Welcome to the fourth in this series of blogs that have been appearing throughout the year to interest, intrigue and, one hopes, entertain followers of the goings-on of Innerpeffray Library. The theme is a general one, but should deliver up something to pique everyone’s interest at some point. For those of you lucky enough to have visited the Library, you will have noticed that the shelves really do go from floor to ceiling and, as a result, there are some shelves that really do not get the attention that they perhaps deserve. This series aims to remedy this injustice by dragging out the ladder and going for a quick Tour of the Tops to see what gems there are awaiting true recognition! This ‘Episode’ looks at ‘orrible deaths and mysterious going-ons throughout English history, discovers the somewhat wilder side of our most famous playwright and has a wander through the stars with a slightly pedantic writer of marginalia!

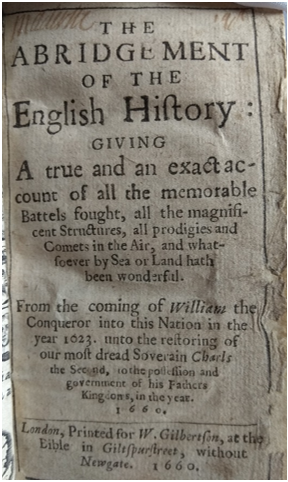

To change things up somewhat from previous ‘Episodes’, I am going to start with not just one book, but two! They are quite similar in theme and approach, so make a good pairing and I found them fairly close together as well. The first book is “The Abridgement of the English History”, published in 1660 and it is what we call a “Madertie book” as it was owned by the Founder of the Library, David Drummond, third Lord Madertie, as you can tell by the signature in the top left corner. The quality of the research for the book can be guessed at on the front cover – you will note that William the Conqueror is said to have come “into this Nation in the year 1023”, which would have been a great shock to William, given it was twelve years before he was born. I mean, he undoubtedly was a bit of a child prodigy, but there are limits!

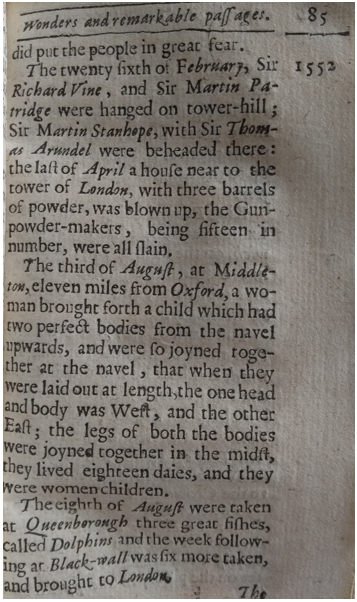

The book reads a bit like a tabloid history of England, with a strong focus on ‘orrible deaths, fantastic goings-on and such, rather than great affairs of state, or major events in other countries at the time. The page on the left gives a good example of the things that the author considered essential reading for his target market, with executions, industrial accidents, conjoined twins and unusual finds from the sea all making an appearance in the text. Of course, 1552 was an otherwise quiet year… No need to discuss the rise of John Dudley to the Dukedom of Northumberland, from which he launched what was effectively a coup d’état the following year on the death of Edward VI. And who really cares about the imposition of the Protestant Book of Common Prayer when you can read about the hanging of Sir Richard Vine and Sir Martin Patridge? Truly this was the tabloid history book of its day!

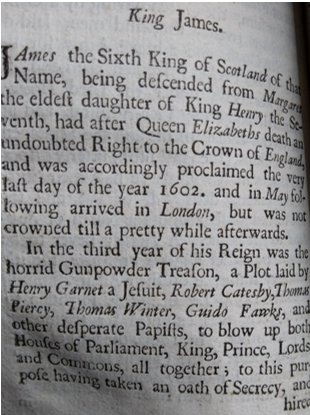

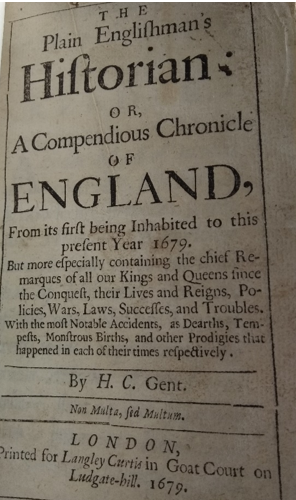

The book with which I have paired it is in a similar vein, although admittedly a little less focused on the sensationalist side of history, whatever it says on the front cover! “The Plain Englishman’s Historian” dates from 1679 and manages to keep the spotlight on significant events a little bit more than the “Abridgement” does, although the dates are not always those that one learns at school! Let’s take a couple of examples. The first one (below left) covers the death of Queen Elizabeth I, and also features a guest appearance by one the best-known villains in English history. You will note that Queen Elizabeth is said to have died “on the very last day of the year 1602”. “But wait!” I hear you cry “She died on March 24th 1603! How can that be the very last day of the year 1602?”. Well, that’s because the year used to be reckoned from March 25th (Lady Day) and not 1st January as we do now. This all changed as part of the move from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar in 1752 (this move involved ‘missing’ 11 days that year and is the reason why the tax year starts in early April – it is eleven days after the old New Year’s Day). So here the date is correct for a book published in 1679, even though it looks somewhat odd to a modern reader!

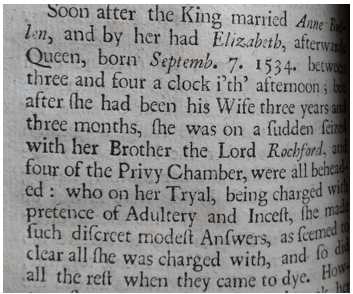

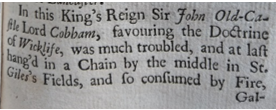

The second example (above) is from the beginning of Elizabeth’s life – the very beginning in fact! Again, the year is one out from that learned today, although this time it is a year later than the normally given 1533! This time I wonder if it is just a printer’s error – one assumes that the threes and fours were fairly close and perhaps it was just a little mistake when putting the print together – but it is possible that it was a vague attempt at disguising the fact that Elizabeth was conceived out of wedlock, given her parents married in January 1533 and she was born in the September. Given Elizabeth’s high favourability even 75 years after her death, her parents’ marriage was a tricky topic to cover – as you can imagine when the husband orders the execution of the wife… As a final note, serving as a nice linking piece between these books and our next, I leave you with a mention of a certain Sir John Oldcastle, Lord Cobbam (see left). He was a follower of the heretical teachings of Wycliffe – a Lollard – and as such was executed in 1417. However, his friendship with a young Henry V forms a major part of the works of a chap who crops up in our next book…

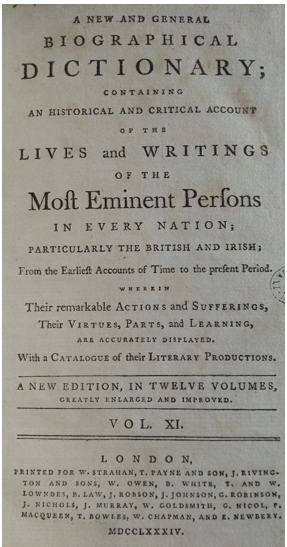

And so we move onto the next book – “A new and general Biographical Dictionary”, published in 1784. Faced with such a selection of books (it was a twelve-volume set!), I decided to settle for looking up someone I knew would be therein: Mr. William Shakespeare! I am quite the fan of the bard’s plays, and one of my favourite books in the Library is a Hollinshed’s History, used as the source material for Macbeth. Given this book was written over 160 years after Shakespeare’s death, it’s far from a first hand account of his life, but it does shed some light on one the least known periods of his life. From the birth of his twins in 1585 until references to him in London in 1592 (including Robert Greene’s description of him as an “upstart crow”), Shakespeare disappears from the historical record for seven years. All sorts of theories abound – he became a soldier, he went travelling (especially to Italy), he was a husband in Stratford – but the Biographical Dictionary has a different idea. This theory is one that still does the rounds from time to time, although the form does vary sometimes. Here though, it is categorically clear. Shakespeare robbed the deer park of a local landowner multiple times and, as such, was prosecuted. He responded as any guilty poacher would (!) and wrote a hate-filled ballad about the landowner. This so inflamed the situation that he was forced to leave the county for his own safety and as such he ran away to London where he fell in with the players due to his “wit and humour”. It is a really intriguing account, and one wonders if there were any records available at the time to corroborate this story. It seems to have originated with Shakespeare’s first biographer, Nicholas Rowe, in the early 18th Century. I don’t suppose we shall ever know the events that drove a Warwickshire wool merchant’s son to leave his hometown and seek his fortune in London with the players, but I do quite enjoy this suggestion! Before I close out this section, I should add that Sir John Oldcastle from the previous book was the inspiration for Sir John Falstaff in Shakespeare’s Henry IV and Henry V plays, as well as The Merry Wives of Windsor. Originally called Sir John Oldcastle, the Lord Cobham of the time objected to his ancestor being used in such a fashion and so the name was changed to avoid trouble.

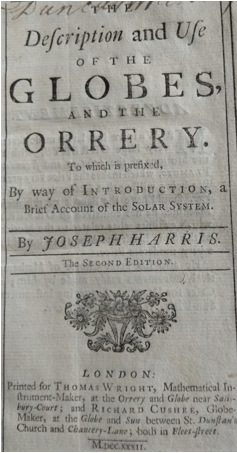

Today’s final book is one I chose simply because of its subject – a word that is just a delight to enunciate at any opportunity – the orrery! What’s an orrery? Well, it’s one of these…

An orrery!

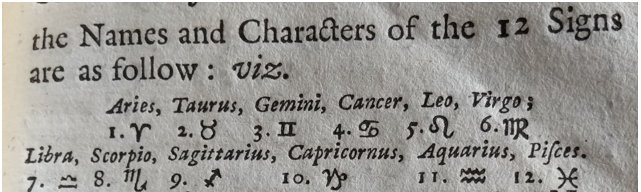

Isn’t it just gorgeous? A scale model of the solar system with the planets shown in their relative positions to one another! The book itself is called “The Description and Use of the Globes and the Orrery” and it dates from 1732. The book has a lot of information about the solar system as it was understood in the 18th century, with a diagram showing the orbits of the planets (I make no apology for not including it here as the orrery is a far better drawing!). A few things jumped out at me as I read through the book. Firstly, there were a number of strange symbols cropping up throughout the text. I was a little unsure as to what they meant – were these an unusual form of printer’s marks? Page 45 had the answer: They were symbols for the signs of the Zodiac, as you can see below:

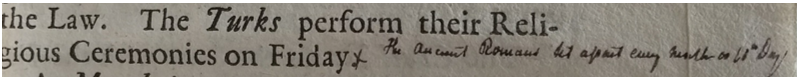

These are, of course, very similar to the signs still used today – so please pardon my ignorance! In addition, there was an interesting piece of marginalia on the page where I first spotted the zodiacal symbols that ties in nicely with one of our previous books. It is a reference to the dates of the equinoxes and the author refers to these as happening “(according to our way of reckoning) about the 10th of March and 12th of September”. At the side there is noted “O.S = to 20th March to 22nd Sept.”. Clearly someone was reviewing this post-1752 and wanted to ensure the book was brought somewhat up to date. Our mysterious marginalian (suggestions for a better term for someone who writes marginalia are welcomed!!) has further comments throughout the book, often adding further detail to the author’s work, such as the one below.

So ends the fourth ‘episode’ of the Tour of the Tops with an overly enthusiastic marginaliographer (is this a better term?) updating his book on globes and orreries! I hope that you have enjoyed this varied selection of books from the hardest to reach shelves of Innerpeffray! As the Library is now open once again, I do encourage you all to come by and visit when you can so you can perhaps explore these incredible books for yourself. The next ‘episode’ will take a look at foreign food, a sycophantic dedication with a strong Innerpeffray connection and a slightly inaccurate essay on tobacco. Hopefully this will have whetted your appetite for the next Tour of the Tops, coming to the blog soon!