following photograph shows an extract from the article about the order of the procession. This represents only a proportion of the people who took part- there is another page and a half of detail.

In reading these books and other accounts it has become clear that many similarities exist between the coronations of the distant and recent past. The UK is the only country in Europe still to carry out a formal coronation of the monarch and his consort and with over a thousand years of history of coronations, in four very different nations, it is perhaps surprising that so many elements of the event are familiar to us today. As has already been said, there is not much in life today that is really new; we are not in uncharted territory where coronations are concerned.

Examples of continuing customs are:

- The coronation oath– this is the only legal requirement in the proceedings and it has been amended over the centuries to reflect the changes in our society such as the roles of different churches, the political union of kingdoms, the creation of The Commonwealth etc. But essentially the oath remains a promise to govern according to the laws and customs of all citizens.

- The use of Westminster Abbey – the venue has been used since 1066 (initially only in England) and the upcoming coronation will be the fortieth to be held there.

- The Procession – the monarch makes a public procession from his/her place of residence to the abbey. These days the monarch travels by coach rather than on foot but the eye-catching and colourful pageantry remains.

- Regalia – the orb, sceptre, coronation ring and St. Edward’s crown are still used.

- The Stone of Destiny forms part of the structure of the throne. This year it will travel from its home in Edinburgh Castle to London for the ceremony but will then return to Scotland.

- Holy Oil is used to anoint the monarch using a spoon that has been part of the coronation regalia (in England) for hundreds of years. It survived the destruction of religious artefacts by Oliver Cromwell, though St. Edward’s crown did not. That is a replica.

- Music – this forms a centrepiece of the ceremony and new pieces are often commissioned (eight by George III, twelve by Charles III.) Some pieces are a fixture eg Handel’s composition for Zadok the Priest.

- Homage is paid to the new sovereign by attendees, though the numbers included in this part of the ceremony vary.

- A Court of Claims (now called the Coronation Claims Office) is set up to allow people to apply for official roles in the coronation.

- Crowds – the streets are filled with spectators and the abbey is crowded with invited guests and officials. Galleries have been built in the streets, in the abbey and in Westminster Hall in the past to accommodate huge numbers of spectators, guests and participants.

- Public celebrations – military guns are fired, street parties are held, recipes are created (Coronation Chicken, Coronation Quiche), fireworks and/or bonfires are lit.

- Re–enactments – these days the coronation is replayed on TV and streamed all over the world to allow public involvement in the event whereas in the past plays and re-enactments took place to allow people outside of London to get a flavour of what had happened in the capital.

- The State pays for a state occasion. The budget for George III’s coronation was initially estimated to be £9,430 but it has been reported as actually costing anywhere up to £70,000. Overspends in public life reverberate all through history!

So wherever you are on coronation day look out for innovations. They are not always numerous and you will be observing history in the making. Interesting accounts of the coronations of the past remain in books, diaries, print newspapers and journals in libraries and archives all over the world. Indeed we have copies of The Tatler, Picture Post and The Field at Innerpeffray that document royal events of the 20th century, including the coronation of the late Queen. But we live in a digital, fast-changing world and it will be interesting for today’s younger generations to see how much of the coverage of this year’s coronation actually survives.

And finally…….

Footnotes.

- What happened to Robert Hay Drummond after the coronation of George III? He served for many years as Archbishop of York and undertook renovations of his palace and the parish church of York. He was a hospitable man, a friend to many and a liberal patron of the arts. He became Lord High Almoner to George III and reformed many abuses of that office whilst also taking part in the proceedings of the House of Lords where he influenced political power as a Whig. Policy changes against the Whigs occurred during the reign of George III and this led RHD to cease attending the House of Lords. He then devoted himself entirely to his archdiocese and the education of his children, particularly with respect to the teaching of history and the love of reading, encouraging a wide range of books. His wife Henrietta (whom he had married in 1749) died in 1773 and RHD never really recovered from the blow, passing away himself in 1776.

- Music played for George III. The 1761 coronation is the only one known where one composer, William Boyce, created almost all of the music. He composed eight new anthems but refused to compose a new setting for Zadok the Priest. He petitioned the king to allow Handel’s original composition to be used and the king agreed. Handel’s wonderful piece has been used ever since. Three full rehearsals of the coronation music took place before the event and tickets to these rehearsals were sold to the public. The scope of the music demanded a huge cast of musicians and choristers, so much so that alterations had to be made to the layout of the abbey and an assistant conductor appointed so that everyone could actually follow the conductor’s instructions.

- The Scots Magazine claims to be the oldest magazine in the world that is still being published. Whether or not that is the case, it is certainly one of the world’s best selling Scottish interest magazines. It was first published in 1739 and has had some breaks in publication during its existence. It has been published continuously since 1927 under a series of owners, the current owner being DC Thomson & Co Ltd, the publisher of various famous comics (The Beano, Dandy, The Broons etc) and newspapers and owner of several media sites. One of its most famous editors from 1759-65 was William Smellie, who was the joint founder of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, a friend of Robert Burns and the editor of the first edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Charles Bathurst (cited on the title page of RHD’s printed coronation sermon) was a London bookseller. He started his working life as an apprentice printer and worked for Benjamin Motte, whose bookselling and publishing business operated from Middle Temple Gate, Fleet Street, London. Motte published work by Jonathan Swift, initially anonymously at the author’s request and notably Gulliver’s Travels in 1726. Later on, Bathurst and Motte collaborated on other works and printed another book written by Swift, A Complete Collection of Genteel and Ingenious Conversation.

If this has whetted your appetite to look at and/or read some of the treasures held in The Library of Innerpeffray, please take a look at our website which contains details of our collections and opening times for visitors.

Some of the collection can only be viewed by prior appointment with The Keeper of Books, Lara Haggerty, so please do check in advance if there is something in particular that you would like to see. We are no longer a lending library, so unfortunately you cannot borrow books.

SW

Sources.

www.commonslibrary.parliament.uk

Dictionary of National Biography

The British Library

The National Portrait Gallery

Exeter Working Papers in the British Book Trade History: the London Book Trade 1735-75, via

Records of London’s Livery Companies online

Wikipedia