Innerpeffray may have been conceived as a lending library all those centuries ago by David Drummond, third Lord Madertie, but this purpose has expanded over the intervening years to the wonderful resource we have today. One of the more recent uses is as a reference library, and it is thanks to this that this blogpost was conceived. As well as my role as a volunteer guide at the Library, I am a Process Safety Engineer and part of this job entails raising awareness of previous industrial incidents to identify where things went wrong and how we in the industry can reduce the likelihood of similar events happening in the future. Typically, these hark back to events from, at most, thirty or forty years ago – easily within living memory. For a change, however, I decided to use the Library to see if there were records of industrial accidents going back not just decades, but centuries. My search was successful…

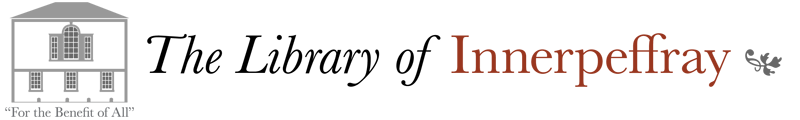

The first incident I came across was an account of a colliery explosion by Dr. Arthur Charlett, who was the Master of University College, Oxford, from 1692 to 1722. This was included within the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, the oldest science journal in the world. The account describes an incident at Fatfield Colliery, which is situated just to the south of Newcastle on the River Wear. On 18th August 1708, at around 3am, there was, to quote Dr. Charlett, “The sudden Eruption of a violent Fire”. As you can see from the text above, he goes into great and vivid detail of the impact of the colliery explosion and the extents of the blast damage. He goes on to describe some of the different dangerous gases that might be encountered whilst mining – the “Stith” and the “Sulphur” – and the effects of each. For modern day readers, the “stith” is an asphyxiant and would most likely consist of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide and the “Sulphur” refers to methane with some residual sulphur components to give the smell. Given the explosion, it is more likely that the build-up in this case was the “Sulphur” – if you think of damage caused by gas explosions in people’s homes today, it is easy to understand the deadly impact of a build-up of methane.

What was particularly fascinating for me from a professional viewpoint was that he does not just describe the event and the background, but does on to actually theorise the sequence of events that led to the issue. The second page of the account (shown above) describes the workings of the mine. The production of “Stith” and “Sulphur” are pretty much unavoidable when mining, certainly in 1708, and, as such, methods have to be found to keep the concentration of these gases at acceptable levels. Today, mines use complicated ventilation systems with fans to ensure that they keep levels down, but in 1708, they were solely reliant on good natural airflow – “a free Communication of Air”, as Dr. Charlett put it. Where this was hard to achieve, by some combination of the mine’s layout and the still atmospheric conditions, workers were removed from the danger zone; a decision that I as a 21st Century Process Safety Engineer very much applaud! Whilst the danger zone was unmanned, however, the noxious and explosive gases were still very much being released. As such, when the wind picked up again, the flammable “Sulphur” was then pushed through the mine until it reached the candle of an Overman. This provided sufficient energy to ignite the flammable cloud, which, through the confinement of the mine’s tunnels, then exploded, killing the men who had returned to work in the mistaken belief that the danger had passed with the increased air flow.

It would be lovely to say that the 69 people who lost their lives that August morning were the last to suffer from a colliery explosion of this kind. Sadly, there were a further three explosions at the same colliery in the next 120 years. Few, if any, changes were made on the back of this incident – the workforce being considered very much expendable and the hazards an unavoidable part of the very profitable mining industry. It took over 100 years for improvements to be made to lighting in mines, with various safety lamps being developed after the Felling Colliery disaster in 1812, the most notable being that of Sir Humphrey Davy.

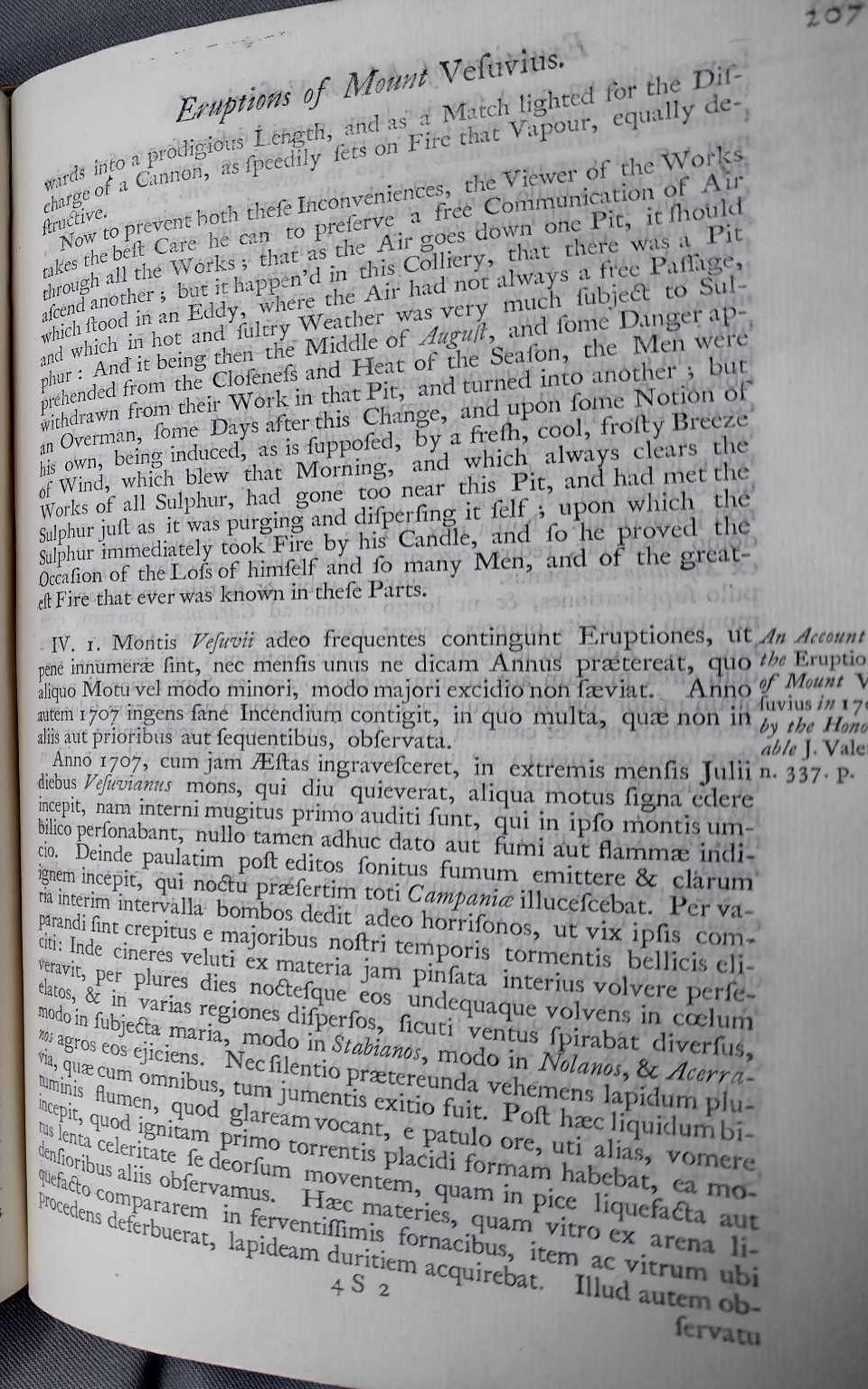

The second incident that I investigated through the Library’s tomes occurred in Brescia, Italy, in August 1769 (coincidentally 61 years to the day after Fatfield). I came across this in the September edition of the Scots Magazine – the world’s oldest magazine still in publication! The Library holds the first 45 years of the Magazine from 1739 to 1784 and these are particularly popular for Culloden and the Declaration of Independence. It also includes various news articles from around the world, not just those directly affecting Great Britain, hence the inclusion of an account of a magazine of gunpowder exploding after the church in which it was stored was hit by lightning.

As you can see from the text above, the impact was colossal – “it overturned about a sixth-part of the houses in the town, and… buried near 3000 persons under their ruins”; “All the streets are covered with ruins of every sort”; “A cannon of twenty-five hundred weight [1.3 tonnes] carried two miles and a half”.

Unlike the Fatfield colliery incident, this account is entirely descriptive, with little heed given to an explanation of what actually happened. It is, however, responsible for the long held belief that over 3000 people died. In fact, more reliable accounts published a few years after the disaster concluded that the maximum death toll was 400-800 people – still an astonishing number, but significantly less than 3000. It is perhaps unsurprising that this account does not delve too deeply into the explanation of what happened that day – after all, it was fairly simple! Lightning struck the church where the gunpowder was stored and the spark ignited the highly flammable powder. The confines of the vaults in which it was being stored ensured that that the church acted effectively like a bomb and so caused it to explode. Given lightning strikes are still a known hazard today, I was ready to leave this incident here, but a little more digging led me down some interesting further routes…

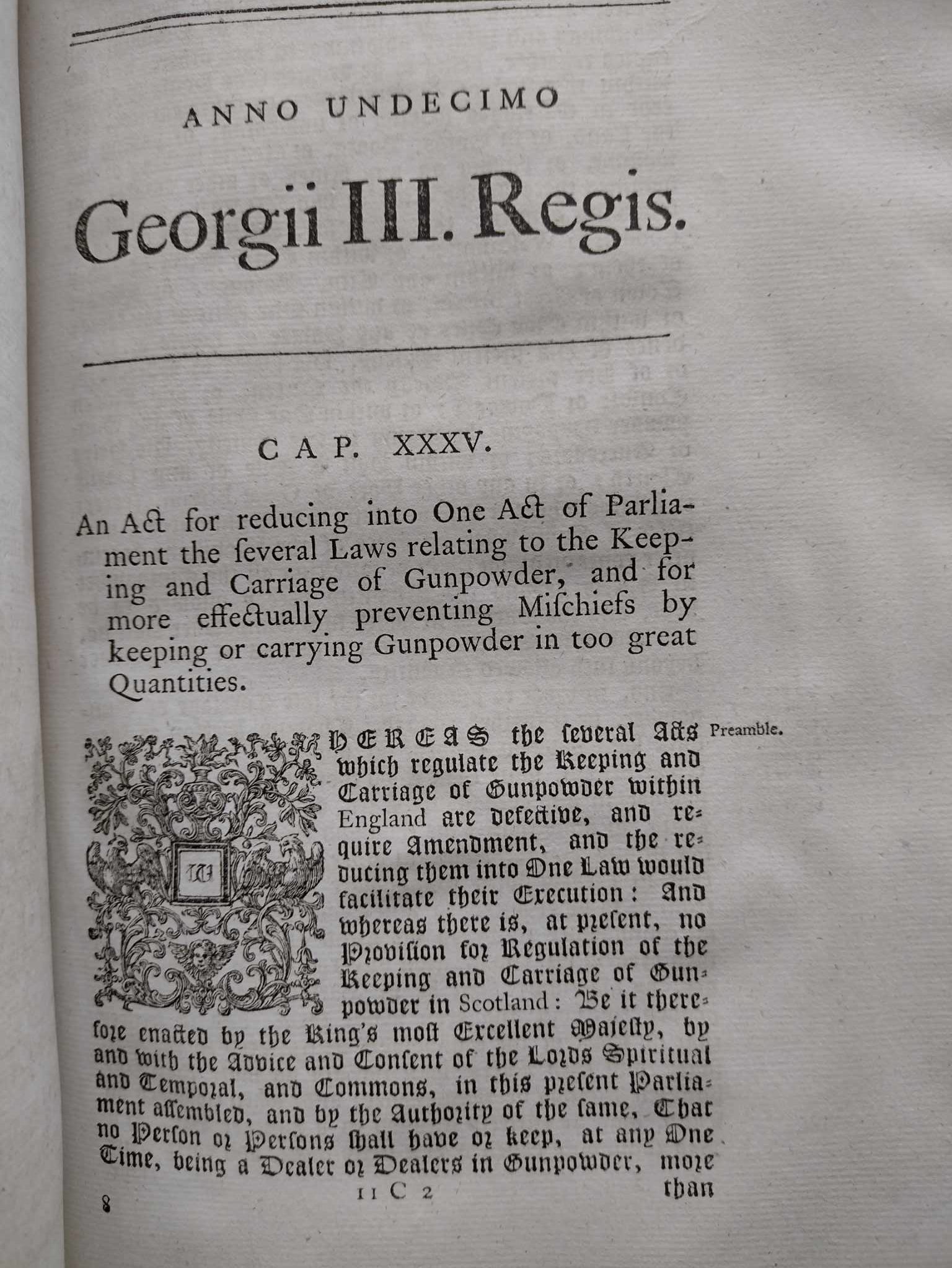

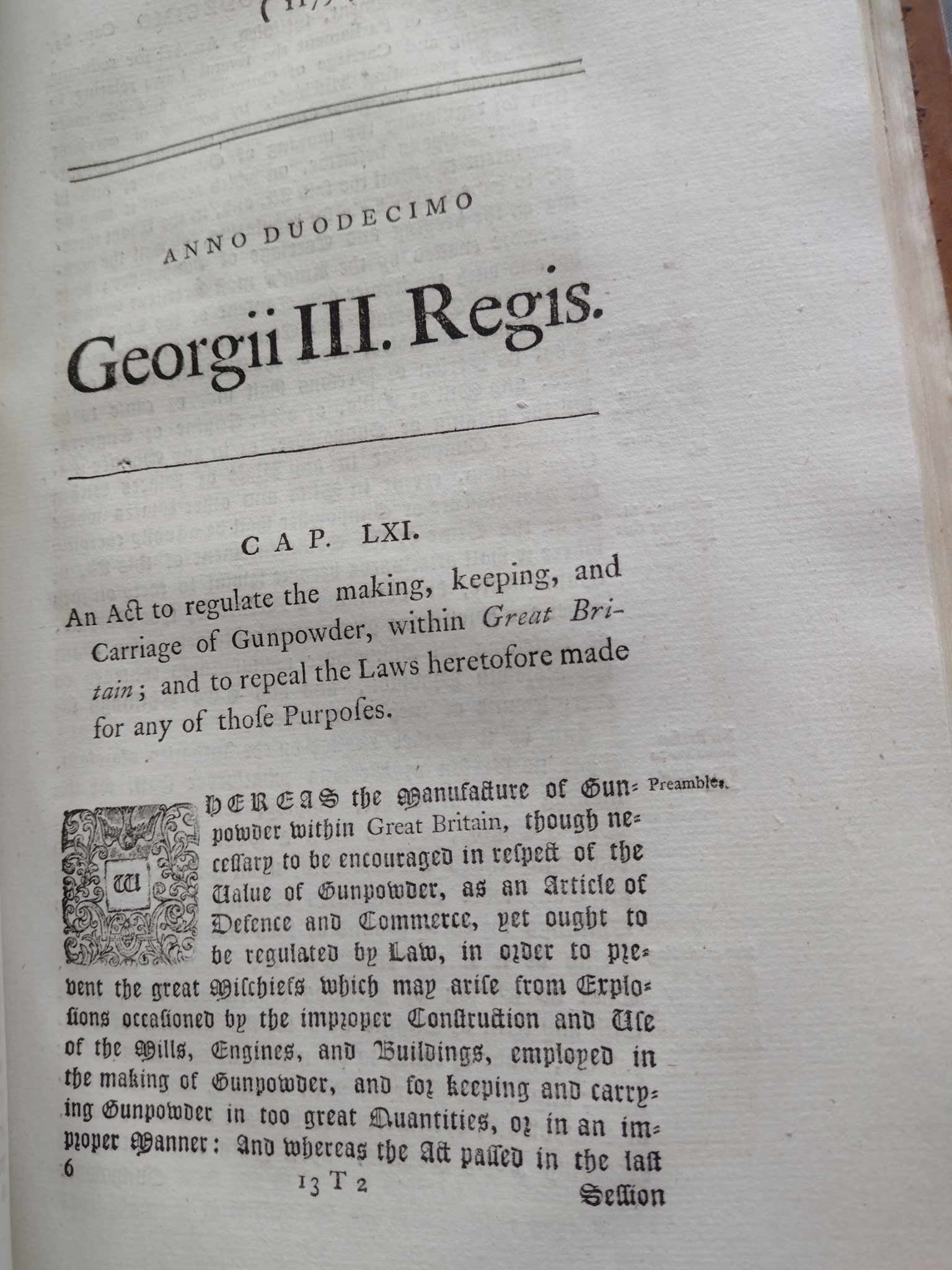

More recent online accounts mentioned that the Brescia incident led to legal changes in Great Britain in 1770 and 1772. Fortunately, the Library has a few shelves filled with tomes of Statute Books from the reign of George III, so, for the first time, I dived into these and found them both:

On the left, we have the original act from 1770, which was their first attempt at properly regulating the amount of gunpowder that could be held in one place, and the follow-up from 1772 when they realised that they had forgotten to regulate the actual manufacture of gunpowder (a brilliant quote from the full text of the Act reads “the Act passed in the last session contains no Provision for regulating the making of Gunpowder, and is in other Respects defective”). Both acts set out maximum quantities that could be held, which reduced in close proximity to towns and cities, as well as how much could be conveyed at once. The 1772 Act also added in regulations around who could manufacture gunpowder, as well as limiting the amount of charcoal that could be stored adjacent to gunpowder. Whilst neither Act directly references Brescia, it is clear from the content that the recent incident was foremost in the minds of those crafting these new laws, a hypothesis further strengthened with our final piece of evidence from the Library and the appearance of a man whom I think you’ll know.

Benjamin Franklin is rightly lauded for a life incredibly well lived, with his political, diplomatic and scientific achievements all very well documented. At the Library, we have a six volume set of the Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin and within the final volume, there is a letter outlining his recommendations for the improvements to the lightning protection that should be made to the Royal Magazine at Purfleet, which had been built in 1764. Within this letter, shown below, he refers to the incident at Brescia to highlight the necessity of protecting gunpowder magazines from the dangers of a lightning strike. He describes a number of measures that he suggests should be put in place to ensure the security of the gunpowder magazine, as well as referring to experimental work carried out not just in the UK, but also in the colonies only a few short years before the Declaration of Independence was signed.

So to conclude, there are lessons to be learned from the past that still have direct relevance to us today. There was a colliery explosion in Turkey in October 2022 that killed at least 42 people due to a methane explosion and a lightning bolt struck a fuel oil storage tank in Cuba in August 2022, killing 17 firefighters. The lessons learned from history through the deaths of hundreds people are still so easily forgotten today; what other stories lie buried within the volumes on the shelves of Innerpeffray Library?

RS