During the winter months, when the library is closed to the public, there is still a lot of work to be done on the collections. The appropriate storage and care of books is an important part of the library’s work and our volunteers are kept busy with the dusting of the books, checking their shelf positions against the catalogue, identifying necessary repairs to covers and/or pages and cleaning the bookcases. It is an important exercise which is for the most part routine. But it does offer the chance for volunteers to get to know the collections more closely and to study books of particular interest to them. And, from time to time, we rediscover a book that throws a light on events in the modern world through the lens of history.

One such book was discovered shortly after the Supreme Court’s judgement on whether a second referendum on independence could be held in Scotland under legislation passed by the Scottish Parliament. The Court ruled against the arguments made by the Scottish government and, in doing so, brought the public and media spotlight back onto the nature of the Union and the matters that are reserved in law for determination by the UK Parliament. So when the small, nondescript slim brown volume was first taken off the shelf for cleaning little did we know that it would be so topical and pertinent to the current debate.

The book may be small in physical size (smaller than a typical modern paperback,) relatively short at 156 pages, but it is a first edition, has a long and impressive title, a celebrity author and is signed by a famous person. It also forms part of a very important collection of books (the Scotland Collection) which was gifted to the library in 2013 by a wealthy American bibliophile, Janet Burns St.Germain.

The following photographs show the front cover, the spine and the impressive title page.

Several points of interest can be seen from the title page:

- The text is about an inquiry into the reasonableness and consequences of a Union with Scotland

- The book was printed and sold in Paternoster Row in London in 1706 by a ‘publisher’ named Benjamin Bragg. So it was published in the year in which the Treaty of Union was ratified.

- The name of the author is not included on the title page, but as can be seen from the handwritten note on the opposite page, the author has been identified as William Paterson, a co-founder of the Bank of England.

- An outline description of the contents of the book has been set out, including a proposed scheme for the Union of the two countries (note that only Scotland is mentioned on the title page, England is not) and a discussion of the relative financial, legal and other ‘facts of moment’.

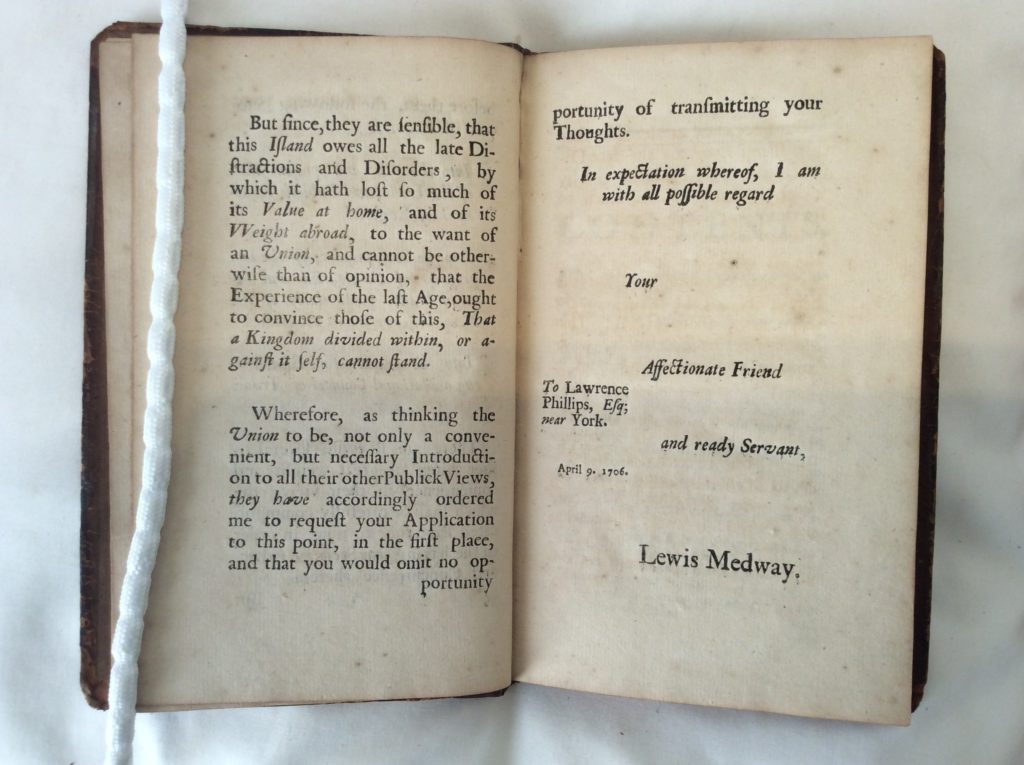

So, we now know what the book is about and we know the identity of the author but why is William Paterson not identified on the title page? Well, the text is written in the form of a report on the proceedings of and discussions amongst the members of an imaginary club named the ‘Wednesdays Club in Friday Street.’ There is a dedication written under the pseudonym of Lewis Medway, addressed to Laurence Philips, Esq near York and the text that follows is an important attempt to explain the economic consequences of a proposed Union between Scotland and England. The club members discuss various topics about the proposed Union and Lewis Medway

provides a record of the meeting plus an account of individuals’ opinions and observations.

It can be seen from the dedication that Paterson was very much in favour of the Union, arguing that the loss of the countries’ standing in the world and their economic problems was owing to ‘the want of a Union.’ Indeed he states, as a further argument, that ‘..a Kingdom divided within, or against itself, cannot stand.’ His argument throughout the text could be summarised as being that the introduction of a Union was not only convenient but a necessity and that all arguments against it could be weighed and measured against the positive ones and found wanting.

The book was written at a time when the crowns of Scotland and England had long been unified but their Parliaments, of course, had not. Various pieces of legislation passed in England and the failure of the Darien Scheme (which Paterson had helped to devise) in the late 17th century had affected both trade (particularly with the Dutch) and thus the economy of Scotland. In addition the two countries had different ideas about the nature of the Succession to the crown and this problem needed to be resolved since Queen Anne had no living heir. It made sense to many of the nobility and political classes, therefore, to unite the two Parliaments though, in Scotland at least, the opinion of everyday folk was at odds with their world view.

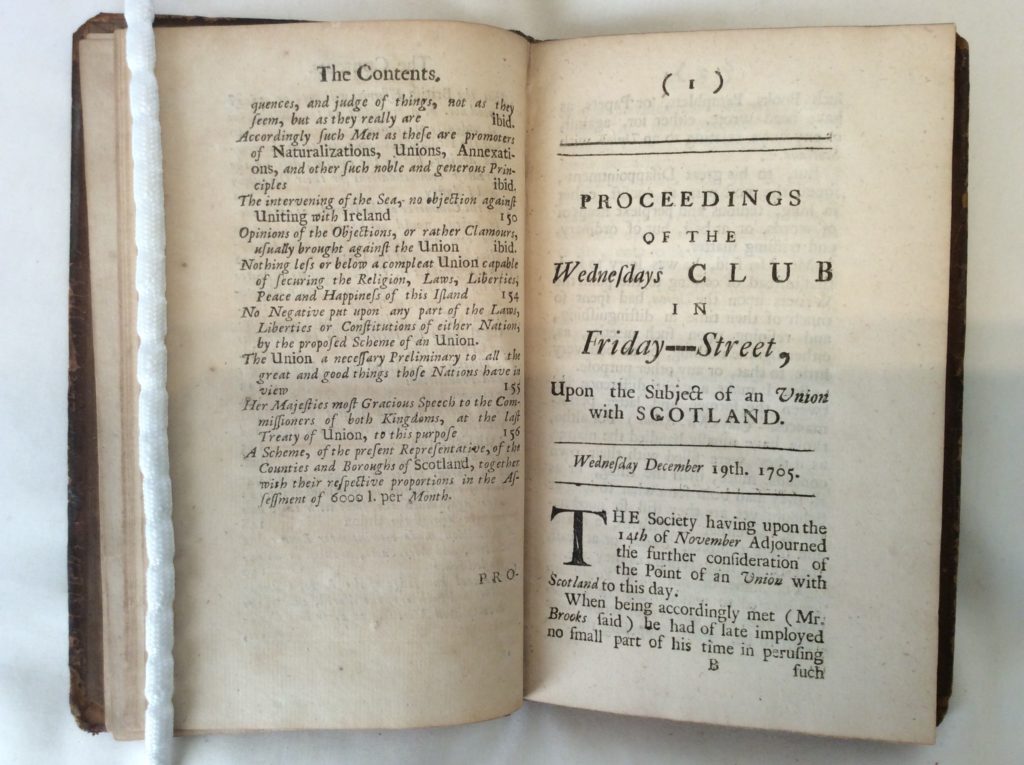

On reading the details of the contents page it can be seen that many of the arguments of 1706 are still being discussed in the media and Parliament today. For instance, the advantages/disadvantages of the Union to both countries; the amount of representation Scotland should have within the unified Parliament; the effects of a united economy on the relationship with European countries; the need for common granary and fisheries policy; ports of entry to the country; the relationship with the island of Ireland; the effects of restraints and prohibitions of trade on the economy and of course the discussions on taxation, debts and revenues, customs and excise, government expenses, coinage, weights and measures and poor relief (benefits, in today’s language.) Does this all sound familiar?

The final four pages contain information on a proposed scheme for the representation of Scotland in the unified Parliament, setting out numbers of representatives and taxation per Shire, Borough and city.

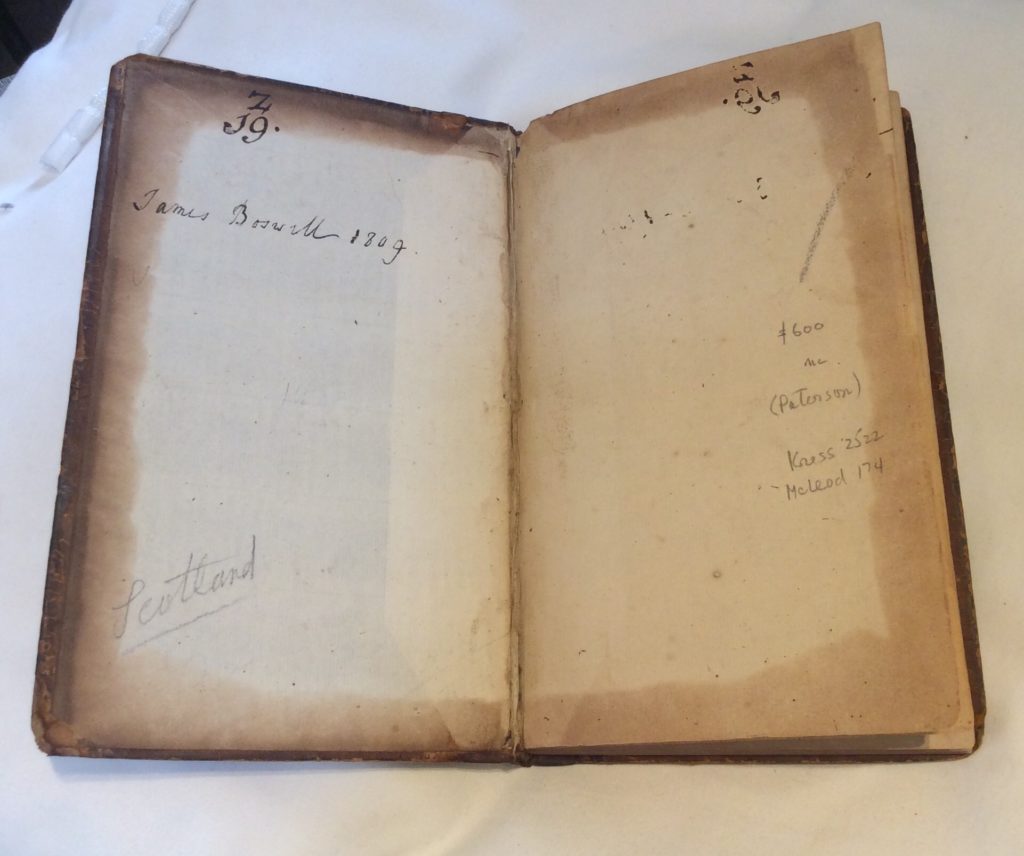

And what of the signature of the famous person? Well that belongs to James Boswell the younger (1775 -1822) and it can be found near the beginning of the book with a date of 1809 beside it. Boswell was the second surviving son of the more famous James Boswell, the lawyer and biographer of Samuel Johnson, a biography which is considered to be among the finest in the English language. The younger Boswell was also a lawyer and he rose to become Commissioner of Bankrupts. He was also the literary executor of Edmond Malone, a Shakespeare scholar and a friend of the elder Boswell.

End notes.

In carrying out some background research for this post, a number of interesting facts surrounding people and places relating to the book came to my attention and I thought that they might be of interest to some readers.

- William Paterson ( 1658 – 1719) was a Scottish trader and banker, co-founder of the Bank of England and one of the main proponents of the catastrophic and commercially disastrous Darien Scheme. In early life he emigrated to the West Indies where he gained considerable business acumen as a merchant. He was also reported as having had dealings with local buccaneers. He first conceived the Darien scheme whilst living in the West Indies and perceived it as a trading colony in Panama for Scotland to gain economic advantage in establishing trade links with the Far East. On returning to London in 1687 he made a fortune with the Merchant Taylors’ Company, through foreign trade, perhaps primarily through the slave trade in the West Indies. In 1691 he published a pamphlet, A Brief Account of the Intended Bank of England. He became a director of the bank in 1694 but left his position in 1695 after disagreements with colleagues. In 1698 he travelled to Panama with his family to join the Darien expedition. His wife and child died and he became very ill himself. On returning to Scotland in 1699 he became active in his support for the pro-Union movement.

- Benjamin Bragg was a bookseller by trade, sometimes known as a trade publisher. In the times that he was operating, the term publisher meant something entirely different to what we know today. A publisher could commission a book to be printed but he/she could also be involved in the wholesale and/or retail book trade. He was involved in the production of many books and pamphlets but some of his publications were seemingly dubious in terms of how and when they appeared on the market. He fell foul of the Court of the Stationers’ Company (see notes below) and appears in their court records more than once; for example, in November 1706 his name appears in relation to the selling of sham almanacks.

- The printing trade was controlled as a monopoly from 1557 by a livery company known as the Stationers’ Company (SC). The SC was also responsible for policing the industry and also controlled as a monopoly a joint stock company called The English Stock which had sole control of the publishing of almanacks, psalters, school books, ABCs and catechisms. It was this monopoly which Benjamin Bragg offended against in 1706 (see above.)

- Copyright Law. In 1695 the Licensing Act was allowed to lapse and this produced a situation where anyone with enough capital and access to a press could set themselves up as a publisher. This led to an explosion in piracy in the printing trade and the whole subject of who owned copyright in the printed word was brought into sharp focus. In 1704 the novelist and poet Daniel Defoe wrote an essay on the regulation of the press in which he argued for a free press but with the introduction of some statutory protections to give authors the rights to their own work and to prevent piracy. Benjamin Bragg seems to have been involved in piracy; in 1706 he published a pirated, error-filled edition of Defoe’s ‘Jure Divino’ one day before the official version was due to appear. In 1706 the bookseller trade also argued for a change in the law, to protect publishers and authors. In 1707 a group of thirteen influential City of London publisher/booksellers (not including Bragg) introduced a petition to parliament on the subject of copyright. All of this eventually led, in 1710, to the Statute of Anne which was effectively the first legislation on copyright.

- Paternoster Row was situated in the St.Pauls Churchyard area of the City of London until it was devastated by aerial bombing during in World War II. In 2003 it was replaced by Paternoster Square. In the 12th century it was the centre of production of paternoster beads by skilled artisans. These beads were used by illiterate monks and friars to help them keep track of the progress of their required daily recitations of Our Father (Pater noster) prayers. The road is said to have received its name from the habit of monks and clergy leaving St Pauls Cathedral and processing along the road chanting the litany, including the Pater noster prayer. Nearby streets, Ave Maria Lane and Amen Corner also received their names from these processions. By the time Benjamin Bragg was operating out of the Black Raven, Paternoster Row was the centre of London’s bookseller trade, with the different bookseller properties being advertised by signs rather than numbers.

- The Black Raven was taken over in 1710/11 by a lady named Sarah Popping who was a bookseller, printer and publisher. She published, among many other things, a newspaper named The Observator which was associated with Daniel Defoe. She also published works which are attributed to Defoe. In 1711 she was imprisoned for libel and in 1712 she was taken into custody accused of printing, against the order giving printing rights to someone else, a report on the trial of the Earl of Winton for treason. She was released however after claiming no knowledge of how her name had been connected to the publication!

- Janet Burns St. Germain was American by birth but was of Scottish ancestry. She had a lifelong interest in Scotland, its history and culture and she amassed a sizeable collection of rare Scottish books, most of them first editions. She donated them to The Library of Innerpeffray from 2013 onwards, intending them to be seen and read. Some of the Library’s greatest treasures are contained within this Scottish Collection. Janet died in 2016.

And finally, if this has whetted your appetite to look at and/or read some of the treasures held in The Library of Innerpeffray we look forward to welcoming you: opening times for visitors can be found here. This book: An Inquiry into the Reasonableness and Consequences of an Union with Scotland, London, 1706 will be on display in 2023 as part of our ‘Nothing New’ exhibition.

Some of the collection can only be viewed by prior appointment with The Keeper of Books, Lara Haggerty, so please do check in advance if there is something in particular that you would like to see. We are no longer a lending library, so unfortunately you cannot borrow books.

Please note that we are currently closed for the winter and will reopen on 1 March 2023.

-SW